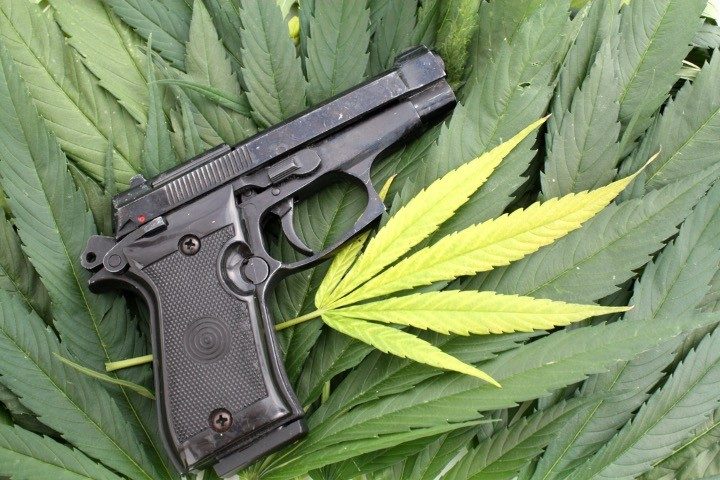

A three-judge panel of the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled unanimously on Wednesday that federal charges against a gun owner who also occasionally uses marijuana be dismissed. The panel went further, writing that the law itself is unconstitutional.

Overview

The panel, made up of two Trump appointees and one Biden appointee, agreed that charges against Paola Connelly, a Texas gun owner and occasional user of marijuana, must be dismissed:

Paola Connelly is a non-violent, marijuana smoking gunowner.

El Paso police came to her house in response to a “shots fired” call. When they arrived, they saw John, Paola’s husband, standing at their neighbor’s door firing a shotgun.

After arresting him, they spoke with Paola, who indicated that she would at times smoke marijuana as a sleep aid and for anxiety.

A sweep revealed that the Connellys’ home contained drug paraphernalia and several firearms, including firearms owned by Paola.

There was no indication that Paola was intoxicated at the time.

Under federal law 18 USC § 922(g)(3), it “shall be unlawful for any person … who is an unlawful user of or addicted to any controlled substance” to possess a firearm. Accordingly, Paola was charged with violating that federal law. The district judge found her innocent. The federal government appealed. The court noted:

This appeal asks us to consider whether Paola’s Second Amendment rights were infringed, and the answer depends on whether § 922(g)(3) is consistent with our history and tradition of firearms regulation.

The short of it is that our history and tradition may support some limits on a presently intoxicated person’s right to carry a weapon … but they do not support disarming a sober person based solely on past substance usage.

Nor, contrary to what the government contends, do restrictions on the mentally ill or more generalized traditions of disarming “dangerous” persons apply to nonviolent, occasional drug users when of sound mind.

U.S. attorneys did their best to find relevant laws providing the “historical” relevance or analogues for such a law now required under the Supreme Court’s ruling in Bruen (New York State Rifle & Pistol Association, Inc. v. Bruen), decided in 2022. They failed to do so. And so the court ruled that, “Marijuana user or not, Paola is a member of our political community and thus has a presumptive right to bear arms. By infringing on that right, [the federal law] contradicts the Second Amendment’s plain text.”

The Feds’ Arguments

The U.S. attorneys presented three arguments supporting the federal law’s constitutionality: 1) there were laws from the past disarming the mentally ill; 2) there were laws from the past that disarmed “dangerous” individuals, and 3) there were intoxication laws from the beginning of the Republic.

The three-judge panel dismissed each of them. They noted that “mental illness and drug use are not the same thing … [and] there are no clear sets of positive-law statutes concerning mental illness and firearms from the Founding.”

First, they ruled that “laws designed to disarm the severely mentally ill do not justify depriving those of sound mind their Second Amendment rights,” adding:

The analogy stands only if someone is so intoxicated as to be in a state comparable to “lunacy.” Just as there is no historical justification for disarming citizens of sound mind, there is no historical justification for disarming a sober citizen not presently under an impairing influence.

Secondly, U.S. government attorneys claimed that “history and tradition” make the federal law viable and enforceable in this case. But the panel tossed this argument as well. “Our history and tradition of disarming ‘dangerous’ persons does not include non-violent marijuana users like Paola,” they noted, adding:

Indeed, not one piece of historical evidence suggests that, at the time they ratified the Second Amendment, the Founders authorized Congress to disarm anyone it deemed dangerous….

The government identifies no class of persons at the Founding who were “dangerous” for reasons comparable to marijuana users….

The government provides no meaningful response to the fact that neither Congress nor the states disarmed alcoholics, the group most closely analogous to marijuana users in the 18th and 19th centuries.… The government offers no Founding-era law or practice of disarming ordinary citizens for drunkenness, even if their intoxication was routine.

But the real target of the ruling by the three-judge panel of the 5th Circuit was the law itself:

Boiled down, § 922(g)(3) is much broader than historical intoxication laws.

These laws may address a comparable problem — preventing intoxicated individuals from carrying weapons — but they do not impose a comparable burden on the right holder….

Section 922(g)(3) goes much further: it bans all possession, and it does so for an undefined set of “user[s],” even while they are not intoxicated.

The Ruling

The court concluded:

Paola stated that she would at times partake as a sleep aid or to help with anxiety, but we do not know how much she used at those times or when she last used, and there is no evidence that she was intoxicated at the time she was arrested.

Indeed, under the government’s reasoning, Congress could (if it wanted to) ban gun possession by anyone who has multiple alcoholic drinks a week from possessing guns based on the intoxicated carry laws.

The analogical reasoning Bruen … prescribed cannot stretch that far.

The history and tradition before us support, at most, a ban on carrying firearms while an individual is presently under the influence.

By regulating Paola based on habitual or occasional drug use, § 922(g)(3) imposes a far greater burden on her Second Amendment rights than our history and tradition of firearms regulation can support.

We AFFIRM the judgment of dismissal….

This is a remarkable ruling, even though it affects only the states over which the Fifth Circuit has jurisdiction — Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas. The government could appeal to the full (en banc) court for review. If the full court affirms the panel’s ruling, it would set a precedent for nationwide challenges to the unconstitutional law.