U.S. Senator Ted Cruz (R-Texas) and U.S. Representative Francis Rooney (R-Fla.) last week introduced companion bills to add an amendment to the U.S. Constitution to limit U.S. senators to two six-year terms and U.S. representatives to three two-year terms. U.S. Senators Marco Rubio (R-Fla.), Mike Lee (R-Utah), David Perdue (R-Ga.), and Thom Tillis (R-N.C.) joined Cruz in co-sponsoring this amendment.

“For too long, members of Congress have abused their power and ignored the will of the American people,” Cruz said. “Term limits on members of Congress offer a solution to the brokenness we see in Washington, D.C. It is long past time for Congress to hold itself accountable. I urge my colleagues to submit this constitutional amendment to the states for speedy ratification.”

It is certainly true that “members of Congress have abused their power.” But how would term limits end this abuse? Would freshmen elected to fill the seats of term-limited congressmen necessarily be less abusive of power (i.e., more constitutionalist) than the congressmen they replace? And if it is true that freshmen congressmen can be expected to be more constitutionalist than their veteran colleagues, then why isn’t the current crop of freshmen (mostly far-left Democrats) elected last November more constitutionalist-minded than they actually are?

It is also true that congressmen have “ignored the will of the American people.” But when congressmen cannot run for re-election because of term limits, doesn’t that mean that these congressmen no longer have to worry about the will of their constituents? It is generally recognized that lame-duck legislative sessions held after an election are less responsive to the voters than regular legislative sessions held prior to the election. Yet limiting members of the House to three two-year terms would effectively make one third of the House lame-duck congressmen during regular legislative sessions.

And of course, term-limiting out of office a popular congressman that voters would want to re-elect would be an infringement upon the voters’ will.

Term limits are supported by many Americans who are fed up with Congress, yet apparently fail to realize that the only way to improve Congress is to improve the understanding of the voters who are responsible for who serves in Congress. In a press release, Representative Rooney claimed, “The American people support term limits by an overwhelming margin. I believe that as lawmakers, we should follow the example of our founding fathers, Presidents George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, who refused to consider public service as a career. Our history is replete with examples of leaders who served their country for a time and returned to private life, or who went on to serve in a different way.”

I doubt Representative Rooney realizes that viewing “public service” as a career has nothing to do with term limits. If a congressman or a senator wanted to demonstrate his appreciation of serving in the U.S. Congress as an act of patriotism and not patronage, he could simply refuse to seek re-election.

It’s as simple as this: just as there is no liberty without virtue, there is no virtue without liberty. After all, if a person is forced to do something — even something arguably good — the goodness of that act cannot logically be attributed to the person who committed the act. Praise for such acts are only merited when one does good, choosing it over evil.

Term limits seek to force federal representatives and senators to end their terms — whether they recognize limited power as a virtue or not — and it forces Americans not to vote for the same person over and over and over again, whether they care about “career politicians” or not.

Put another way: Cruz and Rooney have proposed a bill prohibiting Americans from voting for the candidate of their choice, placing their will above that of the people.

It seems odd that Cruz, a self-described conservative, would adopt such a progressive and paternalistic attitude toward the right of the people to elect their representatives, one of the most fundamental rights in a Republic.

And although Rooney’s statement claims that the idea of term limits is consistent with the intent of men like James Madison and Thomas Jefferson and with their concept of republicanism, that’s not true.

In a letter to a friend written in 1788, Thomas Jefferson identifies what he believed was the proper way to limit the time a man spent in government office.

“I apprehend that the total abandonment of the principle of rotation in the offices of president and senator will end in abuse. But my confidence is that there will for a long time be virtue and good sense enough in our countrymen to correct abuses.”

If we don’t have sufficient “virtue and good sense” to keep men from abusing power, do we really have any hope of maintaining republican liberty at all?

Alexander Hamilton in The Federalist, No. 72, expressed his sense of the question of term limits: “Nothing appears more plausible at first sight, nor more ill-founded upon close inspection.”

During the debates on the subject at the original constitutional convention in Philadelphia in 1787, Connecticut delegate Roger Sherman expressed a similar opinion:

“Frequent elections are necessary to preserve the good behavior of rulers. They also tend to give permanency to the Government, by preserving that good behavior, because it ensures their re-election.”

In The Federalist, No. 53, James Madison wrote:

No man can be a competent legislator who does not add to an upright intention and a sound judgement a certain degree of knowledge of the subjects on which he is to legislate. A part of this knowledge may be acquired by means of information which lie within the compass of men in private as well as public stations. Another part can only be attained, or at least thoroughly attained, by actual experience in the station which requires the use of it…. A few of the members [of Congress], as happens in all such assemblies, will possess superior talents; will, by frequent re-elections, become members of long standing; will be thoroughly masters of the public business, and perhaps not unwilling to avail themselves of those advantages. The greater the proportion of new members and the less the information of the bulk of the members, the more apt will they be to fall into the snares that may be laid for them.

At the Constitutional Convention of 1787, Gouvernor Morris spoke on the subject, too. Madison records Morris saying:

“The ineligibility proposed by the [term limits] clause as it stood tended to destroy the great motive to good behavior, the hope of being rewarded by a re-appointment. It was saying to him, “make hay while the sun shines.”

And, finally, John Adams wrote in his Defense of the Constitutions of the United States of America:

There is no right clearer, and few of more importance, than that the people should be at liberty to choose the ablest and best men, and that men of the greatest merit should exercise the most important employments; yet, upon the present [term limits] supposition, the people voluntarily resign this right, and shackle their own choice…. They must all return to private life, and be succeeded by another set, who have less wisdom, wealth, virtue, and less of the confidence and affection of the people.

There is wisdom in the Founders’ wariness of the concept of limiting corruption by limiting terms of representatives.

When viewed through the Founders’ lens, it becomes clear that an elected representative would likely be less attached to the attitudes of his constituents if he knew that no matter how he performed in Congress, his time among the lobbyists would eventually expire. In that case, a corrupt and designing politician would take maximum advantage of his access to graft in the limited time available to him.

The Founders learned this nuanced lesson during the time they lived under the Articles of Confederation. Article V of that first constitution mandated term limits for congressmen, mandating, “no person shall be capable of being a delegate for more than three years in any term of six years.”

When they were called to “to devise such further provisions as shall appear to them necessary to render the constitution of the Federal Government adequate to the exigencies of the Union” (language, curiously, nearly identical to that used by the contemporary con-con crowd, though they deny they are calling for a constitutional convention), the Founders replaced term limits with a plan they believed more consistent with timeless principles of republican government: frequent elections.

While it may be difficult to effect meaningful change with frequent elections, it is almost impossible to do so with term limits. Representatives and senators sitting in office for decades is not the problem. The problem is the surrender by states — forcibly and willingly — of sovereignty to the federal government.

With states becoming reliant on the federal government for over one-third and as much as almost one half of their budgets, it’s easy to see that having power over the federal purse multiplies the relative constitutional power of congressional office. The problem, then, isn’t the length of time in office, but the amount of power associated with those offices.

The solution, then, is restoring power to the states, rather than restricting artificially the right of the people to elect their representatives.

Why do these same people want to first, deny states the power to nullify unconstitutional acts of the federal government; and, second, destroy the liberty of the people to elect the candidates of their choice?

Again, turning to the Founders, Samuel Adams summed it up perfectly in 1790:

Much safer is it, and much more does it tend to promote the welfare and happiness of society to fill up the offices of Government after the mode prescribed in the American Constitution, by frequent elections of the people. They may indeed be deceived in their choice; they sometimes are; but the evil is not incurable; the remedy is always near; they will feel their mistakes, and correct them.

Rather than relying on nanny state “term limits” to restrain our liberty, let’s use frequent elections to restrain any legislator who abuses his access to power. And let us take the shackles off states and encourage them to exercise their power to refuse to enforce any act of the federal government that exceeds the power given to it in the Constitution.

As of the time of the writing of this article, Senator Cruz’s term limit amendment bill was co-sponsored only by Senators Rubio and Lee. The companion bill offered by Representative Rooney has 15 co-sponsors, including the usually constitutionally consistent Representative Thomas Massie (R-Ky.).

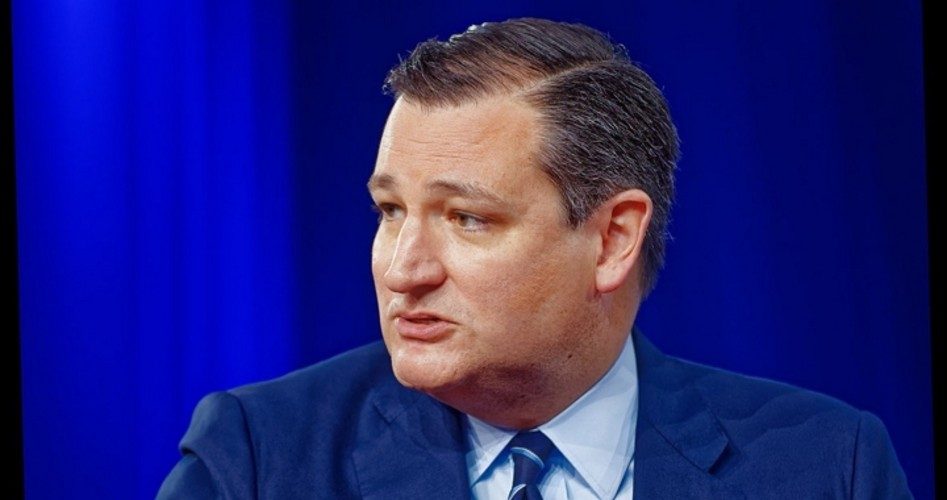

Photo of Sen. Ted Cruz: Michael Vadon