In a misleading article by Associated Press that IOUs “stashed away” in an investment account in Parkersburg, West Virginia, were going to have to be sold to meet Social Security shortfalls, all the attention was on the location of the account instead of what was in it.

Analyzed here and elsewhere, Social Security is now suffering in the open as a result of unconstitutional and unsound financial assumptions starting in 1935. First of all, the gigantic welfare program, the largest government transfer program in the world, was sold to the American people during the Great Depression as an annuity guaranteed by the federal government. In fact, it still retains the early efforts to link Social Security to the insurance industry (which, at that time, still retained a high degree of public trust) by calling it the Federal Insurance Contributions Act, or FICA. However, a Supreme Court ruling in 1960 not only upheld the Constitutionality of a section of the original law that gave Congress the power to amend and revise the schedule of benefits, but denied that the act created an enforceable contract between participants and the United States government and that, consequently, payments from Social Security are not property rights and therefore are not guaranteed after all.

Secondly, the act was a government intervention into the private lives of those who had failed to provide sufficiently for themselves that was never envisioned by the founders.

Thirdly, despite the fact that Social Security is a Ponzi scheme on a massive scale, it’s faulty and misleading economic calculations were never exposed to the light of day since so many more taxpayers were paying into the scheme than those who were taking out. In the very beginning, there were nearly 40 taxpayers supporting the system for every one receiving benefits. As Social Security benefits were expanded over time and to include Medicare and prescription coverage, it became increasingly clear that the entire system was one day going to run out of money.

Last year’s Trustees Report Summary said, “The financial condition of the Social Security and Medicare programs remains challenging. Projected long term program costs are not sustainable…and deficits will [have to be] made up by redeeming trust fund assets.” Although there is a relatively small balance in the programs accounts, “growing annual deficits are projected to exhaust [them]” in less than seven years. In order to keep this program going, according to the Trustees, shortfalls “will continue to require general revenue financing and [additional taxes] that [will] grow substantially faster than the economy and beneficiar[ies]’ incomes over time.”

Medicare is in such poor shape, and has failed so much faster than its larger kin, that general tax revenues “will soon account for more than 45 percent of Medicare’s outlays.” In fact, “it is expected that about one quarter of Part B enrollees will be subject to unusually large premium increases in the next two years [just to keep the program going].”

In other words, the game is up. Hudson Institute noted that a previous report from Social Security had estimated that the programs wouldn’t “go negative” until at least 2019, but the Great Recession has so severely reduced tax revenues that $29 billion of that “nest egg” will have to be sold just to pay the beneficiaries this year. An advocate to keep Social Security and Medicare going, Mary Johnson with The Senior Citizens League, said, “This [beginning liquidation of reserves] is not just a wake-up call, this is it. We’re here. We are not going to be able to put it off any more.”

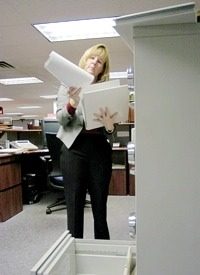

What is this “nest egg”, anyway? Locked away in the bottom drawer of a desk in a government building in Parkersburg is a three-ring binder containing special government bonds that are payable to the Social Security program. There are about $2.5 trillion of these bonds in this binder, representing a claim on the “full faith and credit of the United States of America.” In fact, according to Barbara Kennelly, president of the National Committee to Preserve Social Security and Medicare, “[Those bonds are just] as solid as what we owe China and Japan.”

In other words, the money is gone. It’s been spent by Congress, and in its place are pieces of paper representing more promises to pay. And the fact that they are “just as solid as what we owe” to China, Japan and others should give retirees or potential beneficiaries small comfort. As Gary North and Bill Clinton have said, perhaps the only time they ever agreed on anything, there are only three ways out of this mess: raise taxes, reduce benefits, or go private.

The Cato Institute has been looking into the “private” option for a number of years, and Michael Tanner just asked: "Could it be time to put Social Security reform back on the table?”

He points out that, at present, Social Security and Medicare account for 23 percent of the federal budget, and that nearly 80 percent of Americans pay more in Social Security taxes than they do income taxes. He also points out that “the program is unsustainable…the trust fund contains no actual assets…the bonds are simply a form of IOU…it says nothing about where the government will get the money to pay back those IOUs. "Overall,” he says, “the amount the [Social Security] system has promised beyond what it can actually pay now totals $17.5 trillion. Yes, that’s trillion with a T.”

And workers, as pointed out above, “have no ownership of their benefits.”

Tanner said the program could be fixed but it would take a doubling of the current payroll tax, or benefits would have to be cut by at least 25 percent. And, he said, raising taxes “will do nothing to fix the fundamental problems of ownership, inheritability and choice.” To say nothing of the programs’ inherent fraud and unconstitutionality.

The only workable solution, says Tanner, is to “allow younger workers to invest privately a portion of their Social Security taxes through personal accounts so as to take advantage of the higher returns earned through investment in real assets [which would] offset the reduction in government benefits that will be required to [keep the system solvent].”

Commenting on the “lost decade” of poor investment performance in stocks, he points out that if workers retiring today “had been allowed to start privately investing their taxes 40 years ago…they would still have more than Social Security promises. "Remember,” he added, “someone retiring today would have begun contributing to his or her retirement account 40 years ago, when the Dow was at less than 1,000.” According to a survey taken in 2009 by Sun Life Financial at the bottom of the market, 48 percent of Americans would opt out of Social Security even if doing so meant the loss of all future Social Security benefits. And among workers under age 30, the number wanting out of Social Security was an amazing 59 percent.

Tanner may be right. The nest egg is cracked. But maybe Humpty Dumpty can be put back together again. At the very least, it’s worth considering.

Photo: Susan Chapman, director of the Division of Federal Investments, at the Treasury Department’s Bureau of Public Debt offices in Parkersburg, W.Va.: AP Images