Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Director John Brennan recently made a startling but little-noticed admission: A belligerent foreign policy can actually make the United States less safe.

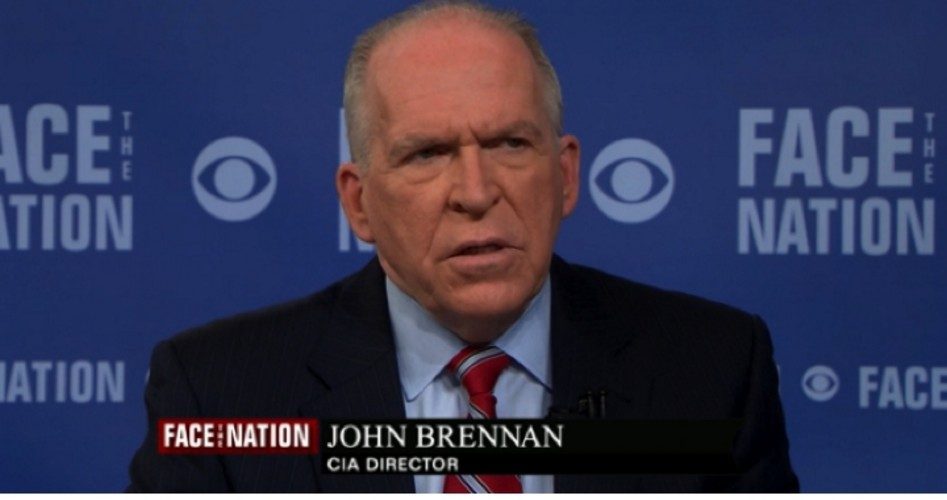

Appearing on the May 31 edition of the CBS show Face the Nation, Brennan was asked by host Bob Schieffer if President Barack Obama is “just trying to buy time” in the war on terrorism or if he’s “ready to make a full commitment” to winning it.

Brennan, naturally, replied that Obama was doing everything possible “to try to keep this country safe.” “There are,” he said, “no easy solutions” to the problems in the Middle East.

“I think the president has tried to make sure that we’re able to push the envelope when we can to protect this country,” Brennan continued. “But we have to recognize that sometimes our engagement and direct involvement will stimulate and spur additional threats to our national security interests.” (Emphasis added.)

Translated from its native Washingtonese, that means that when the U.S. government intervenes in foreign countries — by, for instance, sending in drones to wipe out people attending weddings or funerals or even schools — the families, friends, compatriots, and coreligionists of those who were killed just might decide to retaliate against Americans. In short, violence against foreigners begets violence against Americans.

While this may seem like common sense, such sentiments have been in short supply in America’s political discourse over the past 14 years. Ever since President George W. Bush declared that the 9/11 attacks were motivated by a hatred of freedom, there has been “an agreed-upon, bipartisan understanding that under no circumstances will officials or politicians acknowledge, or even explore, the concept that foreign policy activities might play a role in compelling U.S. residents [or, for that matter, foreigners], who would not otherwise consider terrorism, to plot and attempt attacks,” observed Micah Zenko, a fellow at — of all places — the Council on Foreign Relations and one of the first people to draw attention to Brennan’s remarks.

Indeed, so ingrained is this mindset among the political class that when then-Texas Representative Ron Paul suggested in a 2007 Republican presidential debate that the terrorists had “attacked us because we’ve been over there … bombing Iraq for 10 years,” former New York mayor Rudy Giuliani responded in stunned amazement that anyone could suggest “that we invited the attack because we were attacking Iraq.”

Brennan himself participated in the very same charade. In a January 2010 press conference on the attempted downing of an airliner by “underwear bomber” Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab, the late Helen Thomas repeatedly asked Brennan, then Obama’s counterterrorism adviser, what Abdulmutallab’s and other terrorists’’ “motivation” was. Brennan responded with the usual bromides about how “Al Qaeda is an organization that is dedicated to murder and wanton slaughter of innocents” and “is just determined to carry out attacks against the homeland.” That is, terrorists are simply evil people who want to harm innocent Americans for no particular reason (other than, perhaps, our rapidly dwindling liberties).

Abdulmutallab, for his part, said at his sentencing that he was motivated to attack the United States “in retaliation for U.S. support of Israel and in retaliation of the killing of innocent and civilian Muslim populations in Palestine, especially in the blockade of Gaza, and in retaliation for the killing of innocent and civilian Muslim populations in Yemen, Iraq, Somalia, Afghanistan and beyond, most of them women, children, and noncombatants.”

Moreover, noted Jon Schwarz of The Intercept, “the government’s own sentencing memorandum for Abdulmutallab cites this statement, and points out that trying ‘to retaliate against government conduct’ is part of the legal definition of terrorism.”

Abdulmutallab is hardly the only terrorist or would-be terrorist to state that U.S. foreign policy is what drove him to attack Americans. Faisal Shahzad, who tried to explode a bomb in Times Square in 2010, told a federal court that his attempted atrocity was in response to the United States’ “terrorizing the Muslim nations and the Muslim people” with invasions and drone strikes. And, of course, Osama bin Laden repeatedly announced that he wanted his fellow Muslims to attack America because of its sundry Middle Eastern interventions, not least of which was stationing troops in Muslim holy lands in Saudi Arabia — a grievance that then-Deputy Defense Secretary Paul Wolfowitz admitted in 2003 had “been a huge recruiting device for al Qaeda.”

Even non-terrorists living in countries attacked by the United States can see the effects of U.S. policy.

“What radicals had previously failed to achieve in my village, one drone strike accomplished in an instant: there is now an intense anger and growing hatred of America,” Yemeni activist Farea Al-Muslimi told the Senate Judiciary Committee in 2013, just six days after a drone attack on his village. Al-Muslimi told the panel he had “seen Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula use U.S. strikes to promote its agenda and try to recruit more terrorists.”

Brennan has surely known this all along — the CIA, after all, coined the term “blowback” to refer to the unintended negative consequences of U.S. intervention — and so has much of the rest of official Washington. They have, however, been loath to proclaim it because doing so might call into question the whole imperial enterprise, which could be very bad for both politicians and the military-industrial complex.

Still, with any luck, the breach of protocol in which Brennan engaged will lead to a wider discussion of U.S. foreign policy and its disastrous results. Perhaps then Americans will begin to demand that their government abide by the Founders’ wise counsel to enjoy “peace, commerce, and honest friendship with all nations” (Thomas Jefferson) instead of going “abroad in search of monsters to destroy” (John Quincy Adams).