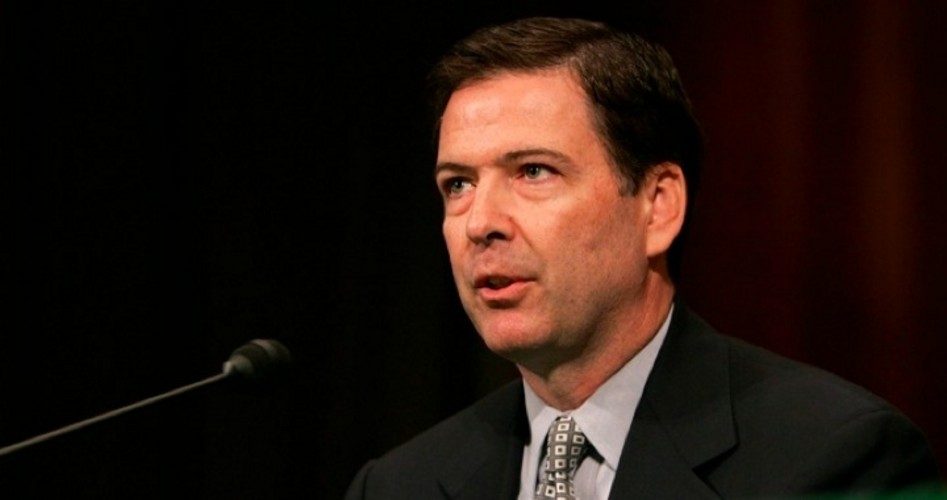

James B. Comey (shown), the man reported to be President Obama’s choice to succeed Robert Mueller as director of the FBI, vigorously supported the decision to imprison José Padilla indefinitely as an “enemy combatant.” Padilla, a U.S. citizen, was arrested at O’Hare International Airport in May 2002 for what then-Attorney General John Ashcroft said was his participation in a plot to detonate a radioactive “dirty bomb” in a major city somewhere in the United States. He was held without charge and without trial in a solitary confinement at a U.S. Navy brig in Charleston, South Carolina, for three and one-half years before being tried in a civilian court in Miami on charges unrelated to the alleged “dirty bomb.”

Padilla and two co-defendants were found guilty by a federal jury of conspiracy to murder, kidnap, and maim overseas, and of conspiring to provide and of providing material support for terrorists. Padilla is currently serving a sentence of 17 years and four months in a federal prison in Florence, Colorado. His lawyers claimed he was unable to participate in his own defense at trial after years of solitary confinement in a nine-foot-by-seven-foot cell, where, they said, he was frequently chained in painful “stress positions” and injected with mind-altering drugs.

Comey, a Republican, was a U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York at the time of Padilla’s arrest. He “aggressively defended” the designation of Padilla as an enemy combatant, according to the New York Times.

Comey also prosecuted attorney Lynne Stewart on charges arising from her representation of Omar Abdel-Rahman, who was convicted of seditious conspiracy and is now serving a life sentence. Stewart ran afoul of the special administrative measures governing public statements about a terror suspect, as well as communications between the suspect and his attorney. Stewart read at a press conference a statement of Rahman’s that authorities interpreted as an encouragement to violent insurrection in Egypt. She was convicted in 2003 of obstruction of justice and conspiracy to provide, and providing, material support to terrorism. She was sentenced to 10 years in prison.

Aside from the free speech issues involved in prosecuting an attorney for a public statement made on behalf of her client, some of the evidence used against Stewart was obtained through the use of wiretaps and secret cameras to record her conversations with Rahman. The electronic eavesdropping, authorized under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, makes a mockery of the longstanding legal principle of privileged conversations between attorney and client.

Comey nailed another Stewart, publisher and TV celebrity Martha Stewart, on charges stemming from an investigation into her sale of ImClone stock shortly before the Food and Drug administration announced its decision not to approve ImClone’s anti-cancer drug, Erbitux. If her sale were, as alleged, evidence of “insider trading,” the insiders were a remarkably large group. ImClone’s stock had been steadily falling for at least two weeks before Stewart unloaded her stock, as thousands of others had already done and were doing. No fewer than 7.7 million shares of ImClone stock were sold the same day Stewart sold her 3,298. That was on December 27, 2001, amid widespread and growing anticipation of an imminent negative FDA decision on ImClone’s application.

“After all,” wrote economist and syndicated columnist Alan Reynolds, “the FDA had only until the end of the year to decide one way or the other. It didn’t take a financial genius to figure out that every passing day of delay looked more ominous.”

Stewart was eventually convicted of making misleading statements to federal investigators and obstruction of justice, and was sentenced to a five-month jail term, followed by two years of supervised release. The quality of the justice she was convicted of obstructing is itself suspect. The House Energy and Commerce Committee had been investigating Stewart when it sent a letter to Attorney General Ashcroft on September 10, 2002, urging her prosecution because she “repeatedly has refused to be interviewed by committee staff — and her attorneys have stated that she will invoke her Fifth Amendment right.” Invoking one’s constitutionally guaranteed right is apparently grounds for prosecution in the minds of members of Congress and an ambitious U.S. attorney.

On the plus side, Comey, while serving as deputy attorney general under Ashcroft in 2004, is said to have argued strenuously against renewal of a secret, warrantless eavesdropping operation called the “President’s Surveillance Program.” Several Justice Department officials, including Comey and Mueller, reportedly threatened to resign if the program were continued. They stayed on when it was modified to meet their objections.

On the whole, Comey’s record does not inspire confidence that he would be a respecter of the Constitution and rights of the accused if, as expected, he is nominated and confirmed as the next director of the FBI.

When he was named deputy attorney general in late 2003, Christopher Dunn, associate legal director of the New York Civil Liberties Union, said, “Nothing about Mr. Comey’s tenure in New York suggests he will be a friend of the Constitution when he joins John Ashcroft in Washington.” Dunn sounded a bit more optimistic on May 31, telling the New York Times that Comey’s confirmation hearing “will provide an important opportunity to assure that the F.B.I. fully understands its role in protecting civil liberties.”

Photo of James Comey: AP Images