According to a detailed article by Jeremy Scahill in the Nation, that is precisely what happened in Yemen on February 2, 2011. The innocent journalist is Abdulelah Haider Shaye; the President of Yemen at the time was Ali Abdullah Saleh; and the foreign leader who convinced Saleh not to pardon Shaye is none other than Barack Obama, President of the United States.

Shaye, 35, is a highly respected investigative journalist of the type that is always in short supply: one who takes the time to get the facts for himself and to report them, letting the chips fall where they may. He is not content simply to rehash government press releases; but though he has interviewed many al-Qaeda figures, he does not repeat what they say uncritically either. He abhors the criminal tactics of both terrorists and state functionaries and exposes them.

Shaye is “very open-minded and rejects extremism,” his best friend, dissident Yemeni political cartoonist Kamal Sharaf, told Scahill. “He was against violence and the killing of innocents in the name of Islam. He was also against killing innocent Muslims with pretext of fighting terrorism. In his opinion, the war on terror should have been fought culturally, not militarily. He believes using violence will create more violence and encourage the spread of more extremist currents in the region.”

The U.S. government says Shaye was “facilitating” the work of al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), though it refuses to present any evidence to back up its assertion. Shaye is related by marriage to the radical Islamic cleric Abdul Majid al Zindani, the founder of Imam University whom the U.S. government has deemed a terrorist. Shaye has used this relationship and other connections to gain access to al-Qaeda leaders not because he sympathizes with them but simply to get a good story — and sometimes to expose them for the criminals that they are.

For instance, notes Scahill:

As the U.S. ratcheted up its efforts to assassinate the radical cleric Anwar Awlaki, among the charges leveled against him was that he praised the actions of the alleged Fort Hood shooter, Maj. Nidal Hasan. A key source for those statements was an interview with Awlaki conducted by Shaye broadcast on Al Jazeera in December 2009. Far from coming off as sympathetic, Shaye’s interview was objective and seemed aimed at actually getting answers. Among the questions he asked Awlaki: How can you agree with what Nidal did as he betrayed his American nation? Why did you bless the acts of Nidal Hasan? Do you have any connection with the incident directly? Shaye also confronted Awlaki with inconsistencies from Awlaki’s previous interviews. If anything, Shaye’s interviews with Awlaki provided the U.S. intelligence community and the politicians and pro-assassination punditry with ammunition to support their campaign to kill Awlaki. (Awlaki was killed in a U.S. drone strike on September 30, 2011.)

“It is difficult to overestimate the importance of his work,” Gregory Johnsen, a Yemen scholar at Princeton University who had communicated regularly with Shaye since 2008, told Scahill. “Without Shaye’s reports and interviews we would know much less about Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula than we do, and if one believes, as I do, that knowledge of the enemy is important to constructing a strategy to defeat them, then his arrest and continued detention has left a hole in our knowledge that has yet to be filled.”

Johnsen suggested that Shaye’s seemingly easy access to AQAP figures that the U.S. and Yemeni governments could not find was one reason they were determined to silence him. It seems unlikely, however, that this alone was sufficient to get him sent up the river. What got Shaye’s name on the short list for the slammer was his exposé of what really happened in the Yemeni village of al Majala on December 17, 2009. On that date, writes Scahill,

The Yemeni government announced that it had conducted a series of strikes against an Al Qaeda training camp in the village of al Majala in Yemen’s southern Abyan province, killing a number of Al Qaeda militants. As the story spread across the world, Shaye traveled to al Majala. What he discovered were the remnants of Tomahawk cruise missiles and cluster bombs, neither of which are in the Yemeni military’s arsenal. He photographed the missile parts, some of them bearing the label “Made in the USA,” and distributed the photos to international media outlets. He revealed that among the victims of the strike were women, children and the elderly. To be exact, fourteen women and twenty-one children were killed. Whether anyone actually active in Al Qaeda was killed remains hotly contested. After conducting his own investigation, Shaye determined that it was a U.S. strike. The Pentagon would not comment on the strike and the Yemeni government repeatedly denied U.S. involvement. But Shaye was later vindicated when Wikileaks released a U.S. diplomatic cable that featured Yemeni officials joking about how they lied to their own parliament about the U.S. role, while President Saleh assured Gen. David Petraeus that his government would continue to lie and say “the bombs are ours, not yours.”

In short, Shaye had shown the Saleh and Obama administrations for their roles in a duplicitous and monstrous act. Clearly, such impudence could not be permitted to go unpunished.

“Abdulelah was threatened many times over the phone by the Political Security and then he was kidnapped for the first time, beaten and investigated over his statements and analysis on the Majala bombing and the U.S. war against terrorism in Yemen,” Abdulrahman Barman, Shaye’s attorney, told Scahill. “I believe he was arrested upon a request from the U.S.”

Shaye was arrested a second time, beaten, and “disappeared” into solitary confinement for 34 days. He was eventually tried by a sham state security court and “convicted of terrorism-related charges and sentenced to five years in prison, followed by two years of restricted movement and government surveillance,” according to Scahill.

His conviction and sentencing caused a huge uproar among the Yemeni populace. “Some prominent Yemenis and tribal sheikhs visited the president to mediate in the issue and the president agreed to release and pardon him,” Barman told Scahill. “We were waiting for the release of the pardon — it was printed out and prepared in a file for the president to sign and announce the next day.”

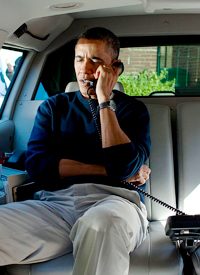

Unfortunately, word leaked out to the press, and the next thing Saleh knew, Obama was on the other end of the telephone line, “express[ing] concern over the release of” Shaye, according to a White House summary of the call, because of his “association with AQAP.” And that was the end of Shaye’s pardon.

It seems safe to assume that Saleh would not have considered pardoning Shaye if he really believed Shaye was a terrorist or terrorist facilitator. He must have known that Shaye’s conviction was bogus and that the resulting unrest among the people was far more threatening to him than Shaye’s reporting ever was. Obama, however, had no reason to fear a Yemeni uprising; but he did have reason to fear more revealing stories from Shaye. Saleh obviously knew on which side his bread was buttered and caved in to pressure from Obama.

Thus it was that on Groundhog Day 2011, President Obama saw the shadow of bad public relations and made the call that ensured that instead of an early spring, Shaye would spend five more years in the cooler.