Christianity has proven time and again to be the most resilient force against totalitarianism. This is as true in China today as it was during the days of Stalinist persecution of Christians. Yet some are ever ready to smear Christians with failing to oppose evil. For instance, there has been a spate of books over the last few decades accusing them of indifference or even complicity in connection with the Holocaust — the genocide of more than six million European Jews in Hitler's Germany during WWII. Yet history which was written during the 1930s gives a very different picture of how Christians responded to the evils of Nazism.

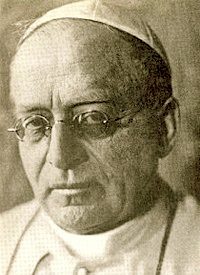

It was 75 years ago, on March 10, 1937, that Pope Pius XI (left) published a papal encyclical entitled Mitt brennender Sorge or “with burning anxiety.” It condemned particularly the Nazi national socialism myth of race and blood — which exalted the Aryan race over all others, leading to the brutal persecution of the Jews, among many others. The encyclical declared that such acts were incompatible with Christianity. Uniquely not written in Latin but rather in ordinary German so that every German could read it, the document was smuggled into Germany and reprinted so that it could be read from every Catholic pulpit on Palm Sunday.

Cardinal Michael von Faulhaber of Munich, a fierce critic of the Nazis, and Cardinal Eugenio Pacelli (who would soon be Pope Pius XII) drafted the document. It hit on every prop of Nazism. It stated that human rights were God-given and transcended national boundaries; that rejection of the Old Testament (one of the principal elements of the Nazi “German Christian” movement) was blasphemous. It explicitly censured “exaltation of race, or of people, or of state, or a particular form of state":

None but superficial minds could stumble into concepts of a national God, of a national religion; or attempt to lock within the frontiers of a single people, within the narrow limits of a single race, God, the Creator of the universe, King and Legislator of all nations before whose immensity they are "as a drop of a bucket."

The Nazis did not condemn the encyclical; they simply pretended that it did not exist. But the day after it was read, the Gestapo visited every diocese in Germany and seized every copy of Mitt brennender Sorge, as well as church printing presses and paper. Every publishing house that had assisted in printing the encyclical was shut down.

Christians in the United States had censured the Nazi persecution of Jews four years earlier. On March 22, 1933, within weeks of the Nazis taking power, a large number of American Christian leaders issued a joint statement of support of the Jews in Germany: “It is the sacred duty of every member of the human family and every supporter of the Christian faith to counteract this subversive, un-Christian and inhuman propaganda.” Two days later, the Review of Greenburg, Pennsylvania, reported: "With all the troubles we have in the United States at the present time, a group of distinguished statesman, clergymen, jurists and layman, all of the Christian faith, have made a strong appeal to the Germans against the persecutions [of Jews]." The same day, the San Francisco Chronicle stated: “If he [Hitler] is open to any reason at all it should give him pause to observe how Americans of all creeds have joined in protest against the blind anti-Jewish fury of his followers.”

In May, 1933 the German government was presented with a resolution signed by 1,200 Christian clergymen from all across America, which read:

We, a group of Christian ministers, are profoundly disturbed by the plight of our Jewish brethren in Germany. That no doubt may exist anywhere concerning our Christian conscience in the matter, we are constrained, alike with sorrow and indignation, to voice our protests against the present ruthless persecution of Jews under Herr Hitler’s regime.

Nazi attacks on Jews in 1933 produced mass meetings of protest throughout the United States by Jewish and Christian organizations. It was said that countless pulpits throughout the Christian world echoed the words of Episcopal Bishop William T. Manning of New York: "None of us, whether we are Jews or Christians, none of us who call ourselves Americans, have the right to be indifferent to such acts." On July 19, 1933, the Catholic periodical called America published an article powerfully condemning Germany's ruthless treatment of the Jews. Two days later the Pacific Coast Theological Conference, an interdenominational body, adopted a resolution also condemning Nazi persecution of Jews.

In September, 1933, Dr. David Bryn-Jones, pastor of the Trinity Baptist Church in Minneapolis, warned that Hitler planned the “annihilation of the Jewish people in Germany.” In October 1933, an international alliance of Protestant churches in 37 nations passed a protest against both the "Aryan Clause" (which prohibited those of Jewish descent from, among many other things, becoming members of Protestant churches in Germany) and the persecution of Jews in Germany. That same month Protestants and Catholics in Minnesota joined to protest Nazi mistreatment of Jews. In November 1933, the YMCA warned its members and affiliates in a national bulletin not to join or support any anti-Jewish organizations.

Christian opposition to Nazi anti-Semitism existed within the Third Reich as well. Pastor Charles MacFarland of the Federal Council of Churches in his 1934 book, The New Church and the New Germany, written while he was in Germany, observed of that country's boycott of Jewish stores: “Pastors and local groups of pastors conferred and sought to exercise restraint. Individual leaders spoke out openly. There is good evidence that the limiting of the official boycott to one day was the result of church intervention.” Dr. Hermann Kapler, President of the German Church Federation, went to Nazi officials to protest the boycott, but he was simply ignored.

Protestant Christians in Germany also opposed Nazi efforts to enforce the Aryan Clause. The Jewish American Yearbook of 1934, published by the Jewish Publication Society of America, announced that on July 13, 1934, “… the reorganized Evangelical Church will not apply the Aryan Clause to its membership and that Christians of Jewish descent will not be expelled from the church.” Three months later 2,000 pastors posted a manifesto in Wittenberg, Germany, protesting the Aryan Clause and declaring it a violation of the Christian gospel.

Pope Pius XI in 1938 stated simply, “How can it ever be possible for a Christian to be an enemy of the Jews? No Christian can have anything to do with anti-Semitism.” The Catholic Bishops in America in 1939 formally deplored anti-Jewish prejudice.

The world, at the time, took little notice of this papal pronouncement, as well as the support of German Protestant pastors for Jews and the unsolicited aid that Christians throughout the world gave to German Jews.

Jews, however, did notice the courage of Christians around the world in defending their persecuted co-religionists. James Waterman Wise, son of the famous New York Rabbi Stephen Wise, in his 1939 book Swastika, the Nazi Terror, stated: “There are few finer examples of religious brotherhood in action than the instantaneous response of the Church to Nazi persecution of Israel.” Rabbi Julius Gordon also described the Christian response against Nazi anti-Semitism: “Never before has Christendom voiced a more potent protest against this un-Christian crusade of human hatred.”

Eva Gabrielle Reichmann, a German Jewish historian whose husband was briefly interned in a Nazi concentration camp but who escaped to England, observed: “The German Catholics, particularly the older generation, who were still supported by these moral props, showed on average a stronger resistance to Nazism and anti-Semitism.” Abram Leon Sachar, another Jewish historian and scholar who was the founding president of Brandeis University, in his 1940 book, A History of the Jews, noted: “Most heartening of all was the sympathy and goodwill of Christian leaders as Hitler’s terror mounted…The millions in money that were raised by Christian friends were no more important than the spirit of goodwill which tremendously bolstered the morale of sorely tried Jewish communities which were condemned to live in the very heart of disaster.”

The Chief Rabbi of Rome, the oldest Jewish synagogue in the world, became a Catholic after the war ended and took his Christian name, Eugenio, to honor Pope Pius XII, the principal author of Mitt brennender Sorge. The rabbi knew just what was in that famous document and what it meant when it was read by courageous priests throughout Nazi Germany 75 years ago.