As we honor the Declaration of Independence of the 13 colonies from England, it is critical that if we are to continue enjoying the benefits of that brave decision, we must fully reclaim the rights that are once again being threatened by a burdensome central government.

We must unite as our forefathers did in courageously calling out the despotic deeds of the legislative, executive, and judicial branches. We must exercise our rights to derail the “long train of abuses” that every year grows longer and longer and speeds faster and faster down the track of tyranny.

This year, though, rather than enumerate the “repeated injuries and usurpation” that we have suffered for so long, I want to write about a particular phrase from the Declaration of Independence — the “pursuit of happiness.”

Most Americans familiar with the history of their country are aware of the influence of John Locke on our founding generation. Locke’s famous trivium of fundamental rights — life, liberty, and property — animated our ancestors in their efforts not to revolt against a government, but to “dissolve the political bands” that connected them to tyranny and to restore the right of self-government.

But when it came time to draft the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson (the principal author) called an audible and switched the third of Locke’s threesome, replacing “property” with “pursuit of happiness.”

Why did he make that historic change?

A few years ago, I made a goal to read all the books the Founders read. I searched online and found lists of books they referenced and looked in the indices of the Federalist Papers, the letters written by so-called Anti-Federalist, and the collected works of all those in the first rank of the pantheon of American Founders.

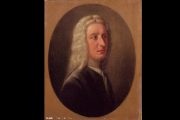

During this quest I repeatedly came across the name of Jean-Jacques Burlamaqui. This was a name I’d never heard before, but it’s a name I cannot ever forget. A bit of biography of the nearly forgotten but immeasurably influential writer is in order.

Burlamaqui was born on June 24, 1694 in Geneva, Switzerland. He was familiar with the works of Samuel von Pufendorf, as he was a disciple of Jean Barbeyrac, the eminent editor of Hugo Grotius and Pufendorf. His mentor encouraged him to study the works of his contemporaries and adjust them to the world as he sought fit.

Burlamaqui dutifully followed his master’s advice and at the age of 25, his skill in internalizing and cogently and coherently restating the theories of natural law was so advanced and well regarded that he was appointed a professorship of ethics and the law of nature at the University of Geneva.

Before assuming this distinguished post, however, Burlamaqui traveled throughout Europe seeking enlightenment on these subjects from some of the greatest lights alive.

To his credit, Burlamaqui, for all his notable achievements and skill, recognized that he would be of greater service to his pupils and to the world at large if he were to dedicate himself to the acquisition of learning and insight from those more advanced, well versed, and accomplished than himself. This humility and clear thinking would serve the young schoolman well as he set his feet on a course that would bring him fame and respect from scholars, thinkers, and most importantly, American patriots.

Two of Burlamaqui’s works left an immense imprint on the minds of American political thinkers who were to become the architects of the world’s most enduring Republic.

James Madison, Thomas Jefferson, and Alexander Hamilton all considered Burlamaqui an example of remarkable clarity of thought and breadth of understanding. Burlamaqui’s two influential books were Principles of Natural Law (Principes du Droit Naturel), published in 1747, and Principles of Political Law (Principes du Droit Politique), published posthumously in 1751.

The learning and admonitions set out in these books were published to the world just in time to be of significant influence on the education of our Founding Fathers.

Burlamaqui’s words and the spirit of his explanations of the laws of man and nature were digested and then quoted liberally by James Madison, Thomas Jefferson, and the like. In fact, all our revered Founders eagerly gleaned insight from the pages of Burlamaqui’s magnificent contribution to the natural-law canon.

Of all Burlamaqui’s American students, Thomas Jefferson was probably the most devout. It was his reading and distillation of Burlamaqui’s theories that inspired Jefferson’s most famous phrase: “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,” though Jefferson restated the principles of natural law he learned from his study of Burlamaqui.

Burlamaqui’s words swayed Jefferson and fellow founder James Wilson to list “happiness” as a natural right as opposed to the more familiar denomination of “property,” also convincing Jefferson that while the designation of property as an “unalienable right” was politically uncertain, it was philosophically well grounded. With Burlamaqui as support, Jefferson felt confident to include the phrase in our nation’s bold Declaration of Independence from England.

Jefferson and Madison held Burlamaqui in such high regard, in fact, that they included his Principles of Natural and Politic Law in their list of books that should be included in the first Library of Congress.

The particular edition recommended by Jefferson and Madison was a translation by Thomas Nugent published in London in 1752.

Burlamaqui claimed the pursuit of happiness was the root motivation of all human actions. People, he insisted, naturally desire that which will afford them the greatest degree of happiness. Based on that observation, Burlamaqui inferred a natural right to pursue happiness. He wrote: “Natural liberty is the right which nature gives to all mankind, of disposing of their persons and property, after the manner they judge most convenient to their happiness…. To this law of nature there is a reciprocal obligation corresponding, by which the law of nature binds all mankind to respect the liberty of other men.”

Burlamaqui believed that the best government was that which interfered as little as possible in the lives of individuals, leaving them free to use their reason to pursue their happiness, however they defined it.

It is true that Jefferson was a man of unequaled erudition. He drank from many wells of wisdom. The imprint of Burlamaqui on the Declaration of Independence is recognized as undeniable by scholars of that momentous document.

The historian Ray Forrest Harvey, in his biography of Burlamaqui, researched the road from Burlamaqui to Jefferson regarding the “pursuit of happiness” and his findings are persuasive:

Burlamaqui as one source for the phrase, “pursuit of happiness,” and its underlying philosophy rests upon a number of factors. Jefferson owned a copy of Natural and Politic Law. It is conceded that George Wythe, with whom Jefferson studied law, was familiar with the work. In all probability Dr. Small, one of Jefferson’s mentors, was acquainted with it. In reading and copying Wilson’s pamphlet he imbibed freely the doctrine of Burlamaqui. Moreover, the concept was a rather common one in the thought of the period. The similarity of the concept with that of Burlamaqui is unmistakable. This has been noted by Fisher in his study of this period. Professor Corwin declares a striking likeness.

However, he is of the opinion that the immediate source of the phrase was Blackstone. If this should have been the case, it came originally from Burlamaqui. In the early portion of the Commentaries Blackstone copied liberally from Natural and Politic Law. Sir Henry Maine has charged that Blackstone copied “textually” from Burlamaqui. Again, granting that Jefferson took the idea from Wilson’s Considerations, it must be remembered that Wilson copied and cited Burlamaqui as an authority for the concept. Upon the evidence at hand it is submitted that the original of the phrase “pursuit of happiness” is Natural and Politic Law.

We should pause today and ask ourselves, if Burlamaqui (along with othersj) was such a powerful influence on our Founding Fathers, why has his name (and those of so many others) been completely obliterated from the curricula of high schools and universities? Is it because a return to a study of these seminal studies of natural law might inspire a new generation of Americans to know and reclaim the rights granted to them by their Creator?

So, today, as we celebrate the courage of our Founders in “assum[ing] among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them,” let’s take a moment to drink a little from the rich streams of natural law theory that taught them how to protect the liberty they treasured.