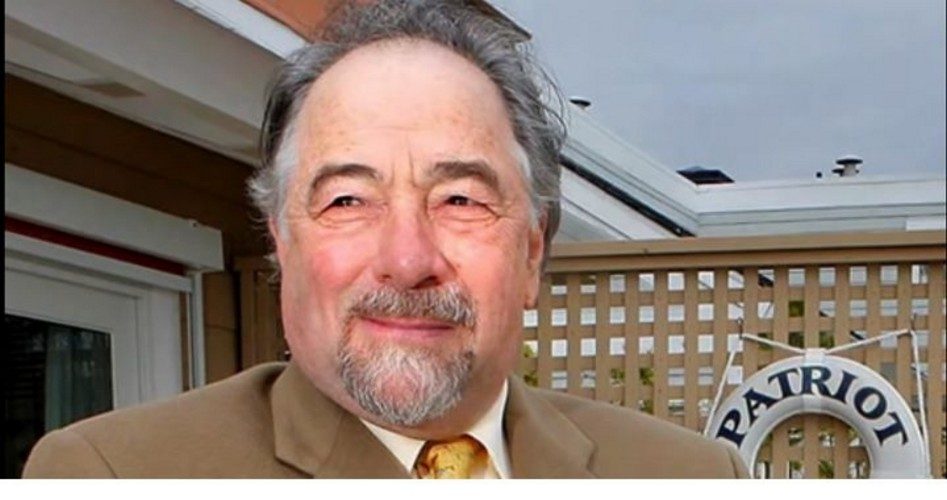

What if a family doesn’t “have the money for that second or third child?” asked radio host Michael Savage recently. “Is that not a justifiable situation for an abortion?” It was a question the talk giant posed to his audience last Friday after the March for Life in Washington, D.C. And it certainly warrants examination.

It was a sincere question. Savage spent most of the segment speaking glowingly of the march and one of its star speakers, Congresswoman Mia Love (R-Utah). He also contrasted the virtue displayed during the event with the vice-ridden and vile “Women’s March” the previous week. Yet Savage also cautioned against going too far in outlawing prenatal infanticide. Here was his question, edited just slightly for brevity:

How would you justify a family that has one child, and they have limited income, and they can raise that child in … a middle-class way? And then the woman becomes pregnant, and they can’t afford that second child’s medical care, clothing, housing, education. And they know that if they have that child, the first child will live not so much as a middle class child, but will fall into a lower category in society.… Is that not a justifiable situation for an abortion?

Savage warned against returning to the dark ages of the 1940s and ‘50s, which, he said, were a terrible time for women (video below). He was referring to illegal, “back-alley” prenatal infanticide, which did at times leave women injured or even dead.

Savage certainly was right about one thing. He stated, “I would wager a bet that there are only a few people in my audience who have not been touched by abortion.” I myself can’t claim to be one of those few. You see, my paternal grandfather was a physician who performed illegal prenatal infanticide.

The story goes that he, like Savage, was concerned about women dying at the hands of back-alley, prenatal-infanticide butchers; being a doctor, he could perform the procedure safely (at least as far as the woman went). And while I never knew my grandfather, I have every reason to believe that he, like Savage, was sincere. He was also sincerely wrong.

The answer to Savage’s question lies in his own phraseology: He didn’t say the parents can’t afford that second unviable tissue mass, nor would he. He said that “they can’t afford that second child.” (Emphasis added.)

You can’t murder one of your children.

While inveighing against eugenics, G.K. Chesterton wrote, “Let all the babies be born; and then let us drown those we do not like.” His point was that having to look the victim in the face brings us face to face with our actions’ true nature. The stoic ancient Spartans could do this, mind you, as they killed newborn babies they perceived imperfect.

Post-natal infanticide is always more honest than prenatal infanticide. Of course, we prefer the latter because it provides emotional distance from the reality of our actions. It’s reminiscent of a high-school class I had in which the teacher asked: If you could push a button and you’d get a million dollars, but an old man in China without a family would die, would you do it? Approximately a third of my classmates raised their hands indicating they would.

The reality is that Savage’s hypothetical parents already have two children, and allowing the second to be born actually offers an advantage: They could then choose which one to kill. After all, how can we know the first really is preferable to the second?

The main advantage the first enjoys is that his parents are more emotionally bonded with him than with his unborn sibling. Allowing that sibling’s birth would level the playing field, enabling the parents to do a better cost-benefit analysis. Maybe the first is an annoying, troublesome brat.

Related to this, Savage has often spoken movingly of his mentally handicapped brother’s plight. He was taken from Savage’s family, if my memory serves, much for the same reason as in Savage’s hypothetical — doctors told Savage’s parents that the brother’s presence would negatively affect the other child(ren).

Not only is there this uncanny similarity between the argument Savage made for tearing a baby from the womb and the one that tore his family apart, but the reality is that when a society accepts the principle of killing the burdensome, people such as his brother are always the first to go.

In fact, the moral solution for a family that can’t handle the burden of a child — offering him for adoption — is much more easily effected with a healthy baby who simply poses a financial strain than with one who’ll need special care his entire life.

Whatever the case, though, how would the remaining child feel upon learning that his brother was killed so he could live a better lifestyle? Moreover, how good a mother will he have after she has experienced the emotional trauma of having murdered one of her own babies?

Savage was also correct when he said that if prenatal infanticide is illegal, “abortions will still occur.” Yet this is much like the reasoning, which we’ve heard from permissive, libertine parents, that they’ll allow their young teenagers to have sex under their roof because “they’ll do it anyway.” So you might as well have it structured and “safe.” Or it’s like the thinking behind that government program providing free hypodermic needles to heroin junkies: We can’t stop them from doing drugs, so let’s at least remove the danger.

If a prerequisite for a law or rule was that it could eliminate all the targeted evil, there could be no laws or rules at all. But the only justification it needs is that it is just and would do more good than harm. When assessing this, bear in mind ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle’s observation that the purpose of law is to make men good.

While this may offend libertarian ears, law does have this effect. How often do we hear people proclaim as an argument, “But it’s the law!” This illustrates the impact law has on thinking: Just or not, it sends a strong message that the prohibited action is bad, something good people don’t do.

But would criminalizing prenatal infanticide do more good than harm? Well, to use a twist on a line from French economist Frederic Bastiat, a bad social analyst observes only what can be seen. A good social analyst observes what can be seen — and what must be foreseen.

Being mindful that the unborn baby is just that — a baby, every bit as human as his mother — illuminates matters. It was very easy to see the victims of botched back-alley prenatal infanticide. Yet not as visible is the fatality in 100 percent of prenatal infanticide cases, illegal or legal: the child. Moreover, not at all seen 60 years ago was how many people would be killed if all legal constraints against prenatal infanticide were removed.

Of course, now we know: 60 million since the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision.

Were there really 10 million prenatal infanticide-related deaths per decade in the early 1900s?

Lastly, Savage pointed out that prenatal infanticide has always existed and was practiced in every primitive society he’d ever studied (he’s a scientist). Yet this is just another way of saying sin has always existed. Those primitive societies also once generally engaged in human sacrifice and cannibalism as well. Western civilization ended that barbarity.

This could make one wonder: Who will show us the way out of our barbarity?