Cuban President Raúl Castro Wednesday demanded the return of Guantanamo Bay to Cuban sovereign control as a condition of normalized relations with the United States. The United States has held a lease on the property since 1903 and the continued presence of a U.S. naval base on the site has been a point of contention between the two countries since Raúl’s brother Fidel seized control of Cuba in a communist revolution in 1959. Raúl, who succeeded his brother as president in 2008, raised the issue in a speech at the Summit of the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States in Costa Rica.

“The reestablishment of diplomatic relations is the start of a process of normalizing bilateral relations,” Castro said. “But this will not be possible while the blockade still exists, while they don’t give back the territory illegally occupied by the Guantanamo naval base.”

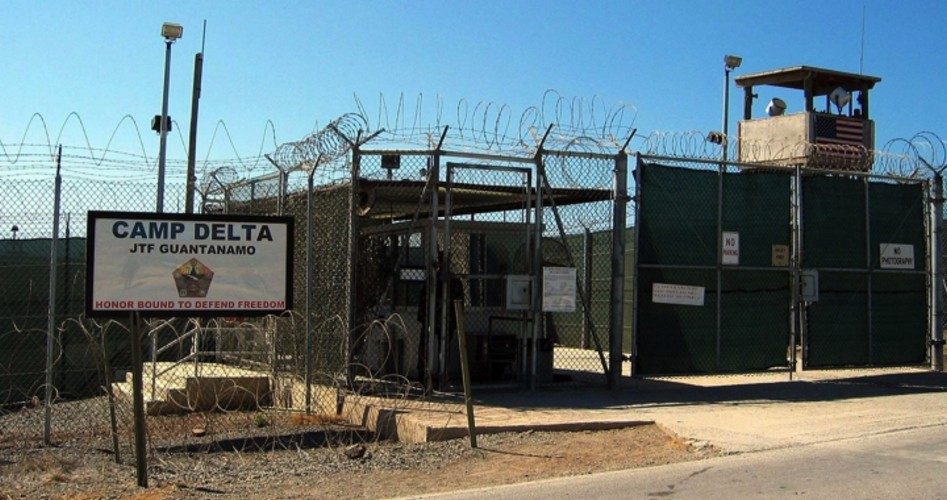

The United States began holding prisoners captured in Afghanistan and other international terrorism suspects at Guantanamo in January, 2002, four months after the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks on New York and Washington, D.C. President Obama has reduced the number of prisoners there and has repeatedly called for the closing of the detention center, a plan that has been consistently opposed by Congress. In December of last year, Presidents Obama and Castro announced plans for negotiations toward normalized relations between the two countries, including a lifting of the U.S. embargo on trade with Cuba and restoration of diplomatic relations that have been severed since 1961. High-level U.S. officials were in Havana last week for preliminary talks. Obama has not, however, mentioned any plan to return Guantanamo to Cuban control.

The United States has held a lease on the site as a coaling and naval station since 1903 when President Theodore Roosevelt signed a treaty with the new Cuban government, established after the liberation of the island from Spain in the Spanish-American war. The treaty called for the United States to pay Cuba $2,000 in gold coins per year. In 1934, the Franklin Roosevelt administration negotiated the new lease with Cuban officials, including Fulgencio Batista, who became the island’s iron-fisted ruler for the next 25 years. That agreement, still in effect, states: “Until the two Contracting Parties agree to the modification or abrogation of the stipulations of the agreement in regard to the lease to the United States of America of lands in Cuba for coaling and naval stations … the stipulations of that Agreement with regard to the naval station of Guantánamo shall continue in effect.”

Since both parties would have to agree to abrogation of the treaty, the United States has regarded its duration as open-ended, while the Cuban government has continued to protest the U.S. military presence on “occupied territory.” The United States, in fact, occupies the base rent-free, since the Castro government shows its non-recognition of the lease agreement by refusing to cash the checks for a little more than $4,000 that Washington sends each year. Fidel Castro wrote in an essay in 2007 that his government cashed one of the checks by mistake in the early days of the revolution. The checks are made out to the Treasurer General of the Republic, he wrote, an office that was abolished when Castro came to power.

U.S.-Cuban relations had begun deteriorating soon after Castro’s revolution overthrew the Batista regime and established a communist dictatorship on the island. Political prisoners were summarily executed by firing squads and Cuba consolidated ties with the Soviet Union. As Castro’s government nationalized foreign-owned properties on the island, the Eisenhower administration banned U.S. purchases of Cuban sugar and the sale of oil to what had become a de facto Soviet satellite. Seized American assets included vacation homes and bank accounts of American citizens, along with factories, mines, oil refineries, and properties belonging to Coca-Cola Co., Exxon, First National Bank of Boston, and other U.S. companies. It was, according to a 2009 article in the Inter-American Law Review, the “largest uncompensated taking of American property by a foreign government in history.”

In January 1961, President Eisenhower ordered the closing of the U.S. embassy in Havana and severed diplomatic relations with Cuba. The establishment of a trade embargo soon followed, while the naval base at Guantanamo continued to be a sore spot with the Cuban government. In February 1964, a minor crisis occurred when Castro, claiming local fishermen had been kidnapped by anti-Castro Cuban-Americans, temporarily cut off the water supply to the base. Unable to drive the United States out militarily, Castro decried the presence of the base in a 1985 speech in Nicaragua, saying, “What interest can we have in waging a war with our neighbors?” he said.

Yet Fidel’s regime supported guerilla warfare and insurrections in the effort to export Cuba’s communist revolution to other Latin American countries. Argentinian-born Marxist Ernesto “Che” Guevara, who became Fidel’s military adviser and minister of industry, led a war of insurrection in Bolivia where he was captured and killed by the Bolivian army in 1967. “Che” has remained a hero to leftists in the United States and other parts of the world long after his death.

By demanding a U.S. withdrawal from Guantanamo, Raúl Castro has raised another barrier to normalized relations between the United States and Cuba, a subject which has already drawn heavy opposition on Capitol Hill. Opponents of the move cite continued violations of human rights on the island as reason to continue the trade embargo and the withholding of diplomatic relations. Cuba also is one of four nations — along with North Korea, Syria, and Sudan — on the U.S. State Department’s list of State Sponsors of Terrorism. Removal of Cuba from that list is another of Castro’s demands for improved relations.