Southern military leaders were well-schooled in the guerrilla tactics refined by Spanish patriots in the Peninsular War against Napoleon — referred to in history texts as the Corsican despot’s “Spanish ulcer.” With Lee’s blessing, Southern commanders could have melted into the countryside and waged an insurgency lasting for years, or decades, bleeding the victorious Union government until it permitted the South — in some form — to go free.

The prospect of partisan resistance by the South haunted many Union Army commanders, particularly William Tecumseh Sherman, whose murderous “march to the sea” had done more than its share to whet the Southern appetite for vengeance. Soldiers and statesmen on both sides of the War Between the States were similarly plagued by images of Missouri, a border state where partisan warfare degenerated into unalloyed barbarism.

Missouri was “the war of 10,000 nasty little incidents,” recalls historian Jay Winik, a “killing field” that “produced the most bloodthirsty guerrillas of the war” — including William Quantrill, “Bloody” Bill Anderson, and Frank and Jesse James. The Quantrill-led raid on Lawrence, Kansas, in 1863 resulted in the slaughter of hundreds: “Black and white, ministers, farmers, merchants, schoolboys, recruits,” writes historian T.J. Stiles. That atrocity prompted General Thomas Ewing, Jr., military governor of western Missouri, to issue General Order 11 on August 25, 1863. That directive expelled everyone residing within the area.

“There [are] hundreds of people leaving their homes from the country and God knows what is to become of them,” wrote Colonel Bazel F. Lazear of the pro-Union Missouri State Militia. “It is heart sickening to see what I have seen since I have been back here. A desolate country and women and children, some of them almost naked. Some on foot and some in old wagons. Oh, God, what a sight to see in this once happy and peaceable country.”

But this expulsion did nothing to put an end to the parade of horrors; instead, it added fuel to the insurgency — and Federal forces responded in kind.

“The Union soldiers hunted the guerrillas like animals, and in return, they, too, eventually degenerated into little more than savage beasts, driven by a viciousness unimaginable just two years earlier,” records Winik. “By 1864, the guerrilla war had reached new peaks of savagery. Robbing stagecoaches, harassing citizens, cutting telegraph wires were everyday occurrences; but now it was no longer simply enough to ambush and gun down the enemy. They had to be mutilated and, just as often, scalped. When that was no longer enough, the dead were stripped and castrated. In time, even that was insufficient. So ears were cut off, faces were hacked, bodies were grossly mangled.”

Quantrill’s raiders rode with scalps dangling from their bridles, and brandished other grisly trophies — ears, noses, teeth, and fingers removed from their victims. Union reprisals were just as vicious. “Groups of revenge-minded Federals, militia and even soldiers, became guerrillas themselves, angrily stalking Missouri, tormenting, torturing, and slaying Southern sympathizers,” writes Winik. “Reprisals and random terror became the norm, and the entire state was dragged into an incomprehensible and accelerating whirlpool of vengeance.”

“There’s something in the hearts of good and typical Christians … which had exploded,” reported one stunned Union commander. “Pandemonium itself seems to have broken loose,” commented the Kansas City Journal of Commerce in 1864, “and robbery, murder and rapine, and death run riot over the country.”

Missouri had become an evil proverb by April 1865, when Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia — bloodied, emaciated, but still valiant — was checkmated. But the devastated South still boasted several armies capable of mounting serious partisan campaigns. Men like Mosby and Forrest had the capacity to create many Missouris throughout the Southland.

Lee wouldn’t permit it. And his moral authority alone was what prevented it.

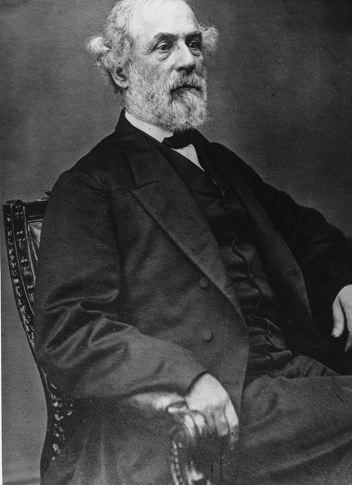

General Lee exemplified Christian patriotism. Though he may not have made Augustine or Aquinas his bedside reading, he understood the Just War doctrine of proportionality. It was his judgment that the evils to ensue from continuing the war as a guerrilla campaign would be greater than those resulting from surrender. So the general, clothed in the serene dignity that never deserted him, made the grim and bitter visit to the courthouse in the village of Appomattox, Virginia. Lee’s surrender was an act of patriotic love for his “country,” Virginia. It also reflected his wistful hope that the federal government would reconstruct the Union in a just and magnanimous fashion.

Years later, as the victorious Radical Republicans in Congress imposed their will on the prostrate South, Lee came to question his decision. Shortly before his death in 1870, Lee confided to former Texas Governor Fletcher Stockdale. “Governor, if I had foreseen the use those people designed to make of their victory, there would have been no surrender at Appomattox Courthouse; no sir, not by me,” declared General Lee. “Had I foreseen these results of subjugation, I would have preferred to die at Appomattox with my brave men, my sword in my right hand.”

Social Engineers With Bayonets

Reconstruction was not simply an exercise in knitting together anew the sundered Union. It was an effort to eradicate the culture of the South and create an entirely new one through military dictatorship. Although the abolition of chattel slavery was an unqualified blessing, one that was badly overdue, it was only a small part of the penalty the South was forced to pay. And it was a process that had already begun in the late stages of the war as the desperate South offered freedom to those black men who would bear arms on behalf of the Confederacy.

As an experiment in social engineering, Reconstruction was immensely profitable for many corrupt, well-connected people. It was also a monumental disaster for race relations, since it exploited the emancipated blacks as a political resource, while pitting them against white Southerners. And it provoked, to a limited but still tragic extent, the same variety of terrorism that had turned Missouri into an American killing field.

“After the Civil War,” writes Johns Hopkins historian Benjamin Ginsberg in his book The Fatal Embrace, “radical Republicans sought to drastically alter the social and political structures of the states of the former Confederacy. They sought to establish a regime that would break the political power of the planter class that had ruled the region prior to the war.”

The leading lights on the congressional Joint Committee for Reconstruction were Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts and Rep. Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania. Both were Radical Republicans who insisted that the Southern states be treated as conquered provinces.

Prior to the war, the right of states to secede from the Union had been explicitly recognized in several state constitutions, and taught as a valid constitutional principle at West Point. However, Sumner insisted that the exercise of that recognized right amounted to “a practical abdication by the state of all rights under the Constitution,” and insisted that the post-war Southern states were now under “the exclusive jurisdiction of Congress as [any other conquered] territory.” Rep. Stevens was even more vindictive. As historian Paul Leland Haworth astringently wrote in his 1912 study Reconstruction and Union, Stevens “possessed much of the sternness of the old Puritans, without their morality.”

Leftist historian Daniel Lazare, an admirer of Stevens, notes that he was “the most powerful figure” in the Reconstruction-era Republican Congress, which was “a surprisingly disciplined and militant body.” Stevens “saw the war in terms that were as much social as military; his tone was apocalyptic and revolutionary,” continues Lazare. He “was openly contemptuous of constitutional constraints — he once called the Constitution ‘a worthless bit of old parchment.’” Stevens insisted on dealing with the “late Confederate states as conquered provinces possessing no rights the conquerors were bound to respect.”

Stevens was a key architect of the Reconstruction Act of March 1867, which, according to Lazare, was inspired by Oliver Cromwell’s military dictatorship in England:

Where Cromwell had divided England up into eleven military districts, each governed by a major general with wide-ranging powers, the newly radicalized Congress divided the South into five districts, each ruled by a military governor under the overall direction of General Grant. The military authorities banned veterans’ organizations and other groups deemed threatening to the new order, fired thousands of local officials and half a dozen governors, and purged state legislatures of pro-Confederate elements as well. A twenty-thousand-strong army of occupation, aided by a black militia, enforced order…. Political rights were withdrawn from thousands of Confederates who had been granted executive clemency by the President, and all told some one hundred thousand white voters were stricken from the rolls.

As a condition for readmission into the Union (and the end of military occupation), each state was required to convene a constitutional convention for the purpose of repudiating its act of secession, and ratifying the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. (How the Constitution could be legitimately amended by occupied provinces not considered part of the United States has never been adequately explained.)

Military governors in the Southern states “proceeded to create a new electorate and through it new civil governments,” records Dr. Haworth. In most Southern states, the new electorate was drawn heavily from among previously disenfranchised whites and newly emancipated blacks, who had little or no understanding of representative government — and were thus easily manipulated by “carpetbaggers,” corrupt and ambitious Northerners who had arrived in the South to enrich themselves. As a consequence, writes Haworth, “the constitutional conventions chosen by this electorate included in varying degrees men utterly unfitted by previous training for the work of constitution making” — but eminently suited to the work of plundering what remained of the conquered South.

Reconstruction and Plunder

A coalition of Radical Republicans, carpetbaggers, and “scalawags” (opportunistic Southerners) soon became entrenched in power. Haworth describes it as a “sinister alliance” sustained not only by Congress and federal troops but also by a secret society called the “Union League” or “Loyalty League,” “under cover of which, with awe-inspiring rites, the new voters received political instruction from the white [Reconstruction] leaders…. In some cases, its members resorted to whipping or otherwise maltreating Negroes who became Democrats.” In many Southern communities, Reconstruction amounted to official corruption, supported by military occupation and enforced through covert terrorism.

A hint of things to come came after the seizure of the cotton crop immediately after the war. “I am sure I sent some honest agents South,” commented U.S. Treasury Secretary Hugh McCulloch, “but it sometimes seems very doubtful whether any of them remained honest very long.” “From the estimated $100 million worth of captured property sold, the government received only $30 million,” notes Jeffrey Rogers Hummel in his book Emancipating Slaves, Enslaving Free Men. The seeds of corruption blossomed handsomely as Reconstruction took root.

“Many of the state governments developed spending programs designed to bolster their political support by giving a variety of groups a stake in their preservation,” recalls Ginsberg. “These programs included a substantial expansion of state patronage positions, economic development, particularly railroad construction, and elaborate public works projects.” Not surprisingly, “many of the radical governments had to turn to deficit spending and borrowing to finance their ambitious development and public works programs.”

The results were just what could be expected. In South Carolina, the Reconstruction government eviscerated the economy through profligate spending and outright plunder. Between 1868 and 1874, the state government rolled up over $14,000,000 in public debt (at a time when that amount was a formidable figure). During the same period, the aggregate value of private property slumped from $490,000,000 to $141,000,000, in large measure because of confiscation and other undisguised larceny conducted or tolerated by the military government.

Franklin Moses, a South Carolina “scalawag,” was a typically rapacious Reconstruction oligarch. As speaker of the Reconstruction-era state House of Representatives and then as governor, Moses “proved to be especially adept at raising money through the sale of state securities,” Ginsberg observes. While running up huge debts and undermining what remained of the state’s economy, Moses — who became known as the “Robber Governor” — “organized a 14,000-man state militia composed mainly of black troops and led by white officers.” This praetorian guard was used to intimidate potential Democratic voters during the 1870 election. It was also used to stymie attempts to execute legal judgments against him.

Similar scenes played out elsewhere in the conquered South. In 1866 and 1867, Louisiana under the Reconstruction dictatorship was a spectacle of “wholesale corruption, intimidation of new voters by thousands and tens of thousands, political assassinations, riots, revolutions — all of these were the order of the day,” writes Haworth.

Caught in the Lethal Pincers

The crimes of the “sinister alliance” did not go unanswered. “The new order of things was backed up by northern bayonets, open resistance was hopeless,” Haworth points out. Thus ensued a revival of the option that had been dismissed at Appomattox: guerrilla warfare by way of secret societies, most notoriously the Ku Klux Klan, as well as the White Camelia, the Pale Faces, and the White Brotherhood.

Those who enrolled in the Reconstruction-supported secret society, the Union League, purported to be acting out of a noble desire to vindicate the rights of formerly enslaved black people. The Klan and its allies used as “justification” for their terrorist acts the legitimate need to protect the South from the depredations of corrupt Reconstruction officials, and widespread lawlessness that was allowed to fester in many communities under federal military rule. But in time-honored fashion, these factions were firmly under the control of immoral, ambitious men, lusting for power. With helpless, innocent populations caught in the middle, the federal government exploited the crisis to expand its dictatorial power yet again.

In 1870 and 1871, Congress passed two Enforcement Acts, the second of which was popularly known as the “Ku Klux Act.” That measure was used in October 1871 by General Grant (who had been elected president in 1868) to designate nine South Carolina counties “in rebellion.” Troops were dispatched by Grant to arrest hundreds of people, which had the understandable effect of exacerbating an already terrible situation.

From our contemporary perspective, Reconstruction of the American South appears uncannily to prefigure more recent forays into nation-building — particularly the ongoing misadventure in Iraq:

• The policy was garbed in the rhetorical robes of noble intentions;

• It was driven by ideologically zealous politicians determined to remold a recalcitrant population through force;

• It was carried out by politically connected opportunists who seemed determined to steal everything they could lay their hands on;

• It provoked violent guerrilla resistance from some segments of the occupied population.

• And the policy required the U.S. Army to carry out tasks entirely incompatible with its constitutional purposes.

Reconstruction, according to Professor James J. Schneider of the Army Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, “represented, from a military standpoint, the darkest days in the history of the Army.” It was “an effort in peacekeeping, peace enforcement, humanitarian relief, nation-building and, with the rise of the Ku Klux Klan, counterterrorism,” wrote Schneider in the April 1995 issue of Special Warfare. “The Reconstruction activities of Army units were unprecedented in their time, and they sound remarkably familiar today.”

For roughly a decade, Reconstruction continued to sow misery in the South and cultivate federal corruption. Its end came — appropriately enough — as a result of a backroom political deal growing out of the 1876 presidential election.

Dirty Dealings

When Ohio’s Republican Governor Rutherford B. Hayes went to bed after the first returns came in, he was convinced that he had lost to New York Governor Samuel J. Tilden, the Democratic standard-bearer. Hayes had lost the popular vote by a margin of roughly 164,000 votes. However, the Republicans contested the electoral votes of South Carolina, Louisiana, and Florida; if Hayes could win all three states, he would have the 185 electoral votes needed for victory.

In January 1877, Congress created an election commission composed of eight Republicans and seven Democrats. Given that alignment, it’s not surprising that each of the contested state returns were all awarded to Hayes by an 8-7 vote.

Since this outcome was unbearably pungent even to those inured to the casual corruption of the period, the Republican leadership offered the Democrats multiple consolation prizes in exchange for the presidency: a cabinet post, patronage jobs, subsidies for “internal improvements,” and, most enticingly, an end to Reconstruction.

“In Louisiana and South Carolina, dual governments existed, and peace between the factions had been preserved only by the presence of federal troops,” writes Haworth. “In the last days of the electoral count, certain Republican leaders had secretly promised that if filibustering would cease, Hayes, upon becoming president, would withdraw the troops and allow the Carpetbagging governments to totter and fall…. In less than two months after the inauguration, the Carpetbag governments vanished into thin air.”

But their stench remained. For more than a year, Congress grappled with proposals to enact a statute explicitly banning use of the Army as a domestic law enforcement agency — a policy upon which the entire corrupt enterprise of Reconstruction had depended. Finally, on June 18, 1878, an appropriations bill was amended with an austere, one-paragraph rider forbidding the use of the Army as “a posse comitatus, or otherwise, for the purpose of executing the laws” without specific authorization from Congress.

The so-called Posse Comitatus Act is brief and too easily circumvented. But it is a valuable expression of an indispensable constitutional principle: the separation of military and law enforcement powers. And it is also a useful reminder of the horrors that can be, and have been, visited on Americans when that separation breaks down.

Photo: AP Images