ITEM: In a column entitled "Benevolence amid an orgy," in the Boston Globe on October 6, Kevin Cullen wrote: "But there was one thing tacked on the bailout package that was not about someone's bottom line. There was, amid all this cynical politicking, an example of politics working for the better of people because of better people. Tacked onto the bailout was legislation requiring insurance firms to treat those who suffer from mental illness no differently from those with physical ailments. If the bailout of financial institutions was an example of special interests trumping politics, then the passage of the mental health parity act is a case of politics trumping special interests."

ITEM: The Des Moines Register commented on October 6: "There are good fats and there are bad fats. Among the lard attached to the massive Wall Street bailout legislation was some good fat: requiring insurance companies to treat physical and mental-health treatment the same. Mental-health parity doesn't belong in an economic rescue bill, but Congress is right to finally be addressing it."

The Register asserted: "Ensuring Americans get adequate mental-health coverage requires help from Congress because this country has a hodge-podge system of insurance regulation. Some health plans are regulated by states and some by the federal government. Even though Iowa lawmakers required mental-health parity a few years ago, the mandate doesn't apply to about 75 percent of Iowans not covered by state-regulated plans. A federal mandate, however, potentially reaches 113 million Americans. That would ensure equal treatment for patients and send a long-overdue message that mental illness is a real disease worthy of equal attention."

CORRECTION: With the financial world in free fall, triggered in part by irresponsible federal tinkering with the housing market, Congress decided it needed to do something about the high cost of healthcare: make it more expensive.

Having done its utmost to bankrupt the banking industry, Washington opted to help sicken the healthcare industry. While everyone was distracted with the larger implications of the federal bailout for Wall Street, legislators used the crisis to roll in to the $700 billion so-called rescue legislation a special-interest provision that had fallen short of passage for a dozen years despite the best lobbying efforts of those who would directly benefit from the new federal mandate, a requirement for "mental health parity."

This will increase the overall cost of healthcare and insurance and could even cause some insurers to drop their existing mental-health coverage because they can't afford "parity." When the dust clears, no doubt many of the same legislators will decry the high cost of healthcare, bemoan that not everybody has insurance coverage, and demand that more federal laws are needed to make all of this affordable.

It should go without saying, but finding fault with this devious move by Congress should not be seen as an attack on those who are mentally ill. One the other hand, proponents of new federal mandates love to equate how much they spend with their empathy and concern for the afflicted. It is a lot easier to be an altruist when the costs are borne by others.

Yes, this legislation has a waiver for companies of fewer than 50 employees. (One might cynically wonder: if this is such a great deal, why are they excluded? Just wait.) In order to get this mandate through Congress, its longtime promoters had to scale back some demands — for now. As the New York Times noted, sponsors of the bill in the House "agreed to drop a provision that required insurers to cover treatment for any condition listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, published by the American Psychiatric Association. Employers objected to such a requirement, saying it would have severely limited their discretion over what benefits to provide. Among the conditions in the manual, critics noted, are caffeine intoxication and sleep disorders resulting from jet lag."

Proponents of the new federal requirement also found a congressional study that estimated (based on a previous bill) that the legislation would "only" cost $3.4 billion over a decade. More honest advocates acknowledged that they had no idea what the eventual price tag might be. Cost estimates in Washington are usually low. Having gotten this version through, lobbyists for what should have been called the Health Premium Escalation and Psychiatrists' Full-Employment Act will likely be back at a future date to broaden the mandate.

The potential for abusing the system has just gotten greater. This is not just because mental illness is involved — when a cure is much less obvious than for many physical ailments — but because third-party insurance is involved. When a patient's medical bills are paid for by a third party (such as governments or insurance companies), there are numerous adverse effects. Human nature being what it is, patients overuse medical services because those resources seem to be free or inexpensive. Providers of services have a vested interest in more expensive or lengthier treatments because their market is guaranteed by the third-party payers. Again, it should go without saying that it is not an indictment of all of those in any profession to observe the shortcomings of some. Yet, in this case, the government's actions are likely to bring out the worst in those who find it profitable to game the system.

Consider the following conclusion drawn some time ago by the National Center for Policy Analysis:

A common observation in the mental health field is that the number of visits that it takes to "cure" a patient often miraculously equal the maximum number of visits allowed under the patient's insurance plan. Similarly, the number of days in a hospital or other institution needed to "cure" a patient often miraculously equal the maximum allowed by insurance. Providers tend to provide as long as insurance pays.

Thomas Szasz, a professor emeritus of psychiatry at the SUNY Upstate Medical University in Syracuse, has been an outspoken opponent of what might be called the mental-health establishment, which has made him a controversial figure. His piece in The Freeman in March 2002, "Parity for Mental Illness, Disparity for Mental Patients," all by itself probably ensured that he wouldn't be invited to the signing of the huge bailout bill to which this legislation was attached like a lamprey. Dr. Szasz wrote: "Advocating 'parity for mental illness' is a hoax. The supporters of 'mental health parity' do not want parity for mental patients: They do not seek equal 'legal treatment' by legislators and courts for mental patients and medical patients. What they want is parity for psychiatrists: They seek equal 'monetary treatment' by health insurance companies for psychiatrists and other physicians."

Keep in mind that mental-health parity legislation passed the Congress before, in 1996, but this wasn't enough for its advocates, lending credence to the assumption that they'll be back again.

In many cases, the state governments already require insurers to cover all sorts of mental-health treatments; now, the feds are also demanding that caps and coverages for these services be equalized with physical treatments. As a member of a benefit consulting firm happily told the New York Times: "A large majority of health plans currently have limits on hospital inpatient days and outpatient visits for mental health treatments, but not for other treatments. They will have to change their plan design."

Where, in the name of James Madison, is the authority for that found in the U.S. Constitution?

More insidiously, this legislation was passed because most attention was focused on the much larger financial bailout provisions. It took a shifty Senate move to fold disparate legislative pieces together. As noted, rather dispassionately, by Congressional Quarterly as the move was about to take place: "The Senate will offer the bailout and tax-extenders language as a substitute amendment to a House-passed mental health parity bill (HR 1424). Senators can amend the substitute. The House bill essentially will be a shell — a move that allows the Senate to work around the constitutional requirement that revenue-related legislation originate in the House."

No, this was not a daft move by lawmakers who are non compos mentis. It was a calculated, underhanded way to slip us our medicine as if we were their pets, infants, or wards in need of treatment — all with our money and for our good, of course.

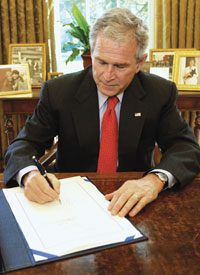

AP Images