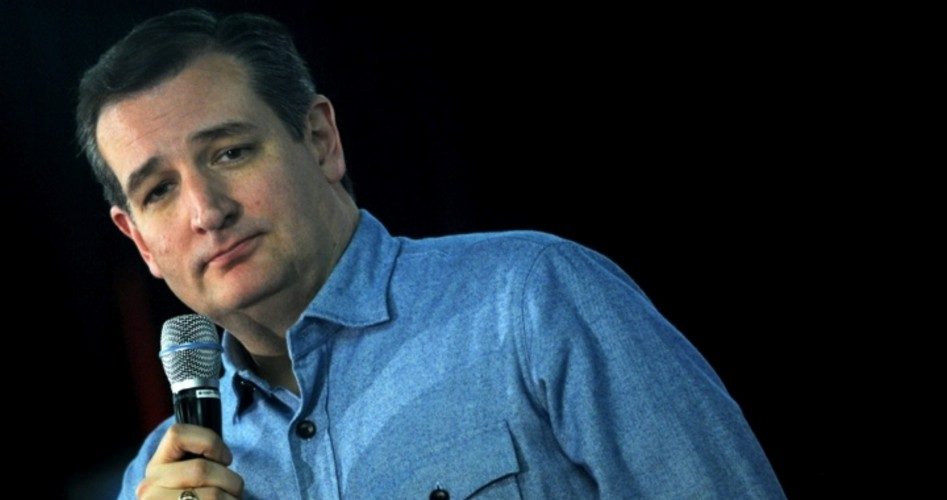

As Donald Trump’s presidential campaign continues to crescendo, his questions regarding the constitutional qualification of Senator Ted Cruz (shown) to be president are being taken seriously by scholars and the answers aren’t as clear as Cruz claims.

On January 25, Yahoo News reported that the latest “Congressional Research Service report is adding some new background on the controversy over U.S. presidential candidates like Ted Cruz who were born overseas and who are seeking office.”

Cruz was born in Alberta, Canada to a Cuban father and an American mother.

Yahoo’s recap of the CRS report states that, “While not mentioning Cruz directly, the analysis prepared for Congress recaps legal ‘birther cases’ since 2011, and at least in one paragraph, legislative attorney Jack Maskell states that it is unclear that a situation like Cruz’s has been settled definitively.”

At the center of the so-called birther question is Article II’s declaration that “No person except a natural born citizen, or a citizen of the United States, at the time of the adoption of this Constitution, shall be eligible to the Office of President.”

The CRS analysis (dated January 11, 2016) puts a finer point on the issue:

“Under the Constitution, only ‘natural born’ citizens are eligible to become President or Vice President of the United States. The Constitution nowhere defines this term, and its precise meaning is still uncertain. It is clear enough that native-born citizens are eligible and that naturalized citizens are not. The doubts relate to those who acquire U.S. citizenship by descent, at birth abroad to U.S. citizens….

The uncertainty concerning the meaning of the natural-born qualification in the Constitution has provoked discussion from time to time, particularly when the possible presidential candidacy of citizens born abroad was under consideration. There has never been any authoritative adjudication. It is possible that none may ever develop. However, there is substantial basis for concluding that the constitutional reference to a natural-born citizen includes every person who was born a citizen, including native-born citizens and citizens by descent. [Emphasis in original.]

Although the Cruz campaign has “shrugged off any political implication” of his questionable constitutional qualifications, Americans devoted to upholding constitutional standards and the rule of law are likely a bit less nonchalant.

In order to remain true to the Founders’ intent in drafting Article II, one must delve into the historical origins of the “natural born citizen” phrase as used in the Constitution. As the CRS report indicates, the Constitution does not define natural-born citizenship, and the Supreme Court and Congress have likewise shied away from putting a finer point on this crucial characteristic.

The term “natural-born citizen” comes from the English concept of “natural-born subject,” which came from Calvin’s Case, a 1608 decision.

Natural-born subjects were those who owed allegiance to the king at birth under the “law of nature.” The court concluded that under natural law, certain people owed duties to the king, and were entitled to his protection, even in the absence of a law passed by Parliament.

Our own Founding Fathers, nearly every one of whom was born in some outpost of the British Empire, feared the damage that could come from such divided loyalty. They instituted the “natural born citizen” qualification in order to avoid what Gouverneur Morris described during the Constitutional Convention as “the danger of admitting strangers into our public councils.”

As famed jurist of the early republic St. George Tucker, a contemporary of Morris, explained:

That provision in the constitution which requires that the president shall be a native-born citizen (unless he were a citizen of the United States when the constitution was adopted) is a happy means of security against foreign influence, which, wherever it is capable of being exerted, is to be dreaded more than the plague. The admission of foreigners into our councils, consequently, cannot be too much guarded against; their total exclusion from a station to which foreign nations have been accustomed to attach ideas of sovereign power, sacredness of character, and hereditary right, is a measure of the most consummate policy and wisdom.

The Founders did not come to this understanding on their own. The eminent men who influenced their understanding of such concepts defined them in very clear and convincing terms, and none did so more persuasively than Emer de Vattel. The Swiss-born Vattel was immeasurably influential on the leading men of the Founding Generation.

For example, in 1775, Benjamin Franklin commented on the immense importance of de Vattel’s The Law of Nations, then ordered three copies of the latest editions to be added to the Library Company of Philadelphia.

On December 9 of 1775, Franklin wrote to de Vattel’s editor, C.G.F. Dumas, “I am much obliged by the kind present you have made us of your edition of Vattel. It came to us in good season, when the circumstances of a rising state make it necessary frequently to consult the Law of Nations. Accordingly, that copy which I kept has been continually in the hands of the members of our congress, now sitting, who are much pleased with your notes and preface, and have entertained a high and just esteem for their author.”

Even George Washington kept a copy he borrowed in 1789 from New York Society Library.

In 1772, Samuel Adams cited the Swiss jurist, writing, “Vattel tells us plainly and without hesitation, that the supreme legislative cannot change the constitution.” Sam’s equally eminent cousin, John, quoted the same statement by Vattel during a 1773 debate with the colonial governor of Massachusetts.

Further proof of Vattel’s impression on the Founders is the fact that Vattel’s interpretations of the law of nature were cited more frequently than any other writer’s on international law in cases heard in the courts of the early United States, and The Law of Nations was the primary textbook on the subject in use in American universities.

With this sanction in mind, consider Vattel’s statement on the subject of natural-born citizens, as written in Book I, Chapter 19 of The Law of Nations:

The citizens are the members of the civil society; bound to this society by certain duties, and subject to its authority, they equally participate in its advantages. The natives, or natural-born citizens, are those born in the country, of parents who are citizens. As the society cannot exist and perpetuate itself otherwise than by the children of the citizens, those children naturally follow the condition of their fathers, and succeed to all their rights. The society is supposed to desire this, in consequence of what it owes to its own preservation; and it is presumed, as matter of course, that each citizen, on entering into society, reserves to his children the right of becoming members of it. The country of the fathers is therefore that of the children; and these become true citizens merely by their tacit consent. We shall soon see whether, on their coming to the years of discretion, they may renounce their right, and what they owe to the society in which they were born. I say, that, in order to be of the country, it is necessary that a person be born of a father who is a citizen; for, if he is born there of a foreigner, it will be only the place of his birth, and not his country.

Having learned this lesson from Vattel, the Founders were concerned with the possibility of foreign influence. The fear, however, was not that foreign parents might persuade a president to favor this or that country, but that there existed even the possibility of such an influence.

Consider, for example, Hamilton’s opinion set out in The Federalist, No. 68 wherein he writes that the electoral college would serve to ensure that any and every candidate for president would “be in an eminent degree endowed with the requisite qualifications.”

It would seem, then, that “an eminent degree” is a bar set much higher than “more likely than not” or “could be argued,” the statements used to support the constitutional qualification of Ted Cruz. There is no debate that at the time of his birth, Cruz’s father was not without allegiance to a foreign power, which was the sine qua non of natural-born citizenship status.

While the question of allegiance of Cruz’s father may be debatable (Cuba or Canada), one could argue that once we even entertain such suspicions, we fall very short of the “eminent degree” standard established by Hamilton in The Federalist.

Finally, the reader is directed to the citizenship statute of Virginia penned in 1779 by Thomas Jefferson. In this law, Jefferson clearly indicates that the infant’s father, if living, must be a citizen. The allegiance of the child’s mother only becomes a factor in the equation if the father is no longer living. Here is the relevant language from that law:

… All infants wheresoever born, whose father, if living, or otherwise, whose mother was, a citizen at the time of their birth, or who migrate hither, their father, if living, or otherwise their mother becoming a citizen, or who migrate hither without father or mother, shall be deemed citizens of this commonwealth, until they relinquish that character in manner as herein after expressed: And all others not being citizens of any the United States of America, shall be deemed aliens.”

So, while many conservatives and constitutionalists have rightly praised Ted Cruz’s support of several constitutionally sound causes, his birthplace allows him to serve in the Senate, but it may not leave him constitutionally qualified to serve as president.

Photo: AP Images