There is likely no historical record of a population drowning in alphabet soup, but nations in the 21st century appear to be working on it. Just as in baseball where you “can’t tell the players without a scorecard,” you might need a glossary to follow negotiations of free trade agreements.

By now, perhaps, most Americans know that NAFTA stands for the North American Free Trade Agreement, a trade pact purportedly passed to reduce and eliminate trade barriers among the United States, Canada, and Mexico enacted in 1993. Then came another round of negotiations on the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, and GATT begat the World Trade Organization (WTO), the international authority that rules on allegations of violations of trade agreements.

NAFTA begat CAFTA, or the Central American Free Trade Agreement. Also in the works is a General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS). If you weren’t following trade agreements closely, you might have missed the TRIP (Trade-Related Intellectual Property) and TRIMS (Trade-Related Investments) accords. Then there is the TPP (Trans-Pacific Partnership) and the TTIP, which is the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership for increasing commercial ties between the United States and the nations of the European Union. The United States and EU have already established an HLWGJG, or High Level Working Group on Jobs and Growth, to find ways to increase cross-Atlantic trade and investment.

Giving the President Trade Power

But perhaps the most important initials for the United States, and for Congress in particular, are TPA. A campaign is under way for Congress to renew Trade Promotion Authority that requires “fast-track” approval or rejection of any trade agreement negotiated by the executive branch. In fast-track legislation, debate on an agreement is limited, and Congress may vote the pact up or down, but may not adopt or even offer amendments to the agreement.

The reason for this is obvious. Negotiating all of the provisions of a trade agreement is a long, drawn-out process, requiring concessions on all sides. None of the participants wants to see hard-won concessions in negotiations subject to alteration or repeal by amendments in Congress that would likely require a reopening of negotiations. Trading partners may be reluctant to negotiate an agreement without the assurance of a straight “up or down” vote when the package is presented to the people’s representatives in Congress.

Opponents argue, however, that the authority is an unconstitutional usurpation of the legislative powers of Congress. The Constitution, after all, stipulates, in the very first sentence of the very first article: “All legislative powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States.” (Article I, Section 1)

It says nothing about suspension or abdication of that power. Further, the Constitution assigns to Congress the power “To regulate Commerce with foreign Nations.” (Article I, Section 8)

There is in constitutional law a principal known as “the nondelegation doctrine,” which, the Supreme Court has held, limits the ability of Congress to delegate its legislative authority to what is required by “common sense and the necessities of the government co-ordination.” (J.W. Hampton Jr. & Co. v. United States, 1928) The doctrine was upheld in the court’s 1998 decision in Clinton et al. v. City of New York, when the justices, in a 6-3 decision, rejected as unconstitutional the Line-item Veto Act of 1996. By authorizing the president to veto portions of tax and spending bills, the court ruled, the law violated both the non-delegation doctrine and the “presentment” clauses of the Constitution (Article I, Section 7), according to which Congress presents legislation to the president, who may sign (or let become law without his signature) or veto the entire bill. Though not dealing with Trade Promotion Authority, the logic of the court’s decision suggests TPA has it backward: Congress may approve and/or amend a proposed trade agreement and the president may, with his signature or veto, vote it “up or down” (subject to congressional override by a two-thirds vote in each house in the case of a veto).

Using Congress’ Creation

Congress nonetheless created the fast-track authority in the Trade Act of 1974, with the authority due to expire in 1980. It was extended for eight years, however, by a 1979 act of Congress and renewed again in 1988 through 1993. It was later extended a number of times by congressional actions, including a 3:30 a.m. House approval of the Trade Act of 2002 on June 27 of that year. It expired on July 1, 2007, albeit with fast-track authority continued for any trade agreements negotiated before that date, including agreements negotiated with Panama, Colombia, and South Korea.

The Obama administration indicated early this year that renewal of the authority would be a requirement for the successful conclusion of the Trans-Pacific Partnership negotiations, involving 11 nations. The proposed trans-Atlantic agreement with the European Union would be even bigger, creating what has been described as the world’s largest free trade zone.

“If Obama could negotiate and implement just these two agreements,” wrote Paul Sracic in The Atlantic, “he would almost without question be the most successful trade president in U.S. history.” But gaining renewal of fast-track, or Trade Promotion Authority, for passage of those agreements will not be easy, as there will be resistance in Congress to trading the legislative power of a sovereign nation for the promise of future prosperity. As with trade agreements in general, opposition to fast -track cuts across partisan and ideological lines. Democrat Max Baucus of Montana is a leading proponent of renewal in the Senate, where fellow Democrat Sherrod Brown of Ohio, concerned over the loss of manufacturing jobs in the nation’s “rust belt,” is opposed to giving the president that authority without stricter enforcement of existing trade rules, increased spending on job training for displaced workers, and action against China over currency manipulation. In the House, a coalition of progressive Democrats, representing the concerns of organized labor, and Tea Party Republicans reluctant to cede Congress’ constitutional authority to the president, may succeed in blocking passage.

Trade agreements affect the economic future of some 300 million Americans. Limiting congressional debate will surely limit the public’s and even the representatives’ and senators’ knowledge of aspects of trade agreements that typically cover thousands of pages. In a June 13, 2013 letter to U.S. Trade Representative Michael Froman, Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) expressed her concern over what she described as “a lack of transparency” in the negotiations for the Trans-Pacific Partnership.

“I have heard the argument that transparency would undermine the administration’s policy to complete the trade agreement because public opposition would be significant,” the senator wrote. “This argument is exactly backwards. If transparency would lead to widespread opposition to a trade agreement, then that trade agreement should not be the policy of the United States.”

As Alexander Hamilton is said to have put it more succinctly, “Here, sir, the people rule.” And the people rule through their elected representatives, as Hamilton noted when showing the House of Representatives chamber in what was then the new Capitol building to a visitor from England. (Whether the autocratic Hamilton approved of the people’s rule is another question.) By abandoning the right to a full debate and to amend trade agreements, Congress would be surrendering to the executive branch not only its own but, by extension, the people’s power under the Constitution of the United States.

If President Obama wants to establish a free trade legacy, wrote Sracic, he must face the reality that “the toughest trade negotiators he will face are not in Tokyo or Brussels, but on Capitol Hill.”

As the Founders intended and the Constitution requires.

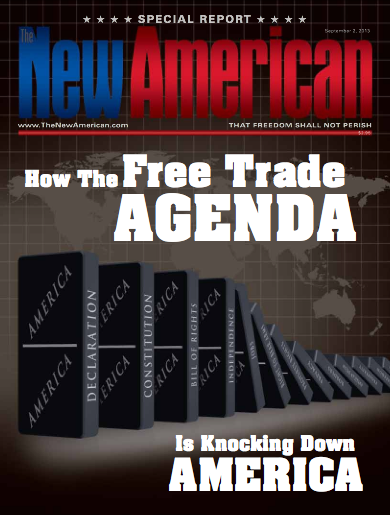

The above article is part of our special report “How the Free Trade Agenda Is Knocking Down America.” This report warns that the free trade agenda is a dangerous and deceptive bait and switch. The intent is not to create genuine free trade but to transfer economic and political power to regional arrangements on the road to global governance. Because of what is at stake, we encourage you to read the entire special report (click here for the PDF) and to become involved.

The above article is part of our special report “How the Free Trade Agenda Is Knocking Down America.” This report warns that the free trade agenda is a dangerous and deceptive bait and switch. The intent is not to create genuine free trade but to transfer economic and political power to regional arrangements on the road to global governance. Because of what is at stake, we encourage you to read the entire special report (click here for the PDF) and to become involved.