“The Buck knife saved my leg and maybe my life at least once when I carelessly caught a pant leg in the anchor winch.” So writes “Old Fool,” the retired aviator and mariner who writes a colorful blog on various and sundry things at www.oldfool.org.

“I inherited an old Buck 119 from my grandfather and it saved him a few times in survival situations and myself as well,” declares another Internet testimonial.

Still another states: "I bought my Buck Folding Hunter right out of boot [camp] back in 1960 and carried it through twenty years of Naval service … some of which was pretty rough service. That knife never left my side…. It has saved my life in combat twice."

Most of us, hopefully, will never have to employ a knife in combat or a life-or-death situation, as did Canadian Chris McLellan, when he was attacked by a grizzly bear near Grand Prairie, Alberta, in 2007. Incredibly, McLellan not only survived with relatively minor injuries, but he managed to slay the massive ursus horribilis with his 12-inch-blade hunting knife, the only weapon he was carrying.

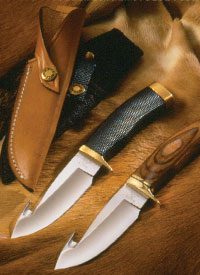

The knife is one of man’s oldest tools, and for those who work outdoors or who spend significant time in outdoor recreational pursuits, this handy instrument — particularly the trusty pocketknife or belt knife — is indispensable. Even cubicle-restricted, keyboard-clanking city dwellers like your editor find it necessary to pull out the pocket blade several times a day, albeit for more mundane tasks, such as opening letters and packages, cutting tape and string, slicing an apple, removing a staple, or tightening a screw. For me, it’s usually the Buck Companion that comes to the rescue, an elegantly slim instrument in a compact two-and-three-quarter-inch body. For bigger ’round-the-garage and ’round-the-yard tasks, it’s usually the Buck Folding Hunter. For hunting, fishing, camping, and hiking, it’s both of the above, plus the Buck Pathfinder, a classic hunting sheath knife with a fixed five-inch blade — and the Buck X-Tract multi-tool.

There are many excellent knives being produced today by quality manufacturers, but none carries the iconic mystique and customer loyalty of Buck. Forged in 107 years of experience and four generations of knife-making tradition and innovation, the Buck name, like its blades, is recognized worldwide and associated with quality, dependability, and integrity. Buck’s famous “Forever Warranty” — and the rugged craftsmanship that backs it up — has set the standard for the industry.

So, one might imagine my excitement and anticipation at touring the new Buck Knives corporate headquarters and manufacturing facility in my home state of Idaho. My guide was none other than CJ Buck, CEO and president of the company and great-grandson of the founder, Hoyt Buck. CJ’s father, Chuck Buck, who serves as chairman of Buck Knives, Inc., had been my tour guide nearly 20 years earlier when I toured the corporate headquarters and manufacturing plant, which was then located in El Cajon, California, next to San Diego. Buck Knives had been a San Diego company since Hoyt Buck opened shop there in conjunction with his son Al in a 10-by-12-foot lean-to after World War II. From these humble beginnings, it had grown and prospered, becoming a near-household brand with worldwide sales. But escalating energy costs, taxes, and regulation, combined with the devastating impact of cheap imports, forced the Bucks to make some tough decisions. If they were going to continue manufacturing their famous knives in the United States, they would have to leave California. They chose Idaho.

From Gem State to Golden State — and Back

The handsome new Buck Knives headquarters and plant looks like a giant hunting lodge, an illusion that is helped by the fact that it is surrounded by beautiful evergreen-covered mountains. It is situated in a new business development nestled between the scenic Spokane River and Interstate-90 in Post Falls, a town of 25,000 that bumps up against Coeur d’Alene, its more famous lakeside resort neighbor to the east. Twenty miles to the west is Spokane, Washington. A hundred miles north is the Canadian border.

The move from California to Idaho is, in a sense, a homecoming, explains CJ Buck, as he leads me, along with my mother and sister Mary Lee, through the Buck family photo gallery and museum. It was in Mountain Home, Idaho, in the 1940s, that Great-grandfather Hoyt Buck actually launched the knife-making business that would become a dynasty. The foundation for it, though, had been laid long even before that, during Hoyt’s boyhood in Kansas. In 1902, Hoyt, then a mere lad of 13, served as a blacksmith’s apprentice. Among his many tasks was sharpening the hoes and other implements of the area’s farmers. Noticing that many of the implements required too-frequent sharpening, and being of inquiring intellect, the young apprentice began experimenting and developed a tempering process that enabled the farmers’ hoes to hold an edge. Hoyt then began experimenting with making knives from files and rasps, something this writer could closely identify with, since I had ground several knives from files with my father when I was around 10 years of age.

Although his formal schooling had stopped after the fourth grade, Hoyt Buck was a self-taught man who read voraciously and continued his education in the school of experience. He headed for the Pacific Northwest and worked at a variety of jobs in the Seattle-Puget Sound area: laborer, insurance salesman, streetcar conductor, boat crewman. While crewing on a boat, he met Daisy Green, daughter of a retired ship captain, whose family came from the wealthy British upper class. They fell in love and married despite opposition from her family, who disapproved of her marrying “beneath her class.”

The young couple struggled financially, but had a happy marriage that was blessed with seven children. When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor in 1941, the Bucks were living in Mountain Home, Idaho, where Hoyt was both a blacksmith and the pastor of the local Assembly of God Church. Faced with a shortage of knives for our servicemen, the U.S. Government asked Americans to donate their fixed-blade knives. Hoyt Buck responded by turning out a steady supply of hand-ground knives that quickly won the admiration of many G.I.s. After the war, many returning soldiers, sailors, and Marines wanted the dependable “Buck Knife” for civilian use. Unable to keep up with the demand, Hoyt and Daisy moved to San Diego, where their oldest son, Al, had settled, and set up shop on the side of Al’s garage.

Before succumbing to cancer in 1949, Hoyt Buck could take comfort in the knowledge that he had passed on his knife-making skills to his son Al. Buck Knives, Inc. began with a product lineup of six fixed-blade hunting knives. In order to kick-start their business to a new level, Al and his wife, Ida, set out on a cross-country road trip, making personal sales calls on some 250 sporting-goods stores and hardware stores. At a time when most sport knives sold for around $2, the Buck models were priced five to 10 times higher. But Al was convinced people would be willing to pay more for quality steel, superior workmanship, and a revolutionary, iron-clad guarantee to repair or replace any Buck knife that failed due to any manufacturing deficiency. Shop owners were impressed not only with the quality of the product and the unprecedented warranty, but also by the fact that the president of the company came personally to see them and to express his commitment to stand behind his product.

Tradition and Innovation

The Buck Model #110 Folding Hunter, debuting in 1964, was the product that put Buck Knives “on the map.” A few other folding knives with four-inch blades were on the market, but none met the quality standards of Buck. After considerable experimentation, Buck came up with the now-classic model that met the company’s high standards for both functional and aesthetic appeal. The Folding Hunter became an instant hit with sporting consumers and remains a top seller. It also became one of the most widely imitated knives.

It is this commitment to traditional quality and cutting-edge innovation that continues to propel the company, says CJ Buck. Today, Buck Knives boasts a product line that includes 225 knife models and variations utilizing a broad array of complex steel alloy blades, with handles made from materials ranging from giraffe bone to space-age thermoplastics. But innovation doesn’t mean merely new alloys, knife designs, and marketing plans. “We realized that if we intended to stay in business and manufacture our own knives with the quality we insisted on, that moving from California alone would not be sufficient,” CJ told us as we toured the plant. “We also had to implement very lean manufacturing processes that would shave every penny possible off the cost of production.” The Buck plant in Post Falls is a marvel of simplicity and efficiency, where 205 employees turned out over one million knives in 2008.

“This facility is physically 30 percent smaller than our California plant was, but we are more productive, have far greater cost efficiency, and are a lot more flexible,” Buck explains. “We try to make sure that there is no wasted motion, no wasted energy, no wasted time, and no wasted materials.”

Most of the knives are pressed into their initial shapes, called blanks, from long rolls of coil steel fed into fine blanking presses. But CJ points out that Buck also creates blanks through laser cutting. The laser machines do not require tooling so it is possible to make production design performance improvements in hours instead of weeks or months waiting for new fineblank tooling. The lasers also open up opportunities for special-order blades and exotic blade steels that are too hard to fine blank. Being fast and flexible is also key to being consistent in shipping on time every time. A big part of the lean manufacturing cost-efficiency is maintaining a low, as-needed inventory. However, you don’t want wholesale or retail customers to be kept waiting, or you’ll lose sales. Buck prides itself on its nimble response and quick turn-around time, another company trait that has paid off in customer loyalty.

As a result of their increased production efficiency, Buck Knives announced earlier this year it was bringing back more of its production from China. The 2005 move to Idaho actually involved a two-year transition plan, which required shifting about 50 percent of the company’s production to China. It is now down to about 25 percent, and should continue to drop. CJ Buck acknowledges that the China decision didn’t set well with many of Buck’s loyal customers. “We’ve always been a ‘Made in the USA’ company, and we think that we’re showing we can be viable and keep manufacturing here in America,” he says.

At the heart of good knife-making is the art and science of heat treating. “When my Great-grandfather Hoyt heat treated steel, he knew he had achieved the correct temperature in the steel when it was the color of butter just before it melts,” CJ explained. “He knew from experience when to remove the blade from heat for the best balance between hard enough to hold a good edge and tough, non-brittle enough to take a beating without cracking.” Today, heat treating is a “far more sophisticated and controlled process” in contrast to Hoyt’s approach. The blades at the Buck Knives factory are tempered as they travel through the heat-treating ovens on conveyor belts. Each blade type and alloy requires a different temperature setting and a different length of furnace time, measures that are closely guarded trade secrets. Just as important as the heating is the cooling process, which is rigorously monitored.

And when it comes to heat-treating blades, many would consider us remiss if we did not mention the foremost name in the business: Paul Bos Heat Treating. Paul Bos, who heat-treats blades for many of America’s top custom makers, has had a long relationship with Buck Knives. In fact, he operates out of a shop at 660 S. Lochsa Street in Post Falls — which just happens to be the same address as Buck Knives.

God, America — and Buck Knives

From its start, the Buck family’s Christian faith has been an integral part of the business. Although Hoyt left his pastoral ministry to found his family knife business, three of his sons — George, Roland, and Walt — graduated from Northwest Bible College and went into full-time ministry. Chuck Buck, Hoyt’s grandson and CJ’s father, is chairman of the company today, and is as well known in some Evangelical Christian circles as he is in sportsmen’s circles. Chuck is a graduate of Southern California Bible College (now Vanguard University) in Costa Mesa and is active in supporting a number of Christian ministries. The Buck Knives website carries this message from the late Al Buck:

From the beginning, management determined to make God the Senior Partner. In a crisis, the problem was turned over to Him, and He hasn’t failed to help us with the answer. Each product must reflect the integrity of management, including our Senior Partner. If sometimes we fail on our end, because we are human, we find it imperative to do our utmost to make it right. Of course, to us, besides being Senior Partner, He is our Heavenly Father also; and it’s a great blessing to us to have this security in these troubled times. If any of you are troubled or perplexed and looking for answers, may we invite you to look to Him, for God loves you.

“For God so loved the world that he gave His only begotten son; that whoever believeth in Him should not perish, but have everlasting life.” John: 3:16

Buck Knives is the quintessential American success story, exemplifying the entrepreneurial virtues of pluck, tenacity, ingenuity, integrity, and faith. “To keep the business in the family for three or four generations is becoming very rare,” says Daniel Van Der Vliet, director of the Vermont Family Business Initiative at the University of Vermont. Van Der Vliet estimates that only about three percent of family-owned businesses now reach their fourth generation. Chuck Buck believes the Almighty has had a hand in that. When asked in a 2006 interview why Buck Knives continues to be such a respected brand, he didn’t offer a definitive silver-bullet answer.

“I’ve thought quite a bit about why our name is so strong in the marketplace,” he said. “I don’t have a good answer for why. We know we have to come out with outstanding products every year. [And] I know the Lord has blessed us for honoring Him.”