A Google search of the word “treason” reveals most of the results use the word in context of applying the label to President Obama’s program of nationalizing significant sectors of the American economy. There was a time in our nation’s history, however, when one of our finest patriot fathers is said to have waved the saber of “treason” in the face of the world’s most powerful monarch. And, in return, his fellow Burgesses exclaimed that the patriot was committing treason. That brave (some would say, given the circumstances, reckless) man was the incomparable Patrick Henry.

The silver-tongued orator was never at a loss for words, and he spoke with a ready arsenal of logic. Biographer William Wirt said of him in 1817, “Tis true he could talk — Gods how he could talk!” Lord Byron called him the “forest-born Demosthenes.”

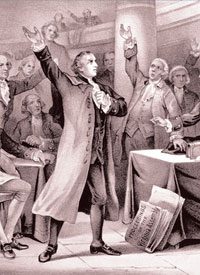

The event that evoked the cries of “treason, treason” — and that more than any other guaranteed Patrick Henry’s place in the pantheon of American heroes, even more so than his famous “Give me liberty, or give me death” speech a decade later — was his key role in opposing the Stamp Act that played out in the Virginia House of Burgesses in 1765.

The Stamp Act

In March of 1764, Parliament expressed its intention to impose a tax on stamps and other documents sold in the American colonies. News of the proposed taxes reached Virginia in the summer of 1764. The Assembly was not then in session and would not be until October 30. Although the Assembly was in recess, the Committee of Correspondence ordered Virginia’s agent in England to oppose passage of such resolutions. On November 30, 1764, a special committee of the House of Burgesses reported a draft of an official response to be sent to the King and Parliament. On December 14 of the same year, the following resolutions were adopted:

1. That an address be sent to the king asking his protection in their natural and civil rights, “Which Rights must be violated if Laws, respecting the internal Government, and Taxation of themselves, are imposed upon them by any other Power than that derived from their own Consent, by and with the Approbation of their Sovereign, or his Substitute,” and stating that as a people they had been loyal and zealous in meeting the expenses of defense of America, and that they would be willing to meet their proportion of any necessary expense for the defense of America, “as far as the Circumstances of the People, already distressed with Taxes, would admit of, provided it were left to themselves to raise it, by modes least grievous.”

2. That a memorial be sent to the House of Lords asking them as hereditary guardians of British liberty and property, “not to suffer the People of this Colony to be enslaved or oppressed by Laws respecting their internal Polity, and Taxes imposed on them in a Manner that is unconstitutional.”

3. That a remonstrance be sent to the House of Commons “to assert, with decent Freedom, the Rights and Liberties of the People of this colony as British Subjects; to remonstrate that Laws for their internal Government, or Taxation, ought not to be imposed by any Power but what is delegated to their Representatives, chosen by themselves;” and to suggest that England’s proposed policy might force the Virginians to manufacture the things they now buy from England.

4. That the Committee of Correspondence answer the letter from Massachusetts, assuring that colony that the Virginia Assembly is alive to the danger to the right of self-taxation, “and that the Assembly here will omit no Measure in their Power to prevent such essential Injury from being done to the Rights and Liberties of the People.”

Despite the protests by Virginia and other colonies, the Stamp Act was passed by Parliament on March 22, 1765 to be of effect in the colonies beginning November 1 of that year. News of the Act’s passage reached Virginia in April 1765, but the sparks really didn’t begin flying until May, when a young, newly elected member from the county of Louisa took the ancient oath of office and set out to use all his talents to fight this latest example of British tyranny. That brash young firebrand was, of course, Patrick Henry.

According to the official Journal of the House of Burgesses, Patrick Henry took his seat on May 20, 1765. He had already achieved a modicum of notoriety thanks to his zealous advocacy on the part of Nathaniel Dandridge in the Dandridge-Littlepage contested election and to his participation in the case that came to be known as the Parson’s Cause. There is some question as to how Patrick Henry was able to be elected to the august representative body of the Old Dominion at such a young age (he was 28 at the time), but there is little question as to the impact he had on that group of men from the first days of his term in it.

On May 29, the day of his 29th birthday, Patrick Henry offered five resolutions for consideration by the House of Burgesses. Henry in fact offered the resolutions to the Committee of the Whole House. The House had gone into this Committee of the Whole after a motion to that effect was made by George Johnston, a member from the county of Fairfax, and seconded by Henry himself. Johnston is an important member of the dramatis personae of the drama that surrounds the Stamp Act resolutions. Some time before offering his resolutions to the House, Patrick Henry shared them with both Johnston and John Fleming, a Burgess from Cumberland, both of whom pledged their support to Henry and to the passage of his resolutions.

In consultation with Fleming and Johnston, Henry had decided to offer not five but seven resolutions in response to the Stamp Act. Henry moved for the adoption of the seven resolutions by the Committee of the Whole, the motion was seconded by Johnston, and debate ensued. The debate was heated and illuminated a fracture in the House between conservative Tidewater aristocrats and the more liberal and independent-minded Piedmont and backwoods representatives, of which Patrick Henry was one. Apparently, all seven amendments were finally approved by the committee and recommended to the whole House for final consideration and vote.

These seven resolutions were passed by the Committee of the Whole and sent to the House on May 30. Before any action could be taken by the whole body of the House, however, the seven resolutions were passed on to the colonial newspapers and by July were printed with various alterations as official resolutions of the Virginia House of Burgesses.

May 30 and 31 of 1765 were days of vigorous debate in the House of Burgesses. Although only 39 of the approximately 115 Burgesses were present for the debates and votes, Henry’s proposals polarized the members of the House. The older, more conservative members opposed Henry’s resolutions on the grounds that the action taken the previous year by the House of Burgesses sufficiently responded to the Stamp Act, especially in light of the fact that Parliament had yet to answer those earlier resolutions. Younger members, including Henry, argued that the taxes required under the Act would take effect in a few months and immediate action was necessary. The resolutions were debated vociferously, and on May 30 only the first five of the seven were approved, albeit by small margins, especially the fifth, which apparently passed by the narrowest of margins — a single vote. It was during the debate on this fifth and most contentious of the first five resolutions that Patrick Henry spoke words that have been passed into the lore of the early days of American discontent with English rule.

Patrick Henry rose to speak in support of his fifth resolution. Biographer William Wirt describes his stirring remarks as well as the reaction of offended Burgesses:

It was in the midst of this magnificent debate, while he was descanting on the tyranny of the obnoxious Act, that he exclaimed, in a voice of thunder, and with the look of a god, “Caesar had his Brutus — Charles the first, his Cromwell — and George the third — ” (“Treason,” cried the Speaker — “treason, treason,” echoed from every part of the House. — It was one of those trying moments which is decisive of character. — Henry faltered not an instant; but rising to a loftier attitude, and fixing on the Speaker an eye of the most determined fire, he finished his sentence with the firmest emphasis) “may profit by their example. If this be treason, make the most of it.”

Working on the Wording

Unfortunately, an actual text of Henry’s remarks does not exist — and did not exist for Wirt when he penned the above account in 1817, more than half a century after the speech was given. Yet despite the passage of time, Wirt tried to unearth the elusive truth from the scant evidence available, and his description of the speech has become a calcified part of the lore of colonial America and its great struggle for freedom and independence.

Wirt relied on accounts of the speech provided him by Thomas Jefferson, John Tyler, and Paul Carrington. Two of these, Jefferson and Tyler, purportedly sat outside the door of the House chamber while Henry and the other Burgesses debated the Stamp Act resolutions. The chief problem with all of these recollections is that they all were written many years (approximately 50 years) after the fact. Let’s examine these three briefly:

• First is the account provided by Paul Carrington, who was a contemporary member of the House of Burgesses. However, at the time Henry delivered his Stamp Act speech, Carrington had not taken his seat and therefore was not an eyewitness. Carrington provided the basis of the account of the speech described by Wirt. He informs Wirt that Henry had actually said the words, “if this be treason, make the most of it.” It is significant to remember that Carrington sent this account to Wirt in 1815, long after Henry’s reputation as a fiery patriotic orator had passed beyond the realm of debate.

• The second account is from Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson claimed to have been standing outside the door of the chamber of the House of Burgesses with John Tyler and gave the following account to Wirt: “I well remember the cry of treason, the pause of Mr. Henry at the name of George III, and the presence of mind with which he closed the sentence and baffled the charge vociferated.” This doesn’t exactly correspond with Carrington’s account, although it does not contradict it, either.

• Finally, we consider the account of John Tyler. John Tyler reportedly confirmed to Wirt the version of the story provided by Carrington, including the potent ending. Jefferson, it should be noted, was confirming the account of Tyler provided him by Wirt. It seems, therefore, that Carrington’s version of events is the common ancestor of all these accounts and the source of Wirt’s nearly mythological description of the events.

The three accounts of the event told or sent to Wirt come from men of untainted reputation. Jefferson was the President of the United States and a political enemy of Patrick Henry who would have no motive for adding air to the inflation of Henry’s popular image. Carrington was a lawyer and judge who put great stock in the precision of testimony. Tyler, a future governor of Virginia, benefited from nearly universal respect among his contemporaries. Certainly he had no obvious reason to invent the scenario he reported nor to put words in Patrick Henry’s mouth.

While we may never know for sure what Patrick Henry said, we do know that at the end of the speech, a final, binding vote was taken by the House. As stated above, the first five of the seven resolutions passed, the fifth only barely. By this time, the narrowness of the resolutions’ passage was inconsequential, as their author had already become the voice of American resistance to English despotism.

Content with the passage of his resolutions, Henry left for home, convinced he had accomplished a great work. On May 31, the day after Henry delivered his speech and rode out of Williamsburg, the House reconsidered the resolutions and the fifth and least popular of them was rescinded, leaving only the first four as officially adopted resolutions of the Virginia House of Burgesses. The fifth resolution, the one rescinded by what Jefferson called “the more timid” members of the House, was the one that read:

Resolved, Therefore that the General Assembly of this colony have the only and sole exclusive right and power to lay taxes and impositions upon the inhabitants of this colony and that every attempt to vest such power in any person or persons whatsoever other than the General Assembly aforesaid has a manifest tendency to destroy British as well as American freedom.

Patrick Henry’s fame was beyond rescission, however, and the four resolutions he penned and helped pass were quickly and thoroughly disseminated throughout America. They became the basis for similar responses in the other colonies. Patrick Henry’s gift for oratory had, only 11 days after he took the oath of office for a Burgess, guaranteed his place in the front of the minds of patriots from Massachusetts to Georgia.