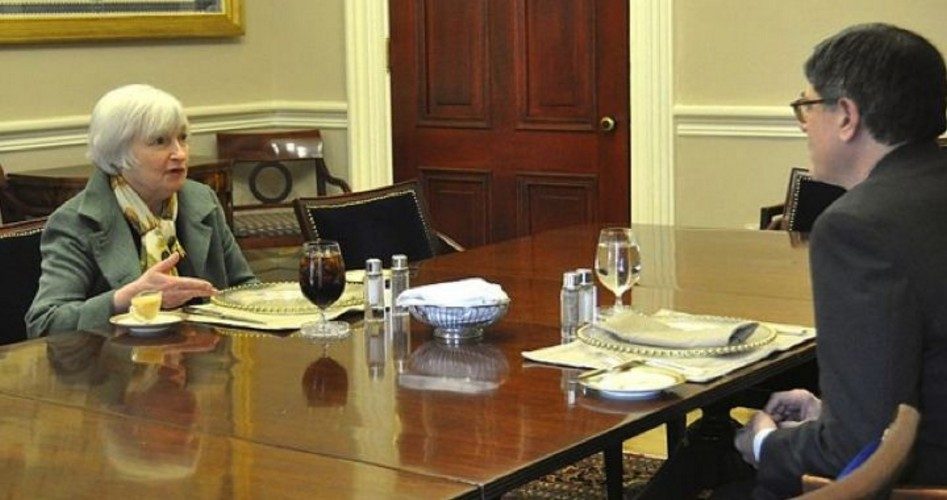

Federal Reserve Chairman Janet Yellen (shown on left) faced unusually stiff grilling from Republicans in the House Financial Services Committee this week.

The committee chairman, Representative Jeb Hensarling (R-Texas) told Yellen that the Federal Reserve and the Obama administration have both failed with the nation’s economy in the seven years since the deep recession of 2007-2009. “What is clear and verifiable is that this weak economy doesn’t work for millions of Americans. The Fed has been the facilitator and accomodator of the administration’s disastrous national debt policy and has regrettably lent its shrinking credibility to advancing the administration’s social agenda.”

Yellen’s appearance before the committee has come at a time when many in Congress and in the nation as a whole are increasingly bothered by the role the Fed plays in the overall economy. And many are advocating that it is time that Congress provide more oversight of the central bank’s governance.

Representative Scott Garrett (R-N.J.) added his own criticism. “Having Congress oversee your agency more thoroughly will not make it more political than it already is.” Garrett provided examples of what he said were the Democratic Party bias of the Fed, including a speech that Yellen gave only two weeks prior to the mid-term elections in 2014, decrying “income inequality” in the country. That buttressed a campaign theme the Democrats were making at the time.

“Two weeks before an election, you’re making political statements consistent with the Democrat Party,” added Representative Sean Duffy (R-Wis.), “I hear you taking a Democrat line.”

Yellen refused to even concede that the Democrats were making income “inequality” a major them in the 2014 elections. Yet, Yellen said, “When we over the last 25 or 30 years realize that income inequality is increasing, and it’s been an inexorable rise, that’s really a concern.”

Predictably, Democrats on the committee defended Yellen, arguing that unemployment has fallen from nearly 10 percent to less than five percent since the Great Recession. Yellen contended that the economic recovery has been due to the Fed keeping interest rates low so as to boost the creation of jobs. Yellen told the committee that she is very cautious about hiking interest rates, in the face of too little investment spending.

The Fed left a key interest rate unchanged at a low level of 0.25 percent to 0.5 percent at its recent meeting, last week. The Fed has three principal ways to change the money supply, all of which can affect interest rates. With the reserve requirement, the Fed dictates to banks what percentage of a deposit can be loaned out; open market operations consist of the buying and selling of government securities in the bond market; and by making loans to member banks at an interest rate — the discount rate — determined by the Fed.

Republicans in the House have legislation to require the Fed to adopt a formula under which inflation (by which they mean the general price level) and other measures would guide its decisions concerning interest rates. Yellen opposes the plan, dismissing it as “unworkable,” preferring the present situation in which there are no controls upon the central bank’s decisions. Yellen is particularly concerned about a Republican proposal that would give congressional auditors the chance to review decisions made by the Fed on interest-rate policies, because that would restrict the historic independence of the Fed to set monetary policy.

And the Fed has been using that “independence” to push interest rates lower, most recently by expanding its balance sheet by more than four times to $4.5 trillion in the purchase of government bonds.

The argument for lower interest rates is that consumers and business will borrow more money at lower rates, thus “expanding the economy.” But this manipulation of the interest rates by the Fed is basically another form of government price controls — in this case, the price of money — with the predictable bad results.

Holding interest rates below the free market price distorts the economy. More money is borrowed than would otherwise be the case, causing a “boom,” which is followed by an inevitable bust, or recession, and sometimes even a depression. Prices are a signal to consumers. Whenever a price is low, one has more buyers than what one would have at a higher price. The problem is that interest rates set by Fed policy below the free market level causes producers to mistakenly believe there is more “demand” than there actually is. This leads to what is termed “malinvestment,” or investment in the wrong things, and an eventual crash. It also transfers wealth from those whose savings earn below market interest rates to those who are borrowing at below market interest rates.

Former Texas Congressman Ron Paul explained this expertly in his book End the Fed. “When central banks push down rates on a whim, the impression is created the savings are there when they are in fact completely absent. The resulting bust becomes inevitable as goods that come to production can’t be purchased, and reality sets in by waves. Businesses fail, homes are foreclosed upon, and people bail out of stocks or whatever is the fashionable investment of the day.”

Paul added, “Tyranny always goes hand in hand with government’s wrecking of the money system.”

The Founding Fathers gave Congress the power to set the value of the money it issues in the Constitution, but in 1913, Congress delegated that power to the Federal Reserve System (an action many opponents of the Fed contend was an unconstitutional delegation of power by Congress). Economist Hans Sennholz believes this was “the most tragic blunder ever committed by Congress.”

Why did Congress do such a thing? After the banking Panic of 1907, Senator Nelson Aldrich (the maternal grandfather of liberal Republican Nelson Rockefeller) was appointed to head up the National Monetary Commission. Aldrich consulted international bankers and the heads of the European central banks to develop a plan for a similar public-private bank system for America.

In late 1910, many powerful figures met secretly at Jekyll Island off the coast of Georgia to construct the plan for what would become America’s central bank — the Federal Reserve System. Because there was much historic opposition to centralizing of banking in the United States (Thomas Jefferson and Andrew Jackson had been fierce opponents of the First and Second Banks of the United States, which were central banks that existed for a time in the early part of the 19th century), international banker Paul Warburg suggested selling the bankers’ central-bank plan as a “federal” system, with branches spread across the country.

Problems developed, however, when Republican President William Howard Taft opposed the proposed central bank. This precipitated a challenge to his renomination by the Republican Party in 1912, led by former President Theodore Roosevelt. Taft beat back the Roosevelt challenge for the Republican nod, but Roosevelt then launched a third-party “Progressive Party” bid, heavily financed by banking interests that favored a central bank.

In America’s 60 Families, Ferdinand Lundberg told what happened. “Throughout the three-cornered fight [Taft-Roosevelt-Wilson] Roosevelt had [Morgan agents Frank] Munsey and [George] Perkins constantly at his heels, supplying money, going over his speeches, bringing people from Wall Street in to help.”

Lundberg noted that “Perkins and J.P. Morgan and Company were the substance of the Progressive Party.” J. Pierpont Morgan was perhaps the most powerful banker in America at the time. New Jersey Governor Woodrow Wilson, on the other hand, was also supported by banking interests, specifically Morgan. With the Republican Party split between Taft and Roosevelt, Wilson won the presidential election.

Wilson proceeded to support the passage of the work of the men who clandestinely met at Jekyll Island two years earlier, and won passage of the Federal Reserve bill in late 1913. Today, most Americans little question the Fed, and assume that the country has to have such a system of printing of a fiat currency.

Ron Paul explained: “Part of the public relations game played by the chairman of the Fed is designed to suggest that the Fed is an essential part of our system, one we cannot do without. In fact, the Fed came about during a period of our nation’s history called the Progressive Era, when the income tax and many new government institutions were created. It was a time in which business in general became infatuated with the idea of forming cartels as a way of protecting profits and socializing losses.”

A return to the gold standard is part of the solution that Paul mentions in his book. Rather than depend on hoping the governors of the Federal Reserve will show restraint in the Fed’s monetary policy, he advocates tying American money to gold, as was done in the 1800s, as a preferable path.

Paul was part of the U.S. Gold Commission, which delivered its final report during the early years of the Ronald Reagan presidency. On a helicopter flight to Andrews Air Force Base, Reagan told Paul, “Ron, no great nation that abandoned the gold standard has remained a great nation.” But Reagan was swayed by his staff, Paul lamented, to not push the idea of America returning to the gold standard. “His advisers successfully kept him quiet on this issue, fearing that he would be seen as crazy or kooky.”

While it is a hopeful sign that some Republicans in Congress are challenging the policies of the Fed, and even pushing for an audit of the banking monopoly that the Fed is, Paul and others would argue that stronger medicine is needed. “Ending the Fed would be the single greatest step we could take to restoring American prosperity and freedom and guaranteeing that they both have a future,” Paul contends.

Thomas Paine, who achieved fame with his pamphlet Common Sense, in which he argued it was “common sense” that an island (Great Britain) cannot rule a continent (North America), was an opponent of fiat paper money — such as the Federal Reserve “notes” issued by the Fed. “As to the assumed authority of any assembly in making paper money, or paper of any kind, a legal tender, or in other language, a compulsive payment, it is a most presumptuous attempt at arbitrary power. There can be no such power in a republican government: the people have not freedom — and property no security — where this practice can be acted.”

In vetoing the re-charter bill for the Second Bank of the United States in 1832, President Andrew Jackson explained how that central bank of his day was incompatible with republican government. “It is to be regretted that the rich and powerful too often bend the acts of government to their selfish purposes. Distinctions in society will always exist under every just government. Equality of talents, of education, or of wealth can not be produced by human institutions. In the full enjoyment of the gifts of Heaven and the fruits of superior industry, economy, and virtue, every man is equally entitled to protection by law; but when the laws undertake to add to these natural and just advantages artificial distinctions, to grant titles, gratuities, and exclusive privileges, to make the rich richer and the potent more powerful, the humble members of society-the farmers, mechanics, and laborers-who have neither the time nor the means of securing like favors to themselves, have a right to complain of the injustice of their Government. There are no necessary evils in government. Its evils exist only in its abuses. If it would confine itself to equal protection, and, as Heaven does its rains, shower its favors alike on the high and the low, the rich and the poor, it would be an unqualified blessing. In the act before me there seems to be a wide and unnecessary departure from these just principles.”

When the First Bank and the Second Bank were chartered by Congress in 1791, and 1816, respectively, they were given 20-year charters. Unfortunately, when Congress created the Federal Reserve System in 1913, the banking elites had learned their lesson. They were not going to allow some president of the United States, such as Jackson, to spoil their work by vetoing the extension of its life. Now, it will take a majority of both houses of Congress to perform the patriotic act of ending the Fed. Then, it will take a president in the White House who is willing to sign the legislation.

If that were to happen, Republicans will no longer need to worry about some chairman of the Federal Reserve using her powerful position to advance the political fortunes of the Democrats — because their would be no chairman of the Fed.

Steve Byas is a professor of history at Randall University.