"The free market for all intents and purposes is dead in America," said Sen. Jim Bunning (R-Ky.). "The action proposed today by the Treasury Department will take away the free market and institute socialism in America." Senator Bunning’s comments, made in the wake of the bank bailout, and followed by the election of a president who has openly advocated redistribution of wealth, should make Americans pause, for the formerly unthinkable is upon us.

Socialism, the Utopian economic and political system that promises equality, prosperity, and universal peace through the workings of a collectivist state, has repeatedly been exposed as a colossal failure. Its history, marked by failed societies and brutal dictatorships, is quite literally littered with the bodies of millions of innocents, and yet in the United States we stand on the brink of a socialist abyss, the edge of which looms ever closer as time passes. The conflict between individual and collective rights rages on, but despite socialism’s historical failures, it remains attractive to those vulnerable to its false promises of egalitarianism and economic equality. Instead of being relegated to its own proverbial "dustbin of history," it continues to entice well after its failures and crimes have been laid bare for all to see.

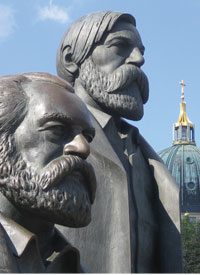

Socialism/Communism

Socialism and its twin partner communism cannot be separated, and in fact socialism has its modern roots in the Communist Manifesto. It was there that Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels laid the blueprint for a type of socialism that called for total social change and class warfare. "Let the ruling classes tremble at a communist revolution. The proletarians [laborers] have nothing to lose but their chains. They have the world to win," wrote the two socialist revolutionaries in 1848. They promised the world to laborers; they would take the property from capitalists (whom they call bourgeoisie) for the benefit of laborers: "The distinguishing feature of communism is not the abolition of property generally, but the abolition of bourgeois property…. In this sense, the theory of the Communists may be summed up in the single sentence: Abolition of private property."

They claimed that laborers were held down by capitalists, that only capitalists benefited from capitalism, and that communism would literally stop the buying and selling of goods and allot everyone an equal amount: "In communist society, accumulated labor is but a means to widen, to enrich, to promote the existence of the laborer…. Communism deprives no man of the power to appropriate the products of society; all that it does is to deprive him of the power to subjugate the labor of others by means of such appropriations." In truth, the working classes had much to lose under socialism, and for later generations the shackles of communism would weigh heavy; for in practice, a central person or group had to control the redistribution of the wealth, and under communism power was concentrated for the benefit of the few at the controls — at the expense of the masses, no matter the harm and the suffering visited upon the masses.

In a later preface to the 1888 edition of the Manifesto, Engels made it clear that various socialist Utopian systems of the mid-19th century and earlier were dead and had been replaced by a "crude, rough hewn, purely instinctive sort of communism." This was the model that would usher in the Russian Revolution and set the stage for a class of 20th-century societies that featured two distinctive qualities: political dominance by a revolutionary party, and nationalization of the means of production coupled with the transfer of personal property to the state. Although it cannot be said that all socialist countries are communist, it is safe to say that all communist countries are socialist, and in the case of Venezuela, we see a socialist state moving along a trajectory that will ultimately end in a classic communist state.

At the very least, all of the socialist societies that came into being after the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution necessarily reflect some basic characteristics of the Soviet model — central control and coercion. In Russia the cruelties endured under the Tsar, which were to be replaced by equality and welfare, were merely replaced by a more brutal hierarchy and an economic system that crushed individual enterprise and guaranteed a dysfunctional economy. Worse, those groups that had fared well during the monarchy ultimately lost everything. Lenin’s classless system required the collectivization of farms, and the Kulaks, those independent farmers who had managed to retain control of their property, were ruthlessly targeted between 1930 and 1932 for extermination. Resisters were shot or deported to Siberia or the northern forests where they endured forced labor.

The great Ukrainian famine of 1932-33 was the result of the Soviet state confiscating food and literally starving the rural population into submission. In the end six million died. The false promise of a utopian classless society free from oppression meant death and misery for millions of Russian Ukrainians, as it did for millions of others who died at the hands of 20th-century communist regimes.

From the very beginning of the socialist experiment in 1917, millions have been ushered to their deaths by brutal communist regimes intent on consolidating power. Those who doubt early communist motives need only consider Lenin’s actions. His bid to "build socialism" was the motivation behind the reign of terror that historian Stéphane Courtois, the editor of The Black Book of Communism, characterized as the "utopian will to apply to society a doctrine totally out of step with reality." It is the essential fallacy of socialism, its inability to deliver the goods, its inherent imperfection, that inevitably moves its architects along a path of increasing state control, and in the case of communism results in extreme brutality. In 1920, Leon Trotsky, who rose to a level of power in the new Soviet state just below that of Vladimir Lenin, claimed, "Dictatorship is necessary because this is a case not of partial changes, but of the very existence of the bourgeoisie. No agreement is possible on this basis. Only force can be the deciding factor…. Whoever aims at the end cannot reject the means." As the original architect of the first socialist state, Lenin, and his successors, never shrank from employing brutality to ensure the survival of their socialist Utopia.

The totalitarian dimension of communist socialism has its roots in the belief that all aspects of society had to be transformed. Class warfare and the extermination of "enemies of the state" were constant characteristics of the Soviet state’s progeny – China, North Korea, Cuba, etc. It was not sufficient to merely defeat the enemy. Whether it was the Kulaks, peasants unable to pay their taxes, or the intelligentsia, extermination awaited them all. In his Defense of Terrorism, Trotsky wrote of the need to eliminate the tenacious bourgeoisie, "We are forced to tear off this class and chop it away. The Red Terror is a weapon used against a class that, despite being doomed to destruction, does not wish to perish." Trotsky’s socialist doctrine of terror was so ingrained in the minds of party members that it provided justification for the enormous crimes perpetrated during Stalin’s regime. One former party member, a gulag detainee herself, wrote, "The truth is that all of us, including the leaders directly under Stalin, saw these crimes as the opposite of what they were. We believed that they were important contributions to the victory of socialism."

In 1971, the U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Internal Security released a study entitled The Human Cost of Communism in China. The report estimated the deaths attributed to the communists in China, at that time, to be between 34 and 64 million people. In the Soviet Union, deaths were estimated between 35 and 45 million.

And so it was with subsequent socialist revolutions, whether it was the execution and deportation of the Cuban "bourgeoisie" by Castro, or the extermination or re-education of the Cambodian urban population from 1975 to 1978, or the ongoing incremental destruction of the North Korean population by Kim Jong-Il. Socialism remains a system predisposed to a profound brutality, and one that inevitably fails to deliver a promised peaceful paradise.

Willing to Be Duped

Americans and Europeans are unlikely to face a communist reign of terror on the road to socialism, meaning that they are vulnerable to socialism’s siren call, and its tempting promises — whether the promises are meaningful or not. And once accepted it becomes very difficult to raise a voice against the monster and its crimes. Quoted in The Black Book of Communism, Bulgarian philosopher Tzvetan Todorov lays out the paradox that faces those that voluntarily accept the inevitable servitude that comes with socialism:

A citizen of a Western democracy fondly imagines that totalitarianism lies utterly beyond the pale of normal human aspirations. And yet, totalitarianism could never have survived so long had it not been able to draw so many people into its fold. There is something else — it is a formidably efficient machine. Communist ideology offers an idealized model for society and exhorts us toward it. The desire to change the world in the name of an ideal, is after all, an essential characteristic of human identity…. Furthermore, Communist society strips the individual of his responsibilities. It is always "somebody else" who makes the decisions. Remember, individual responsibility can feel like a crushing burden…. The attraction of a totalitarian system, which has had a powerful allure for many, has its roots in a fear of freedom and responsibility.

The "fear of freedom and responsibility," of which Todorov writes, explains the establishment of redistributive bureaucracies on the European continent and the increasing shift toward socialism, both corporate and individual, in the United States. The presidential election of a candidate who has made known his redistributive tendencies points the needle significantly closer to a full-blown socialist state in which individual responsibility is obliterated and replaced with the loss of liberty and personal property.

Redistribution as opposed to a market system is the raison d’etre of the socialist system. In the perfect socialist system everyone works, and the wealth produced is ultimately redistributed as welfare, based upon Karl Marx’s famous dictum, "From each according to his abilities, to each according to his needs." A true socialist system relies upon a planned economy in which the centralized government controls the productive resources. In the end, at least in theory, no one gets rich, but no one wants for anything. In reality, however, it works quite differently. Socialist bureaucracies with heavily planned economies lead to shortages and inequality. In planned economies it is impossible to purchase materials on an open market, so their availability depends upon the plan and central distribution. Such likely drawbacks were pointed out even before 1848, causing Marx and Engels to try to defend the philosophy of communism against its critics:

It has been objected that upon the abolition of private property, all work will cease, and universal laziness will overtake us.

According to this, bourgeois society ought long ago to have gone to the dogs through sheer idleness; for those who acquire anything, do not work. The whole of this objection is but another expression of the tautology: There can no longer be any wage labor when there is no longer any capital.

All objections urged against the communistic mode of producing and appropriating material products, have, in the same way, been urged against the communistic mode of producing and appropriating intellectual products.

But the accusations proved accurate — Marx and Engels wrong. In Stalin’s 1930s Soviet state, Russians lived with the consequences of a planned economy on a daily basis. Food scarcity was a constant threat to survival. Stalin’s collectivization of the farms and his emphasis on building heavy industry nearly killed Soviet agriculture. The survivors of collectivization fled to the urban centers and emptied the food shelves. The Soviet state responded by establishing a network of closed distribution shops (open to particular groups only), and implementing a hated rationing system. Black-market activity grew and remained a fixture of Russian culture for 50 years.

Collectivism is unsustainable. It is a mirage that promises liberation and equality to the worker, but in the end delivers neither. Without the profit motive — the right to keep the fruits of your labor and ingenuity — the economy stagnates and dies.

Party leaders understood this, but they kept up the charade and allowed a second economy to develop and even legalized it in some cases. Food production on small plots, off-hours construction, typing, all of these and more were at times tolerated and at other times prohibited. Sometimes it took the form of an official government act that introduced limited market mechanisms and incentives. After 1968, Hungary experienced a tremendous growth in its "second economy," and likewise in Cuba after Castro’s 1986 "Rectification." Economic reforms that introduced elements of a market economy ultimately spelled the end of the classic socialist Soviet-bloc hegemony. Even a die-hard socialist knows when the economic game is up. In the end a voluntary exchange of goods and services guided by a market-oriented economy with protection of personal property is always more successful than allocation determined by politicians and party members.

Socialism does not work even when the intent of those in control is to make it work. But it must not be overlooked that socialism is ultimately about controlling the wealth, as opposed to sharing the wealth. A government that is powerful enough to give the people everything they want — "free" education, healthcare, housing, etc. — by taking from some in order to give to others, is also powerful enough to take everything the people have for the benefit of the few in control. Dictators from Lenin to Hitler surely understood this, and for them the false promises of socialism were simply bait intended to capture the support of the uninformed and misinformed masses.

Enacting Cultural Reform

But while the lure of redistribution and its promised benefits is critical to the socialist strategy, it cannot completely explain its allure. Social engineering plays as important a role. The idealism that Todorov speaks of finds its home in socialism, for what better way to implement sweeping social changes than through the totalitarian nature of socialism and the surrender of liberty that goes with it. A constant characteristic of all socialist societies is the implementation of projects designed to intervene in all facets of life in order to gain control in the name of brotherhood.

The promise of equality often fails to extend to established religions, which often face constraints that impinge upon their ability to deliver traditional messages. Religion is usually attacked, and if tolerated is replaced with a "socialized" version in which the state message is paramount. Religious rituals are replaced with state rituals designed to inculcate socialist ideals, or to increase a secularist outlook.

During the summer of 2008, Fr. Alphonse de Valk, a Catholic priest living in Canada, was brought up on allegations of violating Section 13 of Canada’s Human Rights Act — the now-infamous "hate act" clause that dogged columnist Mark Steyn for his alleged crime of exposing Muslims to "hatred and contempt." Macleans had earlier featured an excerpt of Steyn’s book American Alone, in which he posits that the West’s plummeting birth rate will result in an increasingly Muslim Europe, given the latter’s higher rate of birth and immigration. He was subsequently hauled before a British Columbia Human Rights Tribunal. Steyn and Macleans were eventually cleared of wrongdoing, but the whole affair points to what can happen when socialist tendencies creep into a democracy. Likewise, for simply defending the Church’s teaching on same-sex "marriage," Fr. de Valk faced similar charges and a trip to the tribunal, which bears a striking resemblance to Stalinist-era kangaroo courts, only without the dreaded efficiency.

Free speech is always the first thing to go in a socialist society bent upon implementing its ideals. Soviet Russia maintained complete control of the press with various state organs, including Pravda and Izvestia. These state-controlled publications were mandatory reading for party members, and transmitted the party line and ensured compliance from the 1920s until the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. From there it is but a short journey to total oppression.

The much-talked-about ideal of brotherhood in the socialist context can never be implemented because compulsion kills the very notion of brotherhood. It cannot be achieved by social engineering, by the suppression of truth and the destruction of free speech. Rather it is the path to tyranny.

Socialism Tried and Found Wanting

Today’s promise of "soft" socialism, although free from the shackles of a planned economy and the brutal tyranny of Soviet-era Russia, nevertheless imitates some of the flaws of classic socialism, and promises as much. The belief that the government can solve basic economic and societal problems has given rise to programs like socialized medicine, Social Security, reparations, and welfare — all promising to free us from the vicissitudes of life in exchange for our freedom. But they are doomed to failure because like all socialist programs, they ignore the fundamental principles of human behavior, including certain natural inequalities.

One needs to look no further than President Lyndon Johnson’s attempt to create the Great Society through a series of socialist reforms during the 1960s for an example of the failed promises of socialism in the United States. Johnson shared much with perhaps the greatest U.S. progressive social reformer, Franklin D. Roosevelt, for each saw the government as the tool to build a vast commonwealth based on their own economic and redistributive objectives.

Johnson ushered in an array of socialist programs designed to reduce poverty, increase access to medical services, and improve education, among other things. Federal aid was augmented by an aggressive system of grant-in-aid to states in order to meet goals. Grant-in-aid outlays nearly doubled between 1964 and 1968. In fact, more grant programs (210) were launched during Johnson’s administration than all of the years dating back to the first grant enactment in 1879. As the numbers increased so did the range of programs. New programs like Medicaid, and urban renewal programs like Model Cities, expanded the liberal socialist agenda beyond the boundaries of the traditional agenda. In the end some programs like Model Cities were unmitigated failures, and the cost of the programs and their questionable levels of success overwhelmed Americans.

According to Charles Murray, author of Losing Ground, Johnson’s Great Society was an unmitigated failure. Murray posits that if trends that had begun during the Eisenhower years were allowed to continue, America would have witnessed significant progress in reducing poverty. But because of Johnson’s programs, they were not allowed to continue; hence, the numbers of those living in poverty, despite the availability of federal and state assistance, remained relatively unchanged. Murray writes that by 1980, the poor were substantially worse off than before the beginning of the Great Society experiment:

The unadorned statistic gives pause. In 1968, when Lyndon Johnson left office, 13 percent of Americans were poor, using the official definition. Over the next twelve years, our expenditures on social welfare quadrupled. And, in 1980, the percentage of poor Americans was — 13 percent.

Why did Johnson’s socialist experiment fail despite an increase in social welfare costs that increased by 20 times from 1950 to 1980? Like all aspects of socialism, Johnson’s anti-poverty programs removed personal responsibility and status rewards from the equation. Status is a reward that society bestows upon its citizens for leading satisfactory lives. In the United States, status is not immutable. Even those at the bottom of society’s ladder can envision a day in which they move up. Put simply, Johnson’s expansion of the welfare state discouraged behaviors that formerly engendered an escape from poverty. Incentive was removed and, worse yet, status was withdrawn from working-class families at the lower end, who were told that the system was to blame for their inability to move up the ladder of success. So the promise of an escape from poverty or lower class status became yet another failed promise of the socialist dream. The incentive to achieve and compete was destroyed and, despite the billions of dollars thrown at it, poverty remained a constant fact.

All the socialist economies are failures at some level:

• Mengitsu’s communist regime in Ethiopia was defeated in 1991 after the Soviet Union failed to provide aid during an anti-communist insurrection. His rule was typically communist/socialist — state-imposed famine, deportations, brutality, etc.

• France has constant labor upheaval, absurd cradle-to-grave benefits, and the looming inability to pay for it all except through increased immigration from North African countries that are culturally hostile to France.

• Germany’s healthcare interventions have led it to try to save money by limiting the salaries of doctors. Doctors are fleeing the country en masse, leaving Germany with a serious shortage.

Socialism saps incentive, destroys freedom, and leads to tyranny. Yet it continues to promise a Utopia to many despite the fact that every socialist experiment has ended badly from an economic and moral standpoint. It promises everything from the abolition of poverty to the destruction of bigotry and inequality. But it has never delivered.