The U.S. government, under the direction of Health and Human Services (HHS) Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., is assembling what may soon become one of the largest centralized health databases in American history. Spearheaded by newly appointed NIH Director Dr. Jay Bhattacharya, the project is framed as a bold attempt to identify the root causes of autism — a condition Kennedy rightfully called a “preventable disease.”

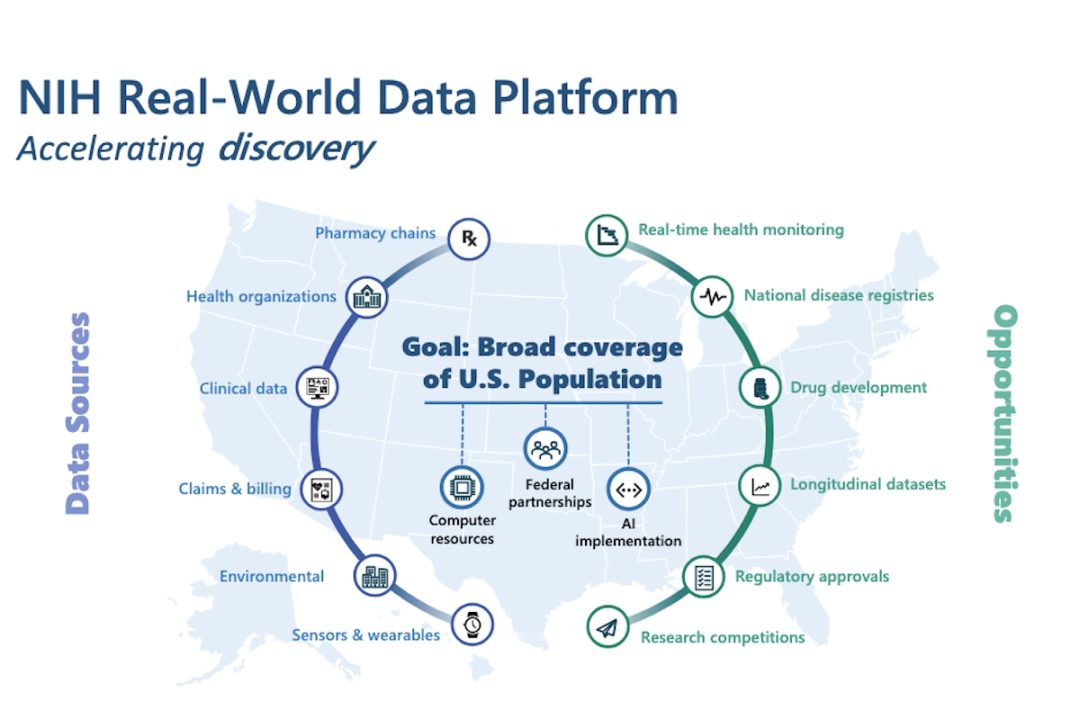

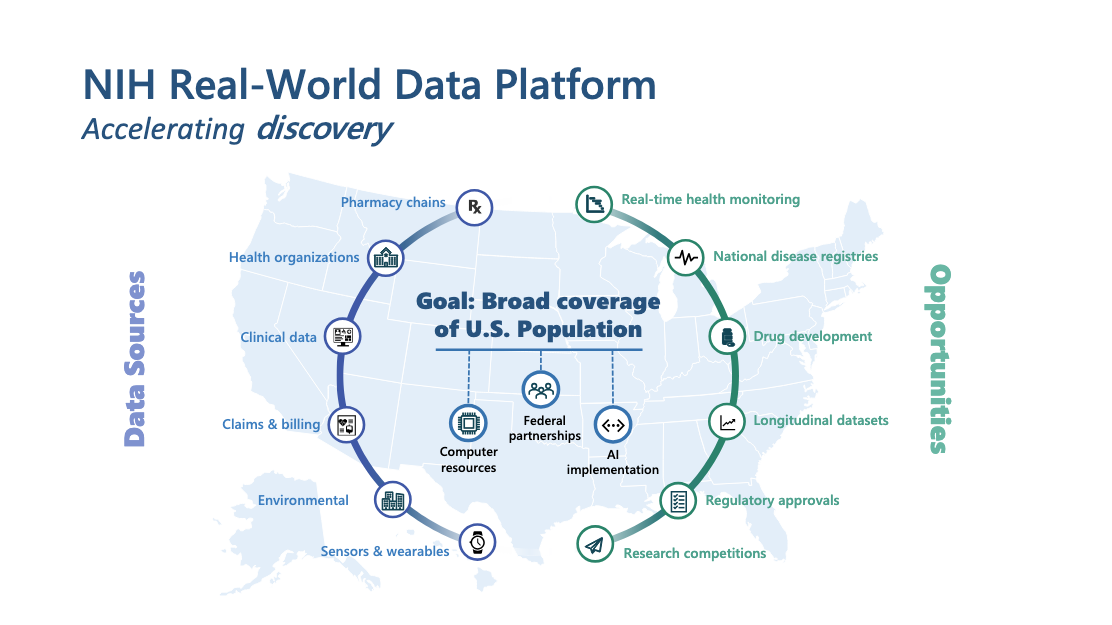

To do so, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) is compiling records from both public and private sources. This includes pharmacy transactions, lab test results, genomic data from Veteran Affairs (VA) and the Indian Health Service, Medicare and Medicaid claims, private insurance billing, and even data from wearables like smartwatches.

A new national registry for autism diagnoses will also be integrated. According to Bhattacharya, this aggregation effort is necessary to overcome the “fragmentation” in current health data infrastructure, as quoted by CBS News. He reportedly told NIH’s Council of Councils on Monday,

The idea of the platform is that the existing data resources are often fragmented and difficult to obtain. The NIH itself will often pay multiple times for the same data resource. Even data resources that are within the federal government are difficult to obtain.

What the Government Will Know

Once completed, the consolidated platform will grant researchers near-total vision into the medical histories, treatments, behaviors, and genetic profiles of millions of Americans.

Bhattacharya confirmed that 10 to 20 external research teams will be granted access. These researchers won’t be allowed to download the data, but will analyze it through secure portals. The government promises “state-of-the-art” protections — but the scale of what’s being collected, and the open question of who may tap into it later, raises deeper concerns.

The data sources span nearly every facet of personal health: prescription records, clinical and genomic files from hospitals, insurance claims, smart-device metrics and environmental exposure logs.

And this isn’t just about autism. Bhattacharya’s presentation made clear the goal is “broad coverage of the U.S. population.” To achieve that, the system will lean on federal partnerships, AI integration, and high-powered computing infrastructure.

The director said the platform will serve wider aims:

What we’re proposing is a transformative real-world data initiative… for chronic disease and autism research.

In other words, the initiative only begins with autism research. What follows is harder to control.

Other Use Cases

Indeed, autism study may be the starting point, but the platform is built for much more. Bhattacharya outlined uses beyond diagnostics — real-time health monitoring, national disease registries, longitudinal tracking, drug development, and streamlining regulatory approvals.

Once the infrastructure is in place, the lines between research, surveillance, and policy enforcement grow thinner. A dataset this comprehensive doesn’t just inform — it enables. What begins as scientific inquiry can evolve into a tool for control, standardization, or exclusion, depending on who holds the keys.

Its utility is undeniable. So is its potential reach.

A Registry, and the Ghosts It Awakens

Among the more quietly introduced components of the initiative is a national registry of Americans diagnosed with autism. The new registry, first reported by CBS, was mentioned only briefly by Bhattacharya, according to a transcript of his remarks.

Notably, a national autism tracking system already exists. The CDC’s Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring (ADDM) Network has monitored autism prevalence for over two decades. But its model is based on anonymized, regional record reviews and does not create a centralized list of individuals. In the context of Bhattacharya’s vision, the new registry will likely be fundamentally different — positioned within a broader platform designed to integrate medical, behavioral, and genomic data at the federal level.

It didn’t take long for social media to respond. Critics across platforms condemned the move as a step toward eugenics — a term that resurfaced with disturbing frequency. While no government official has explicitly endorsed such intent, the historical context is hard to ignore. Registries built around perceived genetic “abnormality” were central to some of the darkest policies of the 20th century.

This isn’t fringe paranoia. Creating a federal list based on neurological diagnoses raises serious alarms — especially when so little is known about how the information will be used, or by whom.

Kennedy’s Vow

As secretary of HHS, Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has made autism research a defining priority of his tenure. He presents it not just as a medical challenge, but as a national mission demanding unprecedented scale, speed, and data access.

At a press conference last week, Kennedy emphasized that the investigation will take advantage of a digital transformation in medicine. According to Science,

Kennedy suggested that thanks to “the digitalization of health records and the mass of health records that are now available to us,” efforts to tease out causes of autism can proceed “much more quickly than has ever been done in the past.”

The list of variables to be scrutinized is sweeping: food additives, mold, pesticides, pharmaceuticals, and prenatal ultrasound scanning, as well as parental factors like age, obesity, and diabetes.

The NIH has committed to a “rapid timeline,” though even Bhattacharya now concedes that Kennedy’s original September deadline for results is overly optimistic. Grants may go out by fall, but actual discoveries — if any — will take years, he suggested.

Alternatives to Prying Eyes

There is legitimate public interest in understanding autism’s causes. But such exploration doesn’t require a dragnet approach.

Existing medical literature already offers a vast base of peer-reviewed research into developmental disorders, genetic variants, and neurodivergence. Population studies — using anonymized insurance data or long-running cohorts — can be deepened without pulling millions into a centralized database.

Insights can also come from existing epidemiological analysis, prenatal exposure datasets, and historical vaccination records.

Importantly, none of this needs to run through Washington. The HHS, never envisioned by the Constitution, was not meant to operate a national health-intelligence apparatus. Public health is a state responsibility — local, accountable, and closer to the communities it serves.

Ethical research is possible. It just requires restraint — and respect for boundaries the federal government was never supposed to cross.

Central Intelligence of Health?

In an age when “data is the new oil,” the federal government isn’t just building a database — it’s constructing a pipeline.

Today, it’s framed as autism research. Tomorrow, it could power behavioral profiling, predictive policing, algorithmic insurance denials, or automated eligibility scoring. Health-risk scores may quietly shape credit decisions. Mental-health flags could influence hiring. Fertility histories and step counts might drift into bureaucratic or commercial use.

The NIH insists access is restricted, protections are robust, and intentions are noble. But centralized control over sensitive data rarely stays benign. It expands — quietly, permanently, and often beyond its original scope.

Add to that the administration’s broader effort to integrate federal digital systems — linking medical, financial, and social records — and the direction becomes clear.

“This is a transformative initiative,” Bhattacharya said. Indeed, it is — but not only in the way he ostensibly means. The transformation underway is one in which privacy is optional, consent dissolves into assumption, and public health becomes the gateway drug to centralized governance.