Over a million readers of the Wall Street Journal for October 3, 1985 saw the headline: “Hunts Sell Off Most of Silver Holdings, Taking Losses Estimated at $1 Billion.” The bible of American big business reported under a Dallas dateline that the Hunt silver sales amounted to $350 million, “ending one of the boldest attempts ever to corner the market in precious metals.”

Did the Hunts of Texas actually make an effort to “corner” the silver market? During the last five years, the Wall Street Journal and much of the American mass media have based all their related stories on the assumption that the Hunts sought to corner and manipulate the silver market. The reported $1 billion loss is the presumed price they paid for their failure.

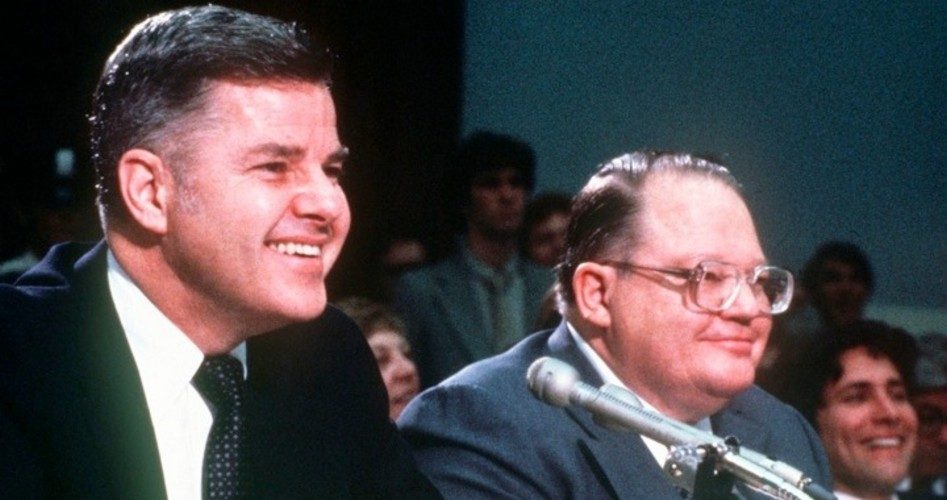

By using such suggestive language as “one of the boldest attempts to corner the market,” etc., what the media and others have implied is that the Hunts operated some sort of conspiracy — that they secretly tried to get control of the entire silver supply and then dramatically drive up its market price. But Nelson Bunker (on the right in the photo) and W. Herbert Hunt (left) were the most conspicuous “cornerers” in the history of the precious metals market. Not only were the brothers bullish on silver during most of the decade of the 1970s when gold was the investment rage, but they were substantial buyers in the open market.

One of the few questions never asked in the last five years has been: Why did the Hunts first buy into what now appears on the surface to be a billion-dollar silver fiasco? The answer is inflation.

Bunker and Herbert Hunt first got into the gamblers’ game of soybean commodity futures in February 1977 as part of their investment strategy to fight inflation. Inflation and food prices are usually linked, and traders in agriculture futures use silver as a hedge, buying silver when soybean and grain prices rise and selling it when the prices fall, to make money to meet future trading obligations.

February 1977 was only one month after Jimmy Carter had been sworn in as president. The Hunts, like a great many other businessmen, assumed that with the Democrats back in the White House, inflation was certain to rage out of control. The double-digit inflation of the Carter years confirmed their worst fears.

Sons of the late H.L. Hunt, who in the 1920s founded the family fortune by winning his first oil lease in a poker game, Bunker and Herbert used their extensive holdings in silver futures as collateral for bank loans to buy 22 million bushels of soybeans at $6 a bushel. Within a month the commodity had jumped to $10, prompting the federal regulatory Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) in Washington to charge that the Hunts’ $96-million profit represented an effort to manipulate and squeeze the market. The CFTC also charged them with violating the 3-million bushel purchase limit on soybean-future contracts by using the names of their various children and family.

The Hunts were furious, insisting they were victims of government rule rigging for the benefit of the Eastern Establishment “insiders” who, they maintained, controlled and manipulated the commodity markets in New York and Chicago for their own advantage.

“There are literally dozens of family ingroups in Chicago if not elsewhere in the country,” fumed Bunker Hunt, “who trade soybeans or trade grains, and the government has never tried to say they are all trading together. I think the reason, frankly, they jumped on us is that we’re sort of a favorite whipping boy, you know. We’re conservatives, and the world is largely socialist and liberal. And, as long as they want to jump on somebody, they want a name and they want to jump on somebody that’s on the other side.”

The evidence of a politically motivated plot to ruin the Hunt brothers is far more substantial than the allegations that they had sought to corner and manipulate either the soybean or silver commodity markets. It is in the area of silver where the evidence of a political plot against the Hunts is substantial.

In the months prior to the October 1973 Middle East war and the Arab oil embargo, the Hunts, because of their Texas oil interests, took more seriously the threats of a Middle East oil embargo than did either President Nixon or his secretary of state, Henry Kissinger. Therefore, they began buying substantial silver futures as a hedge against rising prices that would be inevitable if oil became scarce. By December 1979, the Hunts held commodity futures contracts for between 35 and 50 million troy ounces of silver estimated to be worth somewhere between $600 million and $1 billion.

When they began buying large amounts of silver, the price was less than $3 an ounce, rising by August 1979 to $9 and then spurting by January 17, 1980 to an all-time historic high of $50 an ounce. The price then plummeted back to $10.80 an ounce by March 27, 1980. The Hunt brothers maintain that the dramatic drop in price was due to board members of the established exchanges deliberately selling the market short to break the price.

“All those exchanges are run by the shorts [those who sell short] and with the connivance of the shorts. They knew they could break the market because they were the guys voting,” insisted Bunker Hunt.

The price of silver falling like a rock sent a shock wave throughout the financial world, both in the United States and abroad. What worried just about everyone was that the wild run-up and run-down of silver prices was similar to what had taken place on Wall Street with stocks prior to the 1929 crash. Fear was compounded by an economy in a nervous state, suffering from double-digit inflation and high interest rates which, by the presidential election year of 1980, had become a prime political issue.

Thus the Hunts’ huge accumulation of silver made them prime suspects in an alleged conspiracy to corner and manipulate the silver futures commodity market for enormous profits. Both in the press and before subsequent congressional committees, the Hunts repeatedly denied such allegations. But those denials fell on disbelieving ears. Their case was not helped by the political climate at a time when silver prices roared up to $50 an ounce only to fall back to $10. But other circumstances certainly fueled the prejudicial bias against the Hunts.

First, they were Texas-rich gas and oil men with associations in the Arab world, and Arabs were being blamed for the economic woes of 1980. Double-digit inflation and high interest rates had become a burning political issue that year in the contest between then-President Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan.

Second, not only were the Hunts oil-rich, but they were conservatives who politically and financially supported Republican candidate Ronald Reagan. The four congressional committees that held separate hearings on the wild price fluctuations of silver during the first half of 1980 were all controlled by Democrats.

Third, there had been earlier CFTC allegations that the Hunt brothers had sought to corner the soybean commodity market. Though never substantiated, those allegations left a cloud hanging over the Hunts and their financial dealings.

Fourth, the “silver conspiracy” case seemed to have been clinched when William Bledsoe, a former Hunt employee of 15 years, came forth to tell all about their business dealings, including their heavy involvement in silver. “As I saw it at the time,” he was quoted as saying, “the Hunts were making a concerted attempt to manipulate or control the world’s supply of silver.”

Bledsoe added to the developing melodrama by claiming that Arab oil associates of the Hunts were also deeply involved in trying to corner the world’s silver market. That Arab angle was particularly appealing to architects of the conspiracy scenario since the high inflation and interest rates of the time were being blamed on the greed of the Arab oil-producing states.

Then, in the full glare of news media coverage, came the Hunt brothers’ appearance before congressional committees where they were portrayed as a pair of greedy, insensitive villains.

“I want to make it clear,” Herbert Hunt told a Senate committee in May 1980, speaking also for brother Bunker, “that at no time did I attempt to corner, squeeze, or manipulate the silver market. At no time did I participate in an agreement to corner, squeeze, or manipulate the silver market. At no time did I attempt or agree with others to manipulate the silver market.”

Challenging the conspiracy charge, the two brothers leveled their own allegation that, far from being villains in a conspiracy, they were themselves the victims of one. The dramatic drop in the silver prices, they maintained, was the direct result of decisions made by commodity exchange directors decreeing at the peak $50-an-ounce price that the Hunts could buy silver futures but they could not sell! The CFTC would later admit that “a series of actions prompted by the concerns of the CFTC” drove the price down from its historic high to a level of $10 an ounce within a few days.

The Hunts were, as a result, caught in a nightmarish financial bind: Silver futures in the millions, purchased with hard cash at high prices, were forbidden to be sold as the value of silver skidded in price.

In the U.S. stock market, purchases can be made on the basis of credit. The commodity market compels a speculator to keep on deposit what is known as “margin” — that is, a percentage of the total price of the commodity must be covered in hard cash. What happened in the Hunt case is that the exchange not only suddenly increased margin requirements on silver, but also made these increases retroactive to earlier contracts. Thus the Hunts’ cash expenditures became much greater as the margins they were required to meet were increased.

The upshot was that the brothers, in order to meet their margins, were forced to secure from a bank syndicate what was probably the largest single private loan in recent financial history. The $1.1 billion bank loan, to save them from having to dump their 63 million ounces of silver on a depressed market, required them to put up as collateral just about every income-producing asset they owned individually and as a family.

When the Hunts insisted before a Senate committee that they were not the villains but the victims of a conspiracy, therefore, it was understandable that their claims fell on disbelieving if not deaf congressional ears. But both Bunker and Herbert admitted they had no hard evidence to prove their own charge that commodity exchange directors had deliberately rigged the rules to hurt them.

“I think the market manipulation was very obvious,” Bunker Hunt told the senators, “and I think you can take any market, whether it’s soybeans, corn, cotton … put the same kind of margin requirements to it and … drive it down almost as much as they’ve done with silver.”

But, though the brothers could not prove their charges, neither could the four congressional committees come up with evidence of a Hunt conspiracy. In fact, prior to the May 1980 Senate hearings, the New York Commodity Exchange (Comex) issued a report on the conduct of the Hunts during their five years of dealing in silver futures.

“No evidence was discovered during that period,” the Comex report stated, “which might have suggested a presence of any squeeze, corner, or other attempt to manipulate the silver market and the market was maintained in an orderly fashion and each maturing futures contract liquidated properly.”

Before Bunker and Herbert were questioned by Senate committee members, witness after witness from the commodity industry made two central points: The run-up and then skidding of silver prices did no damage to industry or the economy. Not only did the economy escape damage, but silver brokers were paid all the commissions due, and both brokers and bankers made substantial profits.

One CFTC commissioner told the committee that no firm in industry went under and, like the Hunts, “people all over the world” were scrambling to acquire silver and gold and other items of enduring value rather than place confidence in paper currencies.”

While the Senate committee had been focusing solely on the run-up of silver, and thus ignoring gold, the president of the Chicago Board of Trade, Robert Wilmouth, posed an embarrassing set of facts. According to Wilmouth, throughout history the free market prices of gold and silver have always risen and fallen together. On the day that silver peaked at $50 an ounce, gold had soared to a historic high of $850 an ounce. “Clearly,” he added, “fundamentals were at work — not a market manipulation.”

Oddly, while the Hunts were consistently charged with manipulation of the silver market, the charge of trying to manipulate the gold market was never made! This is puzzling, since all precious metals experienced a run-up in price.

The parallel run-up in the price of gold, silver and platinum was affected, in fact, by an unprecedented constellation of global political and economic circumstances. The following brief chronology illustrates the point:

• August 1979: Chrysler on the brink of financial default.

• August 16, 1979: The Federal Reserve tightens credit.

• September 17, 1979: A Soviet-inspired coup in Afghanistan.

• September 21, 1979: U.S. dollar at its lowest level since 1978.

• November 4, 1979: The President of South Korea is assassinated.

• November 13, 1979: President Carter orders cutoff of oil imports from Iran.

• November 20, 1979: Armed assault on the Grand Mosque in the oil-producing state of Saudi Arabia.

• December 26, 1979: Soviet troops invade Afghanistan.

• January 15, 1980: Soviet troops reported on Iran’s border.

• January 23, 1980: Canadian government raises natural gas price by 30 percent.

These events raised concern about international instability and uncertainty, adding to the fears that inflation and interest rates were going out of control. One of the largest U.S. gold bullion dealers told the Senate committee that when silver reached $40 an ounce, Americans by the thousands flocked to sell silver rings, bracelets, flatware and coins.

“Those ninnies, who lined up 200 deep to sell silver at $40 are today seeing the $12 silver,” Dr. Henry G. Jarecki told the committee, suggesting that the rush helped bring down the price of silver. “I think [it is] the American public … who … made billions of dollars in the rise of the silver price,” he said.

One committee member was not satisfied that certain silver speculators could not bid up the price to artificial levels. “I think,” Dr. Jarecki replied, “that to say someone is trying to do something requires you to get into his mind, and that is very hard.”

The case against the Hunts rested primarily on their vast silver holdings, which their broker told the Senate committee stood at about 39 million ounces between 1979 and 1980. But commodity expert Henry Marigner testified that the combined holdings of the two major commodity exchanges — Comex and the Chicago Board of Trade — amounted to 132.1 million troy ounces of silver. The U.S. government held silver stocks totalling 183.5 million troy ounces! “This hardly supports the allegations of cornering the market,” observed Marigner.

When both Hunt brothers testified, the committee seemed more interested in their extensive business activities than in their motives for investing in silver, asking specific questions about the financial dealings of their more than 150 companies.

“The trouble with those hearings,” Bunker Hunt later said, “is they’re no-win deals. You may not get convicted, but you sure as hell don’t get acquitted either.” Brother Herbert summed up the feelings of the entire family: “I feel like the lady who had her purse snatched and then got arrested for indecent exposure because her clothes were ripped.”

Hounded by the press and pilloried by politicians, the Hunt brothers despite their losses remain resolute. The Hunts are better known now, but out a billion dollars as a result of their ordeal. Bunker, having had his picture taken so much by photographers — whose film requires silver — managed after the Senate hearings to exhibit his usual pluck and down-home Texas humor.

“At least I know,” he quipped, “they’re using a little bit of silver every time they take my picture.”

Photo at top shows W. Herbert (left) and Nelson Bunker Hunt: AP Images

Related article: