It wasn’t just Oval Office tape recordings that Richard Nixon wanted to get rid of. According to documents made public last week, the 37th president ordered the removal of pieces of modern art placed in embassies during the Kennedy administration. Calling such pieces “little uglies,” on January 26, 1970 Nixon issued a memo calling the examples of modern art and architecture in government offices “incredibly atrocious.”

Last Monday, the National Archives via the Nixon Library located in Yorba Linda, California, released some 280,000 pages of records from the controversial president’s term and a half in office. Most of the information was inconsequential and of no real value other to those with an extraordinary affinity for all things Nixonian. There were, however, among the stacks, a few tidbits that elucidate an already familiar picture of a grumpy old man with a chip on his shoulder and the political power to do something about it.

One of Nixon’s most lamentable legacies is his penchant for putting political foes in their places. Democrats, hippies, minorities, journalists, and others were frequent targets of President Nixon’s wrath, expressed as either active persecution or an arctic cold shoulder. Either way, Nixon and the underlings somehow convinced to carry his water behaved in an implacable and insular manner that climaxed in the ultimate act of self-deception — the Watergate burglary scandal.

A dusting of this cache of paperwork reveals the arches and whorls of deviousness that came to epitomize the Nixon years. One of the early quarries of Nixon’s dirt hunters was Senator Ted Kennedy. For some reason, probably vestigial animosity from the 1960 presidential campaign, Nixon loathed the youngest Kennedy and memos released Monday detail Nixon operatives’ attempts to monitor the dalliances of the late Massachusetts law maker. With the benefit of the perspective afforded observers on the other side of history, it is easy to distinguish the first tell-tale displays of the espionage and manipulation that brought down Nixon’s presidency.

While the genesis of the Watergate break-in is traceable to the tails Nixon ordered on political rivals, the zenith of the events that brought the Nixon presidency to an historic and ignominious end is the investigative reporting of journalists around the country, most prominently Bob Woodward and Carl Berstein of the Washington Post. The memos released Monday (and popular history records) that reporters and television anchormen were nearly universally demonized by Richard Nixon (and by members of his administration), but the two scribes of the Post had a special place reserved in Nixon’s personal hell.

Despite page after page of calumny, there was an attempt by Nixon to offset the perceived bias and ill-will borne him by journalists by recruiting reporters to work as moles inside newspapers and news agencies throughout the country to feed the administration’s party line to the people via the printed page of the “reputable” media. These plants were known as "Chapman’s Friend," the code name for the journalists on the take that would simultaneously provide the reading public with positive news about Nixon and his policies, as well as provide the president with dirt on his rivals and on Democrats down the line nationwide running for office. The first of these flunkies was Seymour Freidin. This yellow fraternity was joined later by Lucianne Goldberg, who some twenty-two years later would achieve notoriety as the literary agent that encouraged Linda Tripp to tape her conversations with the most infamous White House intern and presidential paramour, Monica Lewinsky.

One organization, the aforementioned Washington Post, would not play ball and for that they were a constant burr under the presidential saddle. Nixon’s special counsel, Charles Colson, leaned on lawyers working on the initial public offering of stock for the Washington Post Company to encourage principals to summarily fire editor Ben Bradlee (a key figure in the paper’s investigation of the Watergate break-in and Nixon’s involvement therein) and to fill the paper’s headlines with news sympathetic to the conflict in Vietnam.

The Colson memo, classified as “eyes only” and dated January 15, 1973, warns Charles Ellsworth (the lawyer being worked on to exert influence over the paper) that there was a group of investors "that would buy the Post tomorrow if Mrs. Graham [Katherine Graham, longtime owner of the Washington Post] would like to sell." In her memoir, "Personal History," Graham wrote, "At one point Nixon had a plan to get Richard Mellon Scaife, the conservative Pittsburgh millionaire, to buy The Post."

Colson pressed the point with Ellsworth offering that the best way for the Post to show "some evidence of good faith" was for editors to print "a few obviously friendly editorials on how well the president is handling the Vietnam War, perhaps a firing of Bradlee, and some straight coverage for a change, maybe they could start putting the Watergate back inside the paper where it belongs instead of blasting it across the front pages."

History records the reaction of the Washington Post to Nixon’s water carriers’ threat to club it with clout and frighten it with threats of economic destruction. For five days after the memo was sent, the Watergate scandal — initiated when burglars broke into the Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate office complex — dominated the front page of the Post. As a matter of fact, within a week of Colson’s face to face meeting with Ellsworth, the bungling burglars of Watergate were either convicted or pleaded guilty, and within a month the president’s coterie of supporters’ feverish and futile attempts to cover up Nixon’s involvement in the crime were revealed and the back draft from that conflagration changed history, changed Americans’ opinions of the office of the presidency, and culminated in the shameful resignation of Richard M. Nixon.

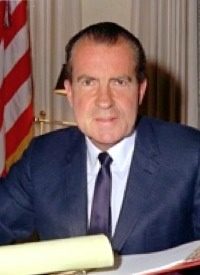

Photo: AP Images