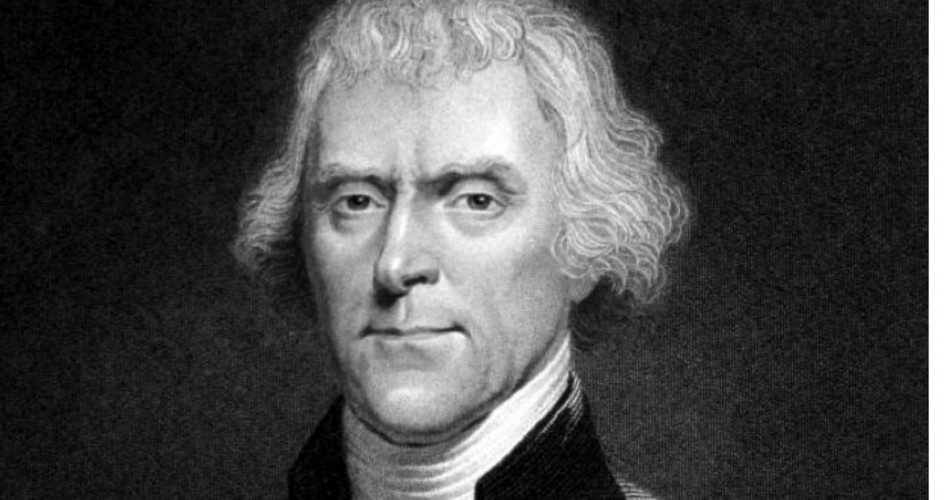

“Many historians now believe the third president of the United States was the father of her six children,” wrote Krissah Thompson, in a recent article for the Washington Post.

The woman referred to is Sally Hemings, a slave of Thomas Jefferson. Thompson’s article was about how the people who run Jefferson’s historic Monticello are restoring the room where “historians believe Sally Hemings slept.”

Thompson’s piece is written as though it is a proven fact of history that Thomas Jefferson fathered at least one, if not all six children of Hemings. But historical scholarship is not a product of a vote by professional historians; it is a matter of evidence.

And with this story, the evidence is sorely lacking.

One is not surprised that a liberal journalist such as Krissah Thompson would promote the narrative that Jefferson parented children through a slave woman; but is certainly disappointing that the caretakers at Monticello, who are supposed to be promoting actual history, have chosen to repeat titillating gossip.

But it is not just at Monticello. It is routinely set forth as an established fact by not only journalists, but by history teachers in classes across the land. This sordid story was even used in a February 6 fundraising letter by the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. In the letter, signed by Mitchell B. Reiss, president and CEO of Colonial Williamsburg, he mentioned the “Freedom Bell — the bell at Williamsburg’s First Baptist Church, one of America’s first African American churches, established in 1776.”

Reiss wrote, “The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation restored the bell, which rang out — for the first time in decades — at the hands of descendants of Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings in celebration of Black History Month.” (Emphasis added.)

For most of the 1700s, Williamsburg served as the center of government for the Virginia Colony (after Jamestown suffered the loss of the state house in 1698). In the 1920s, colonial Williamsburg was restored through the work of many community leaders, the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities, the Colonial Dames, the Daughters of the Confederacy, the Chamber of Commerce, and John D. Rockefeller, Jr.

It is a major tourist destination, where visitors can see what life was like in the early history of the first British colony, and the home of four of the first five presidents of the United States — including Thomas Jefferson.

Sadly, tourists at Monticello and Williamsburg are now being treated to a major distortion of the historical record, for what purposes we can only speculate. But as George Orwell observed, “The most effective way to destroy people is to deny and obliterate their own understanding of their history.”

Certainly there are enough established facts from the life of Jefferson for which he can be justly criticized: a critic of slavery who kept slaves; a man who, at least initially, praised the radicals who brought on the bloody French Revolution; and one who sometimes deviated from his principles of liberty and limited government. But Jefferson was also a man who accomplished great things: He authored the Declaration of Independence — words that still stir not only Americans, but peoples striving for liberty throughout the world.

The charge that Jefferson fathered children by Sally Hemings is not new; it originated during the time that Jefferson was president. But because the rumor was spread by a man of questionable reputation, a known political enemy of Jefferson’s who was infamous for his vicious smear tactics, it was routine for most historians to dismiss the charge.

Jefferson was a widower for more than 40 years, which probably contributed to the credibility of the accusation. In 1976, historian Fawn Brodie made the case in her book Thomas Jefferson: An Intimate History that Jefferson’s supposed affair with the slave girl Sally began while he served as America’s minister to France in the 1780s, when she was still in her teens. Reading Brodie’s arguments gives us some insight into just how far liberal historians are willing to go in an effort to tarnish the reputation of one of the more illustrious of the Founding Fathers.

According to Brodie, Jefferson was really talking about Sally’s smooth mulatto contours in his 25 pages of notes found taken during his 1788 tour of France and Germany. Brodie claimed that Jefferson’s references to the “mulatto soil of the hills and valleys” of those two countries were not really about the soil, but rather his mixed-blood slave concubine.

This ugly accusation received little traction until the release of DNA findings in 1998 in the English journal Nature. The magazine article reported that a DNA “match” of a male descendant of Sally’s son, Eston Hemings, and a “Jefferson male,” were presented as the proof of a nearly 200-year-old rumor of Jefferson’s sexual relationship with his slave girl.

Interestingly, the DNA actually cast serious doubt on the decades-old charges of Jefferson’s political enemy, James Callender. Callender wrote in a Federalist Party (Jefferson’s party was called the Republican Party, later to split into the Democratic-Republicans and the National-Republicans) newspaper that one of Jefferson’s “children” by the “wench Sally” was named Tom. Thomas Woodson, thought to be the “Tom” referred to by Callender, was conclusively proved by DNA testing not to be Jefferson’s descendant.

Jefferson biographer Dumas Malone expressed amazement that any real scholar could give serious consideration to Brodie’s book. But Brodie’s thesis convinced some descendants of Sally Hemings and some descendants of Thomas Jefferson’s uncle to submit to a DNA test. In a scientific DNA test, the samples must come from those in the direct male line, or male-to-male all the way from the person in the distant past to the present. However, no DNA from Thomas Jefferson was possible, as he had no living “direct male” descendants.

Because DNA could not be obtained from a direct descendant of Thomas Jefferson, DNA samples were taken from a direct male descendant of Thomas Jefferson’s uncle, Field Jefferson. Another sample was obtained from direct male descendants of Eston Hemings, Sally’s youngest son.

The tests allowed a conclusion to be made that Eston Hemings was, indeed, the child of a male member of the Jefferson family. This revelation that Eston was descended from a “Jefferson male,” or someone closely related to Jefferson’s uncle, Field Jefferson, created an immediate sensation.

The family of Eston Hemings had long heard a family story that they were descended from a Thomas Jefferson “uncle.” But like many family history stories passed down through the generations, they often contain some truth mixed with some embellishment or misunderstanding. In this case, it was not possible for Field Jefferson to have fathered Eston, because Field died several years before Eston’s conception. Another paternal uncle of Jefferson’s had likewise died years earlier.

The commission which conducted the DNA work concluded, “After a careful review of all the evidence, the commission agrees unanimously that the allegation [note: the charge that Thomas Jefferson was the father of Eston Hemings] is by no means proven; and we find that it is regrettable that public confusion about the 1998 DNA testing and other evidence has misled many people.”

Unfortunately, the media chose not to report these conclusions accurately, and journalists since that time have repeated this sloppy work, leading to the widespread perception that Thomas Jefferson essentially committed statutory rape of a teen-age girl in Paris, continued the affair for several years after his return to Virginia, and fathered several more children by a slave woman, over whom he exercised legal control.

Dr. Eugene Foster — who conducted the DNA tests by using five male-line descendants of Jefferson’s uncle, Field Jefferson, and one male-line descendant of Eston Hemings, the youngest child of Sally Hemings — later wrote that he was “embarrassed by the blatant spin of the Nature article.” He stated, “The genetic findings … do not prove that Thomas Jefferson was the father of one of Sally Hemings’ children…. We have never made that claim.” He added, “My experience with this matter so far tells me that no matter how often I repeat it, it will not stop the media from saying what they want to.”

Yet, if the DNA indicated that a male of the Jefferson line was the father of Eston, then who else besides Thomas Jefferson is a logical candidate as the father?

The Jefferson Foundation noted, “Dissenters have pointed to Jefferson’s younger brother, Randolph Jefferson, as a candidate for paternity, a possibility that would fit the DNA finding.” It should be reiterated that the DNA findings were not that Thomas Jefferson was the father of Eston Hemings, but rather that a “Jefferson male” was an ancestor.

Randolph Jefferson had earned a reputation for socializing with Jefferson’s slaves, and was expected to visit Monticello approximately nine months before the birth of Eston Hemings.

Until 1976, the descendants of Eston Hemings believed they were descended from a Jefferson “uncle.” While Randolph was Thomas’ brother, not his uncle, this is the type of confusion found in family stories. Randolph was known at Monticello as “Uncle Randolph,” because, of course, he was the uncle of Thomas Jefferson’s children by his late wife. According to Martha Jefferson Randolph, her father’s younger brother was “Uncle Randolph.”

Clearly, the advocates of the proposition that Thomas Jefferson fathered Sally Hemings’ children must strain the evidence to reach this conclusion. For example, Jon Meacham, in his book Thomas Jefferson: The Art of Power, said that one “suspects” that Jefferson was “in his imagination” thinking of Sally when he saw the painting of Abraham and his servant woman Hagar during his visit to Dusseldorf while in Europe! This is what passes for the reasoned judgment of historians?

Jefferson’s political opponent, John Adams, did not believe Callender’s ugly accusations had any credence, dismissing them as “mere clouds of unsubstantiated vapor.”

Noted historian Forrest McDonald, who was a devotee of the greatness of Jefferson’s arch-nemesis, Alexander Hamilton, was once inclined to believe the rumors, but after carefully reviewing all the evidence, including the 1998 DNA findings, concluded, “I’m always delighted to hear the worst about Thomas Jefferson. It’s just that this particular thing won’t wash.”

Yet, in spite of such flimsy evidence, journalists and some historians, who should be a great deal more responsible, have opted to put forward this libel about Jefferson as a proven fact.

Steve Byas is a professor of history at Randall University in Moore, Oklahoma. His book History’s Greatest Libels analyzes some of the unfair accusations that have been made against several individuals in history, including Christopher Columbus, Joseph McCarthy, and most recently, Clarence Thomas.