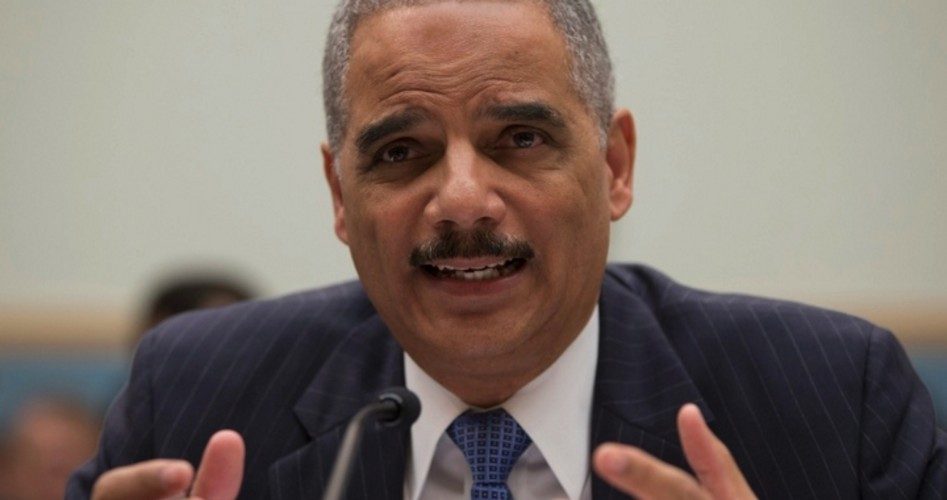

Attorney General Eric Holder (shown) issued the first official acknowledgement Wednesday that the United States has killed four U.S. citizens with drone strikes, including the targeted killing of Muslim cleric Anwar al-Awlaki in Yemen in September 2011. Holder also acknowledged the killing by drone strikes of three other Americans: Samir Khan, who was killed in the same strike that killed Awlaki; Awlaki’s 16-year-old son, Abdulrahman al-Awlaki, also killed in Yemen; and Jude Mohammed, killed in Pakistan.

“These individuals were not specifically targeted by the United States,” Holder said in a letter to congressional leaders that the New York Times obtained and disclosed in a report published Wednesday. That suggests the three, including Awlaki’s son, were killed in strikes on other targets, what is routinely described in military jargon as “collateral damage.” But Holder was quite explicit in acknowledging and defending the targeted killing of Awlaki, whose death President Obama announced on September 30, 2011. While crediting U.S. intelligence for tracking Awlaki, the president did not then or at any time since acknowledge that he was killed by a U.S. strike.

Holder said Awlaki had not only written messages urging attacks on Americans, but was also directly involved in planning attacks. The radical Muslim cleric was believed to be behind the attempted attack on a Detroit-bound airliner by the “underwear bomber” on Christmas Day, 2009. Holder said he also played a key role in a plot to bomb cargo planes headed for the United States in October 2010, having participated in the development and testing of the bombs.

“Moreover information that remains classified to protect sensitive sources and methods evidences Awlaki’s involvement in the planning of numerous other plots against US and Western interests and makes clear he was continuing to plot attacks when he was killed,” Holder told the congressional leaders.”The decision to target Anwar al-Awlaki was lawful, it was considered, and it was just,” the attorney general wrote.

The letter was delivered the day before President Obama is scheduled to discuss the war on terror and the policy governing drone strikes in an address at the National Defense University at Fort McNair in Washington. According to an unnamed White House official quoted by the Times, the president “will discuss why the use of drone strikes is necessary, legal and just, while addressing the various issues raised by our use of targeted action.”

Drone attacks have been a source of controversy in the United States, but even more so in countries like Pakistan, where they have been blamed for the deaths of innocent non-combatants. The number of civilians killed is undetermined and methods for counting them are open to dispute. Obama administration officials have said all military-age males killed in a strike zone are counted as combatants unless there is intelligence proving them innocent, the New York Times reported in a May 29, 2012 story.

According to the Times, Obama has signed a new classified policy guidance that will limit the instances in which the unmanned bombers may be used in strikes outside of overt war zones in countries like Pakistan, Yemen, and Somalia. Rules for strikes on foreign enemies will now be the same as those governing strikes on U.S. citizens believed to be terrorists. Lethal force will be used only against targets who pose “a continuing, imminent threat to Americans” and cannot feasibly be captured, Holder said in his letter.

The President’s former counterterrorism advisor and current CIA Director John Brennan was the first administration official to publicly acknowledge drone attacks, describing them as “consistent with the inherent right of self-defense.” Senator Rand Paul (R-Ky.) led a filibuster against Brennan’s confirmation as CIA chief earlier this year until Holder acknowledged the president has no legal right to target drone strikes on American citizens in the United States who are not actively involved in an attack against the nation. Holder’s answer did not, however, rule out targeting U.S. citizens overseas under conditions the attorney general laid out in a March 5, 2012 address Northwestern University Law School.

A U.S. citizen in a foreign land who is a “senior operational leader of al-Qaeda or associated forces” may be targeted for killing, Holder said, under the following conditions:

First, the U.S. government has determined, after a thorough and careful review, that the individual poses an imminent threat of violent attack against the United States; second, capture is not feasible; and third, the operation would be conducted in a manner consistent with applicable law of war principles.

Left unanswered is how it is determined that the targeted citizen does, in fact, pose “an imminent threat of violent attack against the United States.” Under U.S. law, a suspect may be prosecuted for making a violent attack or issuing a threat, but not for “posing” a threat, whatever that might mean. The Fifth and 14th amendments to the U.S. Constitution state that “no person,” citizen or not, may be “deprived of life, liberty, or property without due process of law.” But Holder insists that in matters of national security, the executive branch alone may determine whether a suspected American terrorist overseas may be deprived of life by his own government.

“Some have argued that the President is required to get permission from a federal court before taking action against a United States citizen who is a senior operational leader of al Qaeda or associated forces,” the attorney general noted in his Northwestern address. “This is simply not accurate. ‘Due process’ and ‘judicial process’ are not one and the same, particularly when it comes to national security. The Constitution guarantees due process, not judicial process.”

An administrative review, then, is all that is required to determine if a suspected terrorist may be hunted down and killed away from any battlefield. The president’s determination, according to Holder, satisfies the constitutional requirement of “due process.” A Justice Department memo, dubbed a “White Paper” on drone attacks, states that in assessing the evidence of “imminent” threat of an attack on the United States, the evidence need not be “clear,” the attack need not be “specific,” and “imminent” doesn’t necessarily mean anytime soon.

First, the condition that an operational leader pose an ‘imminent’ threat of violent attack against the United States does not require the United States to have clear evidence that a specific attack on U.S. persons and interests will take place in the immediate future.

The memo states what Holder has said in his public remarks, namely that while the Authorization for the Use of Military Force, passed by Congress shortly after the 9-11 attacks, may be cited as authorization for the drone strikes, the president, independent of that authority, has inherent powers as commander in chief of the armed forces to order such attacks to protect American lives and interests. The stark reality from that line of legal reasoning was summed up by Benjamin Friedman of the Cato Institute: “So a president, consulting with officials he can fire, is using a secret process that he can change to kill whomever he wants, wherever he wants, whether or not there is a war on, by saying the words al Qaeda.”

The Justice Department insists the president’s drone policy is open neither to judicial review, nor congressional debate. The “White Paper,” obtained by NBC News in February, was provided to members of the Senate Intelligence and Judiciary committee last June as a confidential document, not to be discussed publicly.

In granting Congress the power to declare war, the Constitution has assigned to lawmakers the power to decide whether, when, and with whom the United States shall be at war. Congress dodged that responsibility by delegating to the president an open-ended authority to wage war wherever he will. That the Obama administration has taken that to mean the right to target Americans for killing, regardless of whether they are armed and engaged in combat, says as much about the Congress as it does about the president.

As Friedman put it, “Obama has gone too far in exercising war powers because Congress let him.”

Photo of U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder: AP Images