Social and political revolutions often follow defeat on the battlefield, and so was the case with Germany in the wake of World War I. By the summer of 1918, it was apparent that Germany had lost the war. Even the absurdly optimistic reports from the High Command could not hide the fact that the German Army would not prevail on the field of battle. Five years of warfare in which soldiers from both sides were sacrificed in meat-grinder-like assaults on entrenched positions had nearly wiped out an entire generation of German men. Since arriving in France in 1917, American troops had tilted the balance of power in favor of the Allies, and it was only a matter of time before the Yanks would turn the tide.

Choked by an Allied blockade that threatened starvation at home, and battling a loss of confidence in Kaiser Wilhelm II, the army readied itself for defeat. In order to deflect responsibility for defeat, army leaders handed over power to a civilian government under Prince Max von Baden in October 1918. The beginning of the end came when the German naval command, as part of a last-ditch effort, ordered the fleet at Wilhelmshaven to engage the British fleet — a ludicrous command that compelled the majority of sailors to mutiny. Demonstrations at Kiel, Germany, on November 3, 1918, ignited a larger mutiny and soon soldiers, sailors, and workers from all over Germany were organizing local “soviets” in order to take control of local governments. Senior Prussian officers no longer controlled the army, but in what became a characteristic of the “1918 revolution,” mutineers and erstwhile revolutionaries generally maintained order in their ranks. In many cases, junior and non-commissioned officers were elected to lead defeated or mutinous units back home. It was, in the end, perhaps the most ordered military collapse in the history of warfare. Carl Zuckmayer, a young German officer commenting on the scene, wrote, “Starving, beaten, but with our weapons, we marched back home.”

Revolution

Horrific losses in France’s Argonne Forest region put the final nail in the coffin, and on November 9, 1918, a cease-fire was announced, and General Wilhelm Groener ordered what remained of the army to withdraw from the front lines. The kaiser’s abdication followed quickly and Prince Max von Baden, who had been acting as chancellor since October, handed power over to Social Democrat leader Friedrich Ebert.

A republic was quickly declared, but its form was completely unknown at the time. In any case, the new “republic” had to quickly deal with a host of problems including signing an armistice, demobilizing an army, and gaining control of a growing revolution. The kaiser’s abdication forced other German crowned heads to do the same. But unlike the Russian Revolution, where the communists spilled the blood of royalty, and delightfully shot Tsarist army officers, this German revolution maintained the strange sense of decorum that characterized the unit mutinies a month earlier. They would not repeat the brutality that the Bolsheviks had visited upon the Tsar and his family. These revolutionaries displayed their anger by merely cutting off officer rank insignia rather than resorting to lynching, as was the fashion in Russia. Unnerved by an orderly crowd, an old Berliner was heard to remark, “I don’t like these peaceful revolutions at all. We shall have to pay for it some day.”

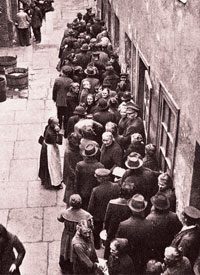

Soldiers wearing red arm bands signifying them as socialists or “reds” began to stream into German towns, and as the German army returned home it was demobilized in short order. Workers’ and soldiers’ councils sprouted up initially in Hamburg, Cologne, and Wilhelmshaven, and they soon spread throughout the country. A few of these groups were considerably radical, but many were born of a desire to end the war and protect local communities from a capricious transitional government. Still, there was no doubt among the citizenry that a revolution had taken place.

Between October 1918 and March 1919, Germans endured revolutionary activity across the country as Marxists, socialists, and nationalists each vied for power and influence. Taking advantage of the situation, Marxists sought to overthrow capitalism and establish a proletarian state. They had earlier broken with the Social Democrats (SPD) and they now looked to appropriate the revolutionary movement.

Even before the armistice was signed on November 11, SPD party leader Kurt Eisner and his followers seized control of Munich and declared it a Bavarian Republic. Just as Friedrich Ebert of the “moderate” Social Democrat Party was declaring a new democratic republic on November 9, 1918, Karl Liebknecht of the Independent Socialists (USPD) was poised to declare the establishment of a new socialist republic with support from the revolutionary masses. Ebert knew that he needed the support of at least a small number of Independent Socialists in order to head off Liebknecht’s push for a socialist republic. He got the support he needed with the formation of a Council of People’s Commissars consisting of three USPD leaders and three from the SPD. Liebknecht had been stymied.

Later that day, Ebert received a call from General Groener at army headquarters in Spa. It was then that Groener told Ebert that the kaiser had left Germany for Holland, and that he wished that the new government would lend support to the officer corps, and the Prussian military tradition, as it maintained order in the ranks. Groener also offered Ebert the support of the army if Ebert would help resist Bolshevism by quelling the activities of some of the more radical soldiers’ and workers’ councils. Ebert hated Bolshevism as much as Groener; he preferred a constitutional monarchy, and in the end he pledged the new government’s support in exchange for the army’s assistance in combating the Bolshevik challenge.

On November 11, 1918, the armistice was signed between German and Allied representatives. The war was finally over and a new fledgling government was in place.

The period between the armistice and the elections for the National Assembly in January 1919 was marked by tension between the SPD and the USPD, the latter being constantly influenced by hard-left Marxist elements within the group. Ebert spent most of his time governing the transition from a war-time economy and finding ways to alleviate the economic hardships of the average German. Meanwhile, Marxist agitators spent their time marching in the streets and planning uprisings. During December 1918, Ebert’s SPD clashed with Liebknecht’s newly formed Spartakusbund, leaving 16 dead in the streets. In January 1919, the Spartacists attempted to overthrow the government but were crushed by the army and Freikorps troops — volunteers raised by individual army commanders. The failed uprising ended with the murders of Liebknecht and his close ally, Rosa Luxemburg.

Workers’ demonstrations and small-scale disturbances continued, but the army and the Freikorps ensured that the new republic would not veer sharply left. The National Assembly elections on January 19, 1919, enjoyed an 83-percent turnout that included, for the first time, women over 20 years of age. Ebert’s SPD party secured 38 percent of the vote, with the Catholic Centre Party getting almost 20 percent. Nationalist and monarchist parties secured less than 15 percent of votes cast. In February, delegates elected Ebert as the first president of the republic in the town of Weimar, from whence the new government took its name.

Challenges

Nothing influenced the new Weimar Republic and the subsequent history of Germany more than the peace settlement signed at Versailles. Foreign Minister Count Brockdorff-Rantzau would lead the negotiations for Germany. Earlier, he had been one of the few who had supported a compromised peace in 1917, and he was confident that he would secure an honorable and lenient peace from the Allies. Brockdorff-Rantzau was counting on the Bolshevik threat and Wilson’s Fourteen Points to enable Germany to remain a viable European power. He knew that there would be some territorial concessions, but he was not prepared for what would ultimately transpire at Versailles.

In the wake of four years of brutal warfare that had destroyed large areas of France and Belgium and resulted in the loss of millions of lives, the Allies were in no mood to proffer lenient terms. Germany would lose huge areas of land, including Alsace-Lorraine to France, and most of West Prussia, Upper Silesia, and Pozen to the newly formed Poland. Danzig would become a “free city” under the newly created League of Nations, and Germany was to lose all of its overseas colonies. The infamous 231 “war guilt clause” shifted the blame for the war entirely to Germany, and Germany’s army was reduced to 100,000 volunteers. Its navy was to be limited, and entry into the League of Nations was forbidden. More devastating, particularly for a country emerging from a costly war, were the unspecified reparations forced upon Germany. By May 1921, Germany was required to make payment of 20 billion gold marks as an interim payment. On May 12, SPD Prime Minister Philip Scheidemann declared, “What hand must not wither which places these fetters on itself and on us?”

But for the Allies, these terms seemed just. Anti-German feeling ran very high, particularly in the European countries that had suffered at the hands of the Hun. It was time to make them pay, and that feeling dominated the political scene for years after the war, particularly among the French, who no doubt had had enough of German militarism. Sadly, had the Allies not taken this approach, and instead had looked to ways to support an evolving German political institution, Hitler might never have come to power. Defeat, coupled with the harsh reality of Versailles, was a traumatic experience for Germany. It reinforced the sense of betrayal — “the stab in the back” allegedly perpetrated by Jews and socialists that had ultimately defeated the supposedly unbeaten German army, and the reparations issue became a rallying point for nationalists.

Occupation and Hyperinflation

By 1920, political and economic questions related to the reparations issue were becoming a serious concern. How could a weak German economy address the unimaginably high level of reparations? Germany had financed the war through loans and bonds (sound familiar?). Inflation was already present when Joseph Wirth’s government pursued a policy that further fueled inflation between 1921 and 1922. Wirth’s policy was designed to show that Germany could not meet its reparations payment responsibilities. By printing more paper money, Wirth initiated a plan in which Germany would make reparations payments in increasingly worthless marks. Better to pay in cheap worthless marks, so Wirth thought.

The Allies, particularly the French, had other ideas. On January 9, 1923, the French used a shortfall in German coal deliveries as a pretext to invade and occupy the Ruhr region of Germany. Their aim was to “supervise” production of the coal that was part of the reparations deal struck at Versailles. Payment of reparations “in-kind” would now be seized at its source. In the eyes of the French, anything that weakened Germany was a benefit to France. The Weimar Republic responded to the invasion by advocating passive resistance. Industrialists were ordered not to comply with French orders or to hand over any coal stocks.

A government-backed general strike was called in the Ruhr, and was financed entirely by the printing of even more paper money. Fearing the loss of capital, credit was extended to factory owners so that they might keep their operations running during the general strike. The loss of earnings, however, exacerbated the situation and led to spiraling hyperinflation. Within six months, the currency completely collapsed. With it went all confidence in the republic. Fear and panic followed as millions of Germans found themselves in financial ruin. In August 1923, one dollar was worth 4.6 million marks. Three months later it was worth 4,000 billion marks! To keep up with the pace of inflation, 133 printing offices pumped out marks for the Reichsbank. Ordinary items like bread cost millions of marks. It was impossible to keep up with the pace of inflation but the Reichsbank tried by increasing the money supply — a move that made the situation even worse.

By October it cost the Reichsbank more to print the notes than they were worth. This completely irresponsible and cataclysmic action wiped out savings accounts, personal annuities, stocks, and pensions. While the middle class was being destroyed, industrialists and large businesses benefited from the devaluation of the currency. Those businesses that had issued stock found it easy to pay off their debts with worthless currency at a “mark equals mark” ratio. By November 1923, workers were being paid five times a week, real wages were down 25 percent, and banks were issuing notes by their weight.

Hyperinflation brought with it new, more ominous signs of social degradation. The German generation that valued thrift and fiscal responsibility now dealt with a situation in which plummeting home values destroyed the very concept of savings. Years of saving and scraping to purchase stability through home ownership went for naught and the lesson was not lost on a younger generation that now saw saving as a pointless endeavor.

A youthful generation set adrift from traditional moorings naturally gravitated to immorality. Marriage was no longer an economically secure arrangement. Consequently, the commercial sex industry bloomed, particularly in Berlin. Klaus Mann, son of the author Thomas Mann, later described an encounter with a Berlin prostitute. “One of them brandished a supple cane and leered at me as I passed by,” wrote Mann. The exchange ended when the prostitute offered her services for “six billion and a cigarette.” Seeking pleasure in activities that had formally been eschewed in favor of virtue became commonplace. Stefan Zwieg, a contemporary of Klaus Mann, summed up the Weimar mood thusly:

It was an epoch of high ecstasy and ugly scheming, a singular mixture of unrest and fanaticism. Every extravagant idea that was not subject to regulation reaped a golden harvest: theosophy, occultism, yogism, and Paracelcism. Anything that gave hope of newer and greater thrills, anything in the way of narcotics, morphine, cocaine, heroin found a tremendous market; on the stage incest and parricide, in politics, communism and fascism constituted the most favored themes.

Passive resistance in the Ruhr was called off in September, but not before the damage had been done. The new German state was in danger of falling as extremist groups like Adolf Hitler’s National Socialist German Worker’s Party (NSDAP) maneuvered for power. Inflation primed the pump of aggression and political extremism. A number of Marxist groups had threatened unrest in Saxony and Thuringia, and Hitler used the opportunity as a call to arms in a Munich beer hall. Hitler’s secondary aim was to attain Bavarian autonomy.

Impressed with Mussolini’s “March on Rome” in 1922, Hitler planned his own “March on Berlin.” In November 1923, Hitler seemed on the verge of success when some of his powerful supporters in Bavaria retracted their support for the former army corporal. The Nazi putsch failed after some of Hitler’s supporters were shot in front of Munich’s Feldherrnhalle. Hitler was arrested and endured a short trial in which he received some public notoriety. After conviction, he served but a few months of a five-year sentence in relative comfort at Landsberg prison. It was there that the architect of the Holocaust wrote Mein Kampf — the little book that would lay out his twisted political ideology.

Stabilization and the Fall

Eventually the German currency was stabilized, but at a great cost. Unemployment was rampant, wages dropped, and high prices dominated the market. But by 1924, it appeared that the problems of the early republic were over. Foreign Minister Gustav Stresemann successfully regularized foreign relations with the Western Allies. In 1924, the Dawes Plan married American economic interests with Germany, and reparations arrangements became more manageable. In 1925, the hated French began leaving the Ruhr, and by 1927, the disarmament commission was withdrawn. By 1930, the Rhineland was to be cleared of any foreign occupation. Under Stresemann, Germany had made remarkable progress on the foreign-policy front, but there were other problems on the horizon for the new republic.

A specter of national decline sapped the strength of the republic. Fewer and fewer young people supported the Weimar system; they were often more concerned with drinking and dancing. Indeed, one of the unfortunate outcomes of the First World War was that many youths of 1920s Germany grew up without fathers. The traditional ties that tethered the young to their families and communities were torn asunder by the war and the post-war upheavals. Weimar Germany was a liberating experience for young Germans, but they increasingly began to see the government as dominated by prewar political parties. The SPD and the Catholic Centre Party seemed stodgy and not capable of instituting the rapid social change that enamored Germany’s youth. By the late 1920s, most German youths were more likely to identify themselves with the Communists (KPD), or the Nazi Party. They were simply bored with what Goebbels described as an “old men’s republic.”

Constant concessions to the left by weak governments fueled nationalist fervor. The hyperinflation debacle had also sapped much of the middle-class support for the republic. As today, those people saw the value of their homes and savings decline while debtors seemed to benefit from the easy-money policies of the Weimar Republic. Leftists, too, had much to complain about. For them, the republic had betrayed its socialist roots.

Despite seeming stabilization, the social, political, and economic problems that plagued the new republic never disappeared. Much of it was self-inflicted — the devaluation of its currency in order to punish the French, costly welfare schemes included in the state constitution, ineffective coalition governments, and an ongoing yearning for the old days of Imperial Germany combined to set the stage for its failure. Finally, a worldwide depression and the rise of a charismatic leader put an end to the ill-fated republic.

Although not in exactly the same position as Weimar Germany, the United States now finds itself under the rule of its own charismatic leader and a Federal Reserve that together seem bent upon debauching our currency through inflation. By “priming the pump” in super Keynesian fashion, the Obama administration courts an economic disaster that could make Weimar Germany look fiscally sound.