Americans plopped by others on the imaginary “Far Right,” such as Senator Robert Taft, President Calvin Coolidge, and Congressman Ron Paul believe(d) in individualism and in Christianity, which are the antitheses of totalitarianism and secular collectivism. During the brief period of the Nazi-Soviet Nonaggression Pact, from August 1939 to June 1941, the absurdity of placing one of these evil regimes on the “Far Right” and the other on the “Far Left” was grotesquely clear.

During these 22 months, the term “Communazi” was used to describe those who fell in line with the nonaggression pact to attack America. Members of the Communist Party USA and fellow travelers joined the Bund (the pro-Nazi organization in America with close links to Berlin) and Bundists joined the Communist Party in America.

What happened in America happened in Europe as well. Moscow had already ordered German Communists to join the Nazi Party and the common themes of both movements — hatred of Christians and Jews (Stalin had just about purged all Jews from the Politburo and important positions of the Soviet government, just as Himmler had ordered that every member of the SS had to renounce Christianity) and contempt for liberty in all its forms made this an easy step.

Few in these evil movements found any moral qualms about supporting regimes that had heretofore been attacked as ghastly. This sort of complete flipping overnight was something that George Orwell noted and included in his dystopian masterpiece, 1984, in which the three global empires — Oceania, Eastasia, and Eurasia — would be in ever-changing alliances of two against one, and the propaganda of each empire was such that the new alliances were presented as having been always true.

Although the term “Communazi” was wonderfully descriptive of the godless and monstrous regimes in Moscow and Berlin, the term was banished from public discourse after June 1941, when Hitler invaded Russia and FDR decided that “Uncle Joe” Stalin was a good guy. But the reality of the “Communazi” could not be so easily purged from history. There were such men throughout Europe.

France, in many ways, was a perfect example of this noxious stew of men opposed to ordered liberty and American values. Jacques Doriot joined the Socialist Youth in 1916. In 1920 Doriot joined the French Communist Party. He rose rapidly through the ranks to become a member of the Presidium of the Executive Committee of the Communist Internationale in 1922. By 1923, Doriot was Secretary of the French Federation of Young Communists. He was imprisoned for his revolutionary Marxist politics.

Jacques Doriot was not just a Communist, but he also was one of the leading Communists in the world. In 1925, Ho Chi Minh became one of his protégés. Brian Crozier, in his book The Man Who Lost China, writes that American Earl Browder, the Frenchman Jacques Doriot, and the Briton Tom Mann had been sent by the Comintern to China, where each made political speeches in 1927. Jacques Doriot, Mayor of St. Denis, in 1930 is listed as one of the leaders of the French Communist Party. In 1934, Doriot was actually the Floor Leader of the French Communist Party in the Chamber of Deputies.

But the name Jacques Doriot is absent in the late 1930s. Why? Doriot in 1934 advocated joining other parties of the Left and he was expelled from the French Communist Party in 1934. In spite of his expulsion, Doriot continued to call himself a “Communist” for the next two years. In 1936, he became leader of the French Popular Party, and whole-heartedly collaborated with the Nazis. Yet as late as 1938, Gunther wrote of him: “Doriot, who wants his revolution right away, says that Stalin, a Russian ‘imperialist,’ has sacrificed the true needs of France to those of Russia and has betrayed the ‘true’ communists.”

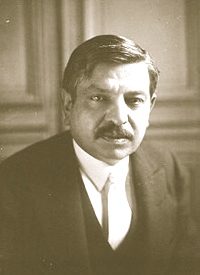

An even more interestingly example is Pierre Laval (pictured above), who became President of the Council of Ministers of Vichy France (the part of unoccupied France after the surrender of France in 1940, which collaborated with Hitler) 70 years ago, on April 18, 1942. Laval was an active, almost an enthusiastic, collaborator with Nazi Germany. So, if one is bewitched by the false ideological spectrum with Nazis at one extreme and Soviets at the other, Laval’s career should have been on the so-called “Far Right,” but that was not the case at all.

Laval was emphatically on the “Far Left” for most of his life. When he ran for office in 1914, he was an “extreme left-winger” according to his biographer and he was a Communist when France entered the First World War. John Gunther, in his 1938 book, Inside Europe Today, wrote of him: “He began his political life as a violent socialist, and until at least 1922 he was known as a man of the extreme Left.” He went on to say that when the Left coalition collapsed and Poincare formed a regime, “Laval was very much out in the cold. He was far too Leftish — still.”

Then Laval, according to establishment political thinking, began to move to the mythical “Far Right.” Did this really mean anything? The Marxist Schuman wrote of Laval in 1939: “Wits noted that his name read the same from left to right as from right to left” — laval is a palindrome like bob or anna — suggesting that Laval had no true ideology. He was a traitor to France but also a traitor to any principles beyond power. Pierre Laval was the penultimate Communazi.

The move to the “Right” began soon after the Nazis came to power. In 1934, Laval, as the French Foreign Minister, reached the understanding with Fascism that allowed the French and Fascists to combine to stop the Nazis in Austria. Why did he work with Mussolini? Pierre van Pasasen in 1939 wrote that Laval may have felt under personal obligations to Mussolini because the two had both been Communists before the First World War, and that this ideological connection helped the French political leader and the Fascist leader of Italy to form a common alliance.

But after that, Laval as Foreign Minister negotiated a mutual assistance pact with the Soviet Union to oppose Hitler. How does that fit in with his image as on the “Far Right”? It doesn’t, of course, and then after the Germans conquered France in 1940, Laval became a leader of the collaborationist Vichy Government, which continued after Hitler launched Operation Barbarossa in June 1941, which ended the alliance between Soviet Russia and Nazi Germany.

Laval, the young Communist, was now Laval, the French operative who helped work to defeat the Soviet Union. So how did his career and life end? Laval was executed for collaborating with the Nazis — the perfect example of the silliness of ideological labels: the perfect example of the “Communazi.”