On June 19, 1865, Major General Gordon Granger led Union troops to Galveston, Texas, and announced the Civil War was over, and the slaves were now free. He read General Order Number Three: “The people of Texas are informed that in accordance with a Proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolutely equality of rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and free laborer.”

This understandably led to jubilation among many of those who had been held in slavery. Some, especially older slaves, simply remained as employees on the farms and plantations of former masters, while others, mostly younger people, took off to seek employment elsewhere. For many in the South in the aftermath of the War Between the States, whether former slave or other southerners, black or white, the harsh reality was that almost all faced a grim economic future.

But at least they were free, and that was certainly something to celebrate.

Juneteenth, however, as a day to mark the “end” of slavery in the United States, has always been a puzzle. General Granger based his general order on a proclamation from President Abraham Lincoln who had been dead since the middle of April. The Emancipation Proclamation itself went into effect on January 1, 1863, two and one-half years earlier, and was of dubious constitutionality.

Lincoln’s executive order, issued with a claim of authority as commander-in-chief of the armed forces of the United States, has contributed greatly to a misunderstanding of what the issue was over which the Civil War was fought, what ended slavery in the United States, and what were the motivations of the soldiers who fought in the deadliest conflict in American history — claiming well over 600,000 lives.

It is commonly believed today, contrary to historical accuracy, that the North and South simply lined up and fought a four-year war to settle the issue of slavery, with Union soldiers fighting a great crusade to end slavery and Confederate soldiers ready to die to “keep their slaves.”

Slavery certainly was a major contributing cause to the secession of seven Southern states — Alabama, Georgia, Florida, South Carolina, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas — but to say that the war was fought to end slavery or to keep it (depending on one’s side of the war) is just not true. Other factors contributed to the secession of these seven states — the tariff, which largely benefitted the Northern states and was a largely a detriment of the states in the South, for one. Northern states had, more than once, threatened secession early in U.S. history, mostly due to resentment at the outsized influence of Virginia in the Union. At that time, no one said there should be a civil war to force New England states back into the Union, if they did secede.

Later, in the 1830s, when South Carolina announced it would refuse to collect the tariff, and President Andrew Jackson asked Congress for authority to use force to make sure it was collected, and war loomed, slavery was not even an issue at all.

In other words, secession was not a purely Southern threat, and slavery was not the only issue of dispute between North and South in the years before the Civil War.

But it was cited as an issue when South Carolina seceded on December 20, 1860, following the election of Abraham Lincoln as president. After several weeks of negotiations, during which time Lincoln said that he had no intention of doing anything about slavery in the states that had seceded, Fort Sumter, in the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina, was taken by the newly formed Confederate States.

Without getting sidetracked into discussing the entire Fort Sumter episode, President Lincoln’s response was to call for 75,000 volunteers for the purpose of making sure federal laws (essentially the collection of the tariff, the main source of revenue for the U.S. government) were enforced in the seceded states. Lincoln did not call for an invasion of the South to free the slaves. Had he done so, he most likely would have touched off riots in the North. He certainly would not have had the overwhelming response of enlistments that he did have. Most Northern men who enlisted believed that the dissolution of the Union would be detrimental to the cause of liberty in America. They did not enlist in some crusade to free the slaves.

At the time of Lincoln’s call for volunteers, more slave states were still in the Union than out. Had he intended to fight a war to end slavery in the entire country, he would have had to invade states that had remained in the Union. This powerfully demonstrates the absurdity of the notion that the war was fought “to end slavery.”

Yet when Lincoln made his call, those slave states still in the Union were expected to produce volunteers to invade the Deep South. This quickly precipitated the secession of four more slave states — Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Arkansas — states that had previously rejected secession. They did not secede to protect slavery, but rather because of Lincoln’s call for an invasion of fellow states. Three other states — Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri — all slave states, did not secede, but did eventually provide soldiers for both sides. Again, had the war been fought to “end slavery,” one would think that they would have seceded, as well. Slavery was still legal in Delaware, but secession was never seriously considered there.

As the war dragged on, with Confederate troops winning more battles than they lost, it began to look as though the Confederate States of America would become an independent nation. By the fall of 1862, France and Great Britain were poised to recognize this as a fact. Lincoln was desperate to “save the Union,” and took a desperate measure. He could have told the British that they should not recognize the independence of the Southern states because they had no right to secede from the Union, but the Brits would have probably just laughed, and said, “Serves you right,” (considering what had happened in 1776).

Both the French and the British had abolished slavery a few decades earlier, and undoubtedly Lincoln could have kept both countries from recognizing Southern independence if he would have made the war about slavery, rather than the legality of secession. But had he done so, he might have faced desertions from the Union army. More importantly, this may have necessitated the invasion of four Union states where slavery was still legal.

Lincoln’s solution was to “thread the needle.” He would issue an executive order, ending slavery in states “still in rebellion” on January 1, 1863, as a “war measure,” but leaving slavery untouched in those states still in the Union. Combined with the Union military success at Antietam in September 1862 in blocking General Robert E. Lee’s invasion of Maryland, the British and the French decided to hold off on recognizing the South.

The reality is that Lincoln had no constitutional authority to end slavery anywhere, but his Emancipation Proclamation proposed to leave slavery untouched in areas that recognized his presidency, and end it where he had no troops to enforce it.

Despite the inherent contradictions of the Emancipation Proclamation, it has led many today to believe that the war was fought to end slavery, and slavery was ended by it.

It also has slandered the hundreds of thousands of Confederate soldiers who fought in the war, with many today damning their own ancestors as having fought to “keep their slaves.” The reality is that only a tiny minority of Confederate soldiers even owned any slaves, and almost none were fighting to save the ugly institution.

So why did they fight? To stop an invading army, of course. Early in the war, some Union soldiers asked a captured Confederate soldier why he was fighting. He answered, “Because you are here.” In other words, had there not been Union soldiers there to fight, there would have been no war.

This is not to address the issue of whether the war was justified by the Union side, but a blunt statement of fact. Confederate soldiers fought to defend their homeland from invasion. It is ludicrous to think that 15,000 men charged across the field at Gettysburg in “Pickett’s Charge” thinking, “I am doing this to keep my slaves,” when hardly any of them had any slaves.

If the Emancipation Proclamation did not end slavery, and the war was not fought to end slavery, what then did end slavery? The truth is, while the war was not fought to end slavery, it did indirectly result in its demise. Early in 1865, the Confederate Congress voted to accept the enlistment of slaves into the Confederate army, with a promise of emancipation. Once that was done, slavery was a mortally wounded institution.

The legal end of slavery was a result of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution, ratified on December 6, 1865. If any date were to be used to celebrate the end of slavery in America, that should be the date.

It is also instructive to addressing the question of whether the war was fought to end slavery. If that were the case, then why was the 13th Amendment even necessary? According to the school of thought that the war was fought to abolish slavery, then the issue had already been settled on the battlefields of the war.

As it was, the U.S. Senate (with the Confederate states not voting) passed an amendment to the Constitution in April of 1864 to abolish slavery. In the House of Representatives, the proposed amendment failed. Even with no Confederate states represented in Congress, an amendment to abolish slavery failed in the House.

At this point, Lincoln offered federal jobs and other inducements, and finally after weeks of arm-twisting, finally obtained passage in the House on January 31, 1865. Again, if the war was fought to end slavery, why was an amendment to the Constitution even necessary?

Interestingly, 10 states where slavery had been legal — including eight formerly Confederate states — voted to ratify the 13th Amendment, without which the proposed amendment would have failed. The Union state Delaware, where slavery was legal until the ratification of the 13th Amendment, refused on February 8, 1865 to ratify it (although they finally did go ahead and ratify — in 1901!).

Other states initially rejecting the 13th Amendment included New Jersey, Kentucky, and Mississippi.

Regardless of why slavery is no longer legal, we can celebrate that slavery no longer exists in America. But we should also reject the multitudes of myths about its demise, myths created and perpetuated to advance certain agendas, rather than to present an historically accurate picture.

Happy Juneteenth!

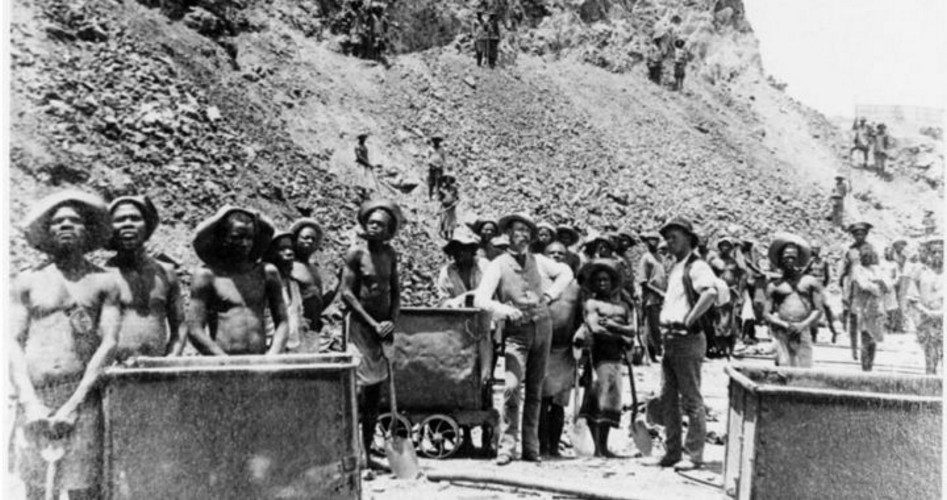

Photo of slaves: Clipart.com