One of the key talking points of the Left revolves around the Obama administration ushering in an era of fiscal restraint, pointing to four consecutive years of shrinking deficits as evidence of federal budgetary discipline. If civilian employment is a barometer, however, the era of “big government” is not only alive and well, but the monster is growing larger by the day.

The Federal Civilian Workforce Is Growing

After initial restraint due to the aftereffects of 2013’s budget sequestration, the federal civilian payroll is on the rise. After bottoming out in May 2014 at 2.726 million workers, the workforce has been growing, with agencies adding 41,000 to their payrolls in the last year alone. The figure now stands at 2.79 million, the highest total of the Obama presidency.

As with the private sector, the government adds employees as needed to manage growth. To be fair, government growth has been flat since 2009, with outlays hovering between $3.5 trillion and $3.7 trillion. Is fiscal restraint expected to continue?

According to the White House’s own projections, it is not. The 2016 federal expenditures are estimated to surpass $3.95 trillion — a seven-percent increase — and are projected to increase between four and seven percent through 2021. Meanwhile, gross domestic product is stuck in neutral, meaning the government is all but certain to grow much more quickly than the economy into the next decade.

The recipe of slower revenue growth and faster government spending portends larger budget deficits. The projected deficit for 2016 is $615.8 million, a 40-percent increase over the prior year.

How do deficits threaten the economy?

Budget Deficits

The United States has had a long history of budget deficits, with only 12 out of the last 76 years showing surpluses. The inability of the government to balance its books is so pervasive that red ink is considered normal. Dick Cheney once famously declared, “Reagan proved deficits don’t matter.”

And yet they do. Deficits pile more dollars onto the national debt, which stands at $19.4 trillion and counting. Interest expense on the debt was six percent of the federal budget in 2015 — a number that while significant, has been held down by historically low interest rates. Despite the Federal Reserve’s reluctance to raise rates, eventually it has to happen, and when it does, that percentage will grow.

What happens if it does? Business reporter-turned-novelist Alex Berenson explains as follows:

To finance deficits, the government must sell bonds to investors, competing for capital that could otherwise be used to invest in stocks or corporate bonds. Government borrowings raise long-term interest rates, stifling economic growth.

Ron Paul put it another way, indicting politicians who tolerate fiscal irresponsibility in the process:

Deficits mean future tax increases, pure and simple. Deficit spending should be viewed as a tax on future generations, and politicians who create deficits should be exposed as tax hikers.

Despite the belief by many that deficits “don’t matter,” they are effectively a cancer upon the finances of the country. Deficits cause the national debt to grow insidiously, sapping the underlying strength of the economy in the process.

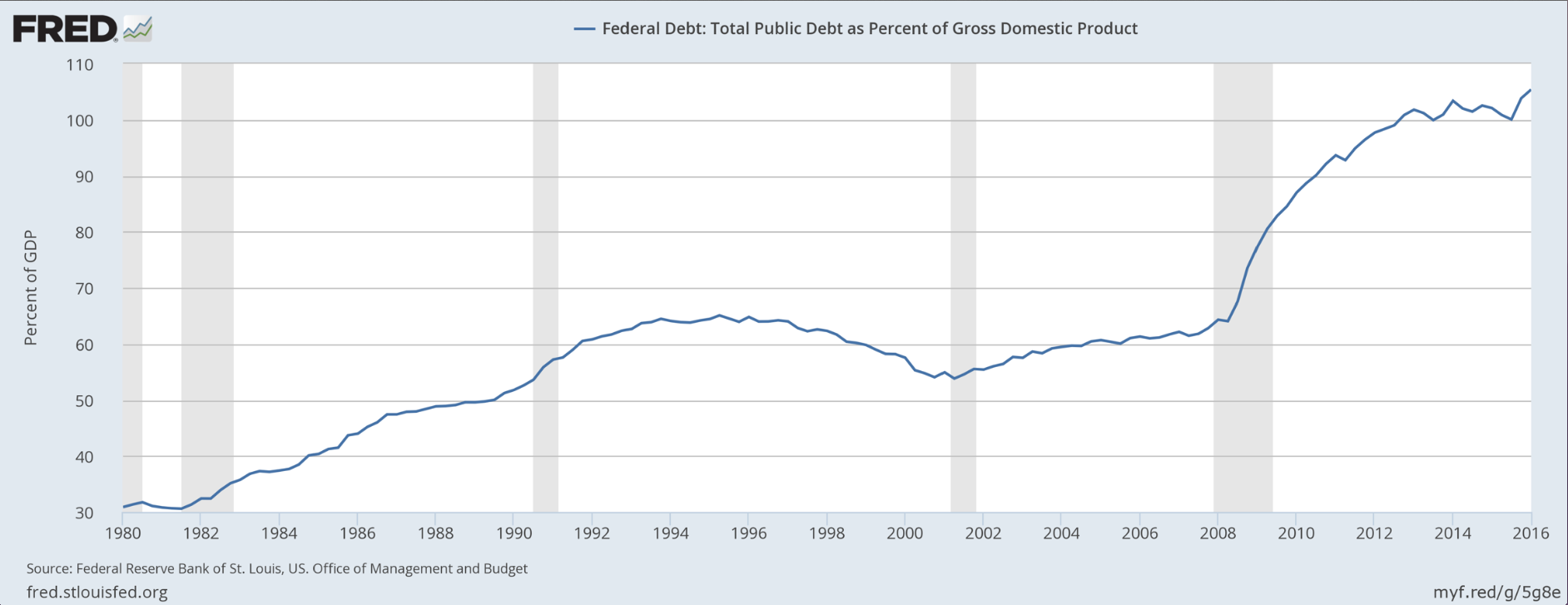

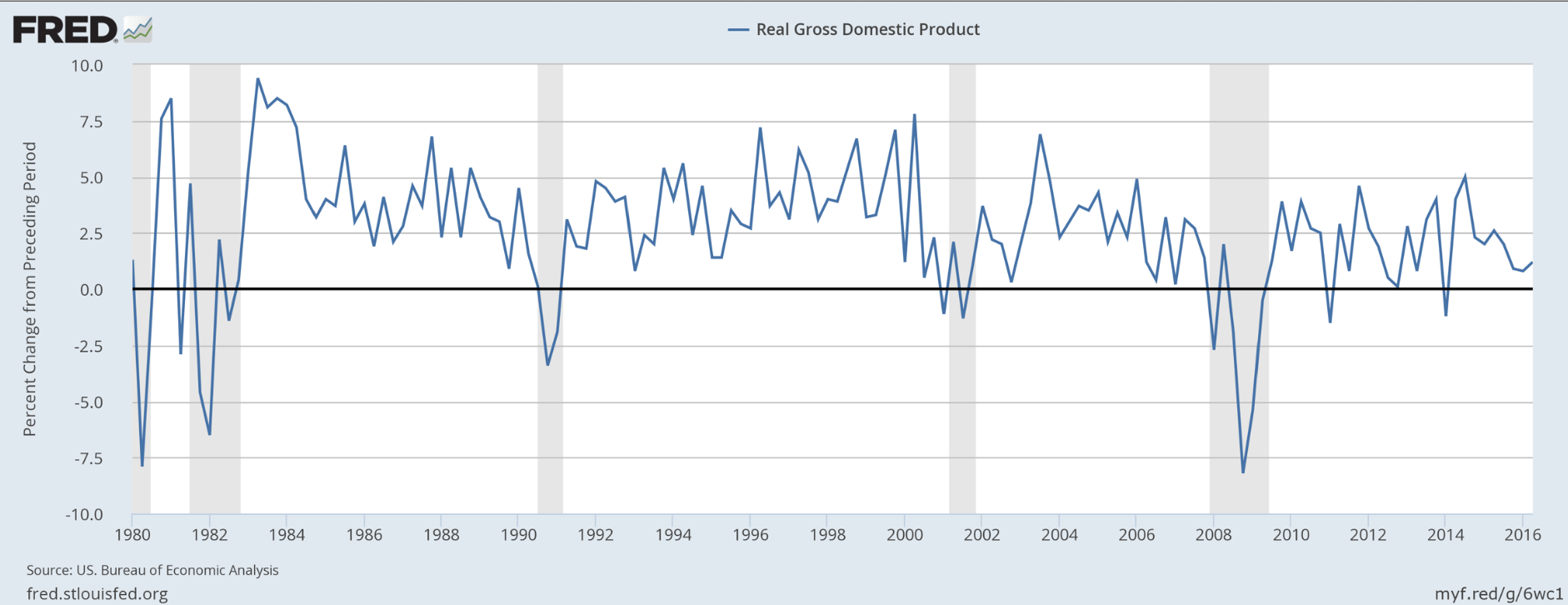

But it’s more than just that. An argument can be made that as deficits have added to the national debt, the long-term trajectory of GDP growth has suffered in concert. Consider the following two charts:

In the first chart, the national debt as a percentage of GDP has risen steadily since 1980, spiking to new highs over the past seven years. In the second, gross domestic product generally grew more quickly (when not in recession) during the ’80s and ’90s than it has over the past 20 years.

Coincidence? There are a myriad of factors influencing both charts, but it’s clear that the lack of fiscal discipline is one significant reason why the economy has been unable to sustain even average levels of growth in recent decades.

The Solution: It’s in the Constitution

Alexander Hamilton wrote the following dissertation regarding the relationship between the states and the federal government:

The definition of a confederate republic seems simply to be “an assemblage of societies,” or an association of two or more states into one state. The extent, modifications, and objects of the federal authority are mere matters of discretion. So long as the separate organization of the members be not abolished; so long as it exists, by a constitutional necessity, for local purposes; though it should be in perfect subordination to the general authority of the union, it would still be, in fact and in theory, an association of states, or a confederacy. The proposed Constitution, so far from implying an abolition of the State governments, makes them constituent parts of the national sovereignty, by allowing them a direct representation in the Senate, and leaves in their possession certain exclusive and very important portions of sovereign power. This fully corresponds, in every rational import of the terms, with the idea of a federal government.

Hamilton believed that although the federal government played an obviously key role in the republic, of critical importance were state governments. Along with John Jay and James Madison, he helped pen a series of 85 essays (known as The Federalist Papers) in support of the Constitution.

Were he alive today, Hamilton would be appalled at the massive growth of the federal government — a trajectory that projects to increase following the rise in the workforce as discussed above. In order to resolve the debt-and-deficit crisis facing this country, federal excesses must end and more rights and responsibilities must be vested back to where they belong: the states.

Perhaps Hamilton put it best when he declared, “In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place, oblige it to control itself.”