With a congressional battle brewing over what is being touted as the biggest attempt at financial regulatory reform since the Great Depression, most pundits are predicting that, despite token Republican opposition, some version of the bill that originated with Senator Chris Dodd’s Finance Committee will soon pass. Senate Republicans blocked the first attempt to bring the matter to a vote on April 19, but Democrats and the Obama administration vowed to continue to press wavering Republicans to support the bill.

“Public sentiment was not working in favor of Republicans, as it did to some extent during the health care debate,” wrote Jim Kuhnhenn of the Associated Press. “Public opinion is leaning toward more regulation of large financial institutions, and a Securities and Exchange Commission lawsuit alleging fraud by Goldman Sachs has added the cloud of scandal to Wall Street.” Meanwhile, Republicans are working hard to ensure that the bill satisfies their own constituencies; any notion of opposing the bill on principle is not given serious consideration. According to Senator Mark Warner (D-Va.), speaking to the Christian Science Monitor, “I’ve never seen a bill that has had more bipartisan input than this legislation. We’re getting closer and closer.”

Public Opinion and Public Policy

Public opinion, ever the refuge of demagogues, is notoriously suspect in times of economic upheaval. Financial shocks like the great contraction of 2008-2009 produce more angst than any other political event besides war, stirring up powerful and often reflexive emotional responses rather than soberly reasoned opinions among the general public. And, just as took place during the depths of the Great Depression, Americans — who are expressing support to pollsters for financial reform — are allowing themselves to be emotionally exploited by politicians of both parties whose real agenda is to strengthen the control of the federal government over the market economy.

The finance reform bill, which has been under preparation in the Senate for months but is only now attracting attention as President Obama and his senatorial allies move it toward passage, differs not a whit in principle from previous attempts by Washington — dating as far back as Teddy Roosevelt’s antitrust legislation, and including the likes of the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933 and the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 — to vanquish various free-market hobgoblins by government regimentation. Although the advantages of the free market over a command economy have been demonstrated over and over, both in theory and in practice, the same pernicious falsehoods about capitalism persist: that it leads to large-scale misallocations of capital, especially the unjust accumulation of wealth in fewer and fewer hands; that it is inherently volatile, leading to periodic panics and recessions; and that it encourages dishonesty and secrecy among the wealthy and powerful. That it is in fact government intervention in the free market that is responsible for such things is not the sort of inconvenient truth that government itself, or its stable of kept journalists in the major news media, is likely to divulge. But the bill now taking shape on Capitol Hill will, as investor and Senate candidate Peter Schiff has recently pointed out, “not only … do nothing to prevent the [next] crisis, it will more than likely increase its severity.”

One of the aims of the new Senate legislation (already in excess of 1,300 pages) is to give the Treasury Department, FDIC, and Federal Reserve so-called “resolution authority” for dealing with the insolvency of mega-financial institutions. The purpose of such an authority is entirely unclear, since arbitration and winding down of the assets of insolvent institutions has traditionally been dealt with in bankruptcy courts. Giving these three government entities new authority to preside over bankruptcy proceedings would involve the executive branch in what has previously been a responsibility of the judicial branch. The motive behind such an executive branch resolution authority — as with much of the rest of the Dodd bill — seems transparent enough, however: the transfer of more power to the executive branch. Such a resolution authority could determine, of course, that a firm in question is too large or systemically important to be allowed to fail, and could give the color of legitimacy to future bailout measures. This, said Senator Richard Shelby (R-Ala.), should not be a permissible outcome. “The message [of this legislation] should be unambiguously that nothing is too big to fail,” the Senator said on Meet the Press.

The bill also provides for the creation of a new regulatory authority, the Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection, which would impose a welter of new burdens on all businesses that offer credit of one sort or another, including installment plans and layaways. The bill’s backers insist that the measure is only intended to target financial companies. But as John Berlau of the Competitive Enterprise Institute pointed out on OpenMarket.org, “The bill’s definition of ‘nonbank financial company’ is so broad that it could cover manufacturers only tangentially involved in extending credit, such as those that lease equipment to their customers. This would raise prices and cost Main Street jobs.” And U.S. Chamber of Commerce President Thomas Donahue, in an op-ed piece for the D.C. political journal The Hill, concurred:

The proposed new consumer protection regulator would be able to regulate a merchant, retailer, doctor, public utility, or any other business that permits payment in more than four installments or assesses late fees. No wonder the first year’s budget for this new regulator is $410 million.

Unlike the Federal Trade Commission or the Securities and Exchange Commission or many other agencies, the proposed Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection would be headed by a single director without a bipartisan commission to provide necessary checks and balances.

Once confirmed by the Senate, this director would report to no one and would have the authority to write and enforce new rules and decide how to spend his or her massive budget. In fact, the budget would automatically increase each year with no oversight by Congress, the president or, for that matter, anyone else.

In other words, this bill — crafted by the powerful and well-connected — will likely end up barely inconveniencing the Wall Street plutocrats it ostensibly targets, and will instead inflict new burdens on Main Street.

Prohibiting Plans to Audit the Fed

One aspect of the Senate finance reform bill that has not attracted any mainstream media attention is its limitations on congressional power over the Federal Reserve. In particular, the bill in its current form would overturn legislation, passed by the House late last year, that would give Congress the power and, indeed, the legal obligation, to audit the Fed. Representative Alan Grayson, a co-author (with Congressman Ron Paul) of House legislation to audit the Fed, told Zero Hedge, a news feed for options traders, that the Senate finance reform bill retains only a few tepid remnants of authority to audit America’s central bank:

The House bill grants the GAO the authority to audit the Fed, and then releases that information to Congress with a six-month delay, to prevent traders from gaming the system.

The Senate version only allows the GAO to audit a certain part of the Federal Reserve, its emergency lending facilities. The GAO already has some of that authority. Amazingly, the Senate version forces the GAO to withhold this information from the public, and Congress, for as long as the Federal Reserve chooses….

The Senate language does not allow audits of the mortgage backed security purchase program, a $1.25 trillion program that at this point comprises the bulk of the Fed’s balance sheet. This program includes Freddie and Fannie backed debt.

The Senate language does not allow audits of possible losses on foreign currency swap lines, of which there were more than $500 billion at the height of the crisis. This includes unlimited credit lines granted to central banks all over the world, solely through at [sic] the discretion of Federal Reserve and without the input of any elected official or the State Department.

The Senate language does not allow audits of open market operations, where there is ample room for errors, market manipulation, and insider trading violations….

In the Senate version, all audits must remain redacted. The GAO can’t even tell Congress to whom the Fed is lending money, the amounts it is lending, or any details about collateral or assets held in connection with any credit facility.

These and similar provisions limiting the power of Congress over the Fed to a few token competencies, are found in section 714 of the Senate bill, entitled “Audit of Financial Institutions Examination Council.” In all likelihood, they constitute the real meat of the Dodd legislation, and may well be a major reason for the sudden urgency with which this bill is being peddled. Last year’s push to give Congress new ascendancy over the Federal Reserve constituted an unacceptable challenge to America’s financial and banking elites, which this bill is intended to answer. The Federal Reserve has managed to survive for almost 100 years because of its — and its backers’ — insistence on absolute secrecy and freedom from any kind of public or private scrutiny. This condition — defended as “independence” — is responsible for public ignorance of the Federal Reserve and how it manipulates the money supply to the advantage of the big banks, the financially well-connected, and, of course, the political class.

Open market operations, for example, are the Fed’s (and other central banks’) major tool for inflating the money supply — yet according to the new Senate finance bill, these operations would remain off limits to congressional scrutiny. So likewise with the operation of foreign currency swap lines, for which greater transparency — one might suppose — would be invaluable to Americans concerned about the eroding value of the dollar. Yet all of the critical operations and so-called assets of the Federal Reserve would remain discreetly shielded from the eyes of Congress and the public, ensuring a continuation of business as usual at the Fed.

Among other provisions in the bill are measures to ensure the future regulatory scrutiny of hedge funds and derivatives trading and to limit the size of commercial bank assets relative to 10 percent of the size of the aggregate of FDIC-insured assets (the so-called “Volcker rule”). Such measures are largely only stopgaps to remedy ills encouraged by previous regulatory “loopholes,” and all of them are directed at the private, not the public sector — despite the fact that malfeasance at the likes of Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae (not to mention the Federal Reserve) were primarily responsible for creating the moral hazard that led to the great asset bubble of the eighties and nineties and its multistage collapse.

The Senate finance reform bill, like its sister legislation already passed by the House, will both consolidate the power of the privileged few over the disenfranchised many and hurl more wrenches into the already grinding cogs of the machinery of the free market. Of all the sophisms in circulation after the collapse of 2008, the most infuriating is the assigning of blame to the free market, when it was in fact government — the Federal Reserve, the Treasury Department, Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, the Community Reinvestment Act and other banking regulations, and so forth — that was and is to blame. If the American people now allow the very government that gave us the Great Recession to assign the blame to the free market, we will ensure that the wolves guarding the sheepfold will continue to have full bellies.

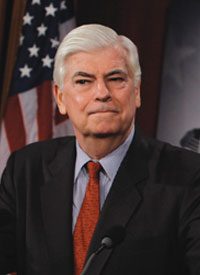

— Photo of Sen. Chris Dodd: AP Images