Indiana state Senator David Long — a Republican — is once again demonstrating his lamentable lack of understanding of the facts of federalism and his own constitutionally mandated oath to protect the Constitution.

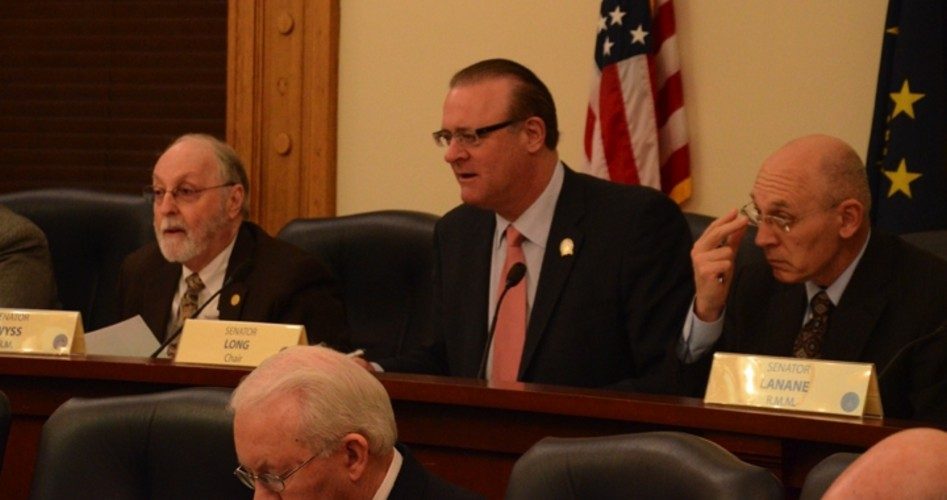

Long (shown in center) has invited state legislators to attend a second “Mt. Vernon Assembly” scheduled for June 12-13.

According to information released by Long and Mt. Vernon organizers, three lawmakers from each state will be invited to convene at the Indiana state House to set rules for a third meeting to be held in December. The December assembly plans to formally set in motion an Article V constitutional convention.

There is much wrong with Long and his agenda, but perhaps the worst is his habit of misrepresenting the Constitution, the method of its original ratification, and the type of government it established.

“States are the laboratories of democracy,” Long said. “If something gets done properly, it doesn’t come from Washington. It comes from the states.”

“What we will be doing in Indianapolis in the second week of June is try to put the structure and rules of a convention,” Long said, as reported by local media. “If we do have that, there will be an agreed upon process that the states, possibly through resolution, will be adopting. Here’s how you officially adopt your delegates. Here’s how we run it. In this way, no one could argue that you’ve had a runaway convention.”

First, allow me to correct the senator’s statement about states being “laboratories of democracy.”

Robert Welch, the founder of The John Birch Society, explained the key distinction between “democracy” and “republic”:

When our Founding Fathers established a republic, in the hope, as Benjamin Franklin said, that we could keep it, and when they guaranteed to every state within that republic a republican form of government, they well knew the significance of the terms they were using. And they were doing all in their power to make the features of government signified by those terms as permanent as possible.

They also knew very well indeed the meaning of the word democracy, and the history of democracies; and they were deliberately doing everything in their power to avoid for their own times, and to prevent for the future, the evils of a democracy.

Historical examples of this understanding abound, but suffice these examples from Welch’s speech to suffice:

On May 31, 1787, Edmund Randolph told his fellow members of the newly assembled Constitutional Convention that the object for which the delegates had met was “to provide a cure for the evils under which the United States labored; that in tracing these evils to their origin every man had found it in the turbulence and trials of democracy.”

The delegates to the convention were clearly in accord with this statement. At about the same time another delegate, Elbridge Gerry, said: “The evils we experience flow from the excess of democracy. The people do not want [that is, do not lack] virtue; but are the dupes of pretended patriots.” And on June 21, 1788, Alexander Hamilton made a speech in which he stated:

It had been observed that a pure democracy if it were practicable would be the most perfect government. Experience had proved that no position is more false than this. The ancient democracies in which the people themselves deliberated never possessed one good feature of government. Their very character was tyranny; their figure deformity.

At another time Hamilton said: “We are a Republican Government. Real liberty is never found in despotism or in the extremes of Democracy.” And Samuel Adams warned: “Remember, Democracy never lasts long. It soon wastes, exhausts and murders itself! There never was a democracy that ‘did not commit suicide.’”

James Madison, one of the members of the convention who was charged with drawing up our Constitution, wrote as follows:

Democracies have ever been spectacles of turbulence and contention; have ever been found incompatible with personal security, or the rights of property; and have in general been as short in their lives as they have been violent in their deaths.

I’m hopeful that that history lesson helps Senator Long and he will avoid referring to the governments in the states or the union as a democracy.

Next, Long’s belief that an Article V convention could be controlled and that pre-arranged rules could prevent a “runaway convention” deserves to be corrected.

Advocates of an Article V con-con argue that the convention they propose could not be hijacked by powerful interests with other agendas because the delegates would be bound by state instructions to limit their work to this or that pre-approved amendment (typically a balanced budget amendment). This view assumes that only delegates from states applying for such a limited convention would participate. It also ignores historical precedent showing that delegates can and do act independently.

The Convention of 1787 — the convention that gave us the Constitution — was called by Congress and limited by pre-arranged mandate “to devise such further provisions as shall appear to them necessary to render the constitution of the Federal Government [the Articles of Confederation] adequate to the exigencies of the Union.” But on the very first day of the Convention of 1787, delegates from Virginia exceeded this purpose by throwing out the Articles of Confederation (the constitution in force at the time) altogether and writing an entirely new Constitution.

Under the rules of the Convention of 1787, the new Constitution could be ratified by nine of the 13 states: “The Ratification of the Conventions of nine States, shall be sufficient for the Establishment of this Constitution between the States so ratifying the Same.” And that’s exactly what was done, despite the fact that the then-existing Articles of Confederation mandated that no “alteration” be made unless it’s “agreed to in a Congress of the United States, and be afterwards confirmed by the legislatures of every State.”

That’s quite a change, and this changing of the rules of ratification by the convention was undoubtedly done to improve the prospects of the new Constitution being ratified.

That new Constitution proved to be a great blessing for our country. But the Convention of 1787 was still a runaway convention in the sense that it far exceeded the purpose for which it was called. A second constitutional convention could also run away, though this time the result could be harmful or even disastrous.

In such an “unlikely” eventuality, convention advocates claim, the state legislatures would have the final say and they would never ratify the bait-and-switch amendments. But that claim cannot be said with certainty, considering that, as mentioned above, state legislatures have ratified harmful amendments in the past. Moreover, the state legislatures may not have the final say.

First of all, under Article V, Congress decides between two modes of ratification — ratification by three-fourths of the state legislatures, or by three-fourths of state ratifying conventions that may or may not reflect the will of the legislatures. There is a historical precedent for this: Congress submitted the 21st Amendment repealing Prohibition to state ratifying conventions. Second, the convention could conceivably change the ratification rules, as was done by the Convention of 1787.

When the first Mount Vernon Assembly adjourned last December, the 97 state legislators who attended report that the meeting was a success.

On her Facebook page, attendee and Arizona State Representative Kelly Townsend reported that the lawmakers gathered “to discuss a potential amendment to the US Constitution,” but that they did not discuss “what that amendment would be.”

Many fiscal conservatives believe that a constitutional convention needs to be called in order to bring about a balanced federal budget, despite the dangers of a runaway convention. But the fact of the matter is that determined citizens and state legislators could rescue the United States from its financial peril without resorting to opening up the Constitution to tinkering by delegates to a constitutional convention, many of whom would be bought and paid for by special interests and corporations.

Long is wrong on so many points, including this notion that he expressed in regard to a balanced budget amendment: “There are a number of different ideas out there. Spending and fiscal restraint seem to be the common discussion right now that almost everyone, Republicans and Democrats, can agree on.”

Will the delegates at his dream constitutional convention agree on the other amendments that will undoubtedly be brought to the floor by the con-con crowd’s progressive collaborators?

There is no reason we should ever allow this scenario to play out. The push for an Article V convention can be stopped and it begins by letting Long and his colleagues know that there are constitutionalists in this country who appreciate the dangers that lurk in an Article V convention.

Joe A. Wolverton, II, J.D. is a correspondent for The New American and travels nationwide speaking on nullification, the Second Amendment, the surveillance state, and other constitutional issues. Follow him on Twitter @TNAJoeWolverton and he can be reached at [email protected].