Today marks the anniversary of the assassination of President James Abram Garfield in 1881, an act which led directly to the passage of the Pendleton Act of 1883, which created the United States Civil Service System. As historic as the murder of Garfield was, the creation of the Civil Service System has had a far greater impact on the lives of ordinary Americans.

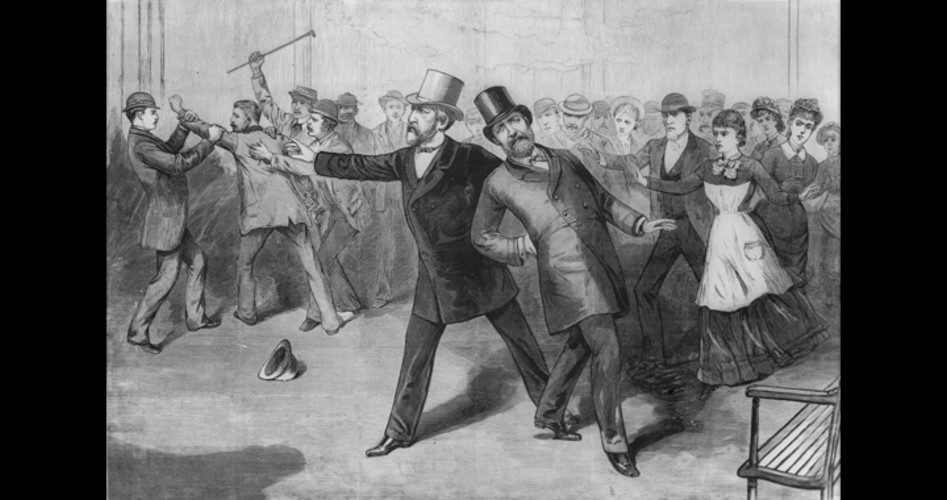

President Garfield was at the railway station in Washington, D.C. (not Union Station, which did not open until 1907), ready to take a brief trip back to his home state of Ohio, when his assassin, Charles Guiteau, shot him from behind. Garfield did not die immediately, but lingered for eleven weeks, during which time multiple doctors worked to find the bullet, which had lodged in his back.

Medical hygiene was not well understood at the time, and Garfield developed an infection that finally killed him. Vice President Chester Alan Arthur succeeded Garfield in the presidency before Garfield died, but could take no action as president as the Constitution did not provide for what to do when a president is still living, but is incapacitated. The situation with Garfield, and the later disabling stroke suffered by President Woodrow Wilson, were both cited during the discussions of the 25th Amendment, which details what to do in a situation of presidential incapacity.

The 25th Amendment would not be adopted until almost a century later, in the aftermath of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. Since Kennedy lived for about half an hour after a bullet had destroyed much of his brain, the specter was raised of what would have been done had Kennedy lived, but in a vegetative state?

Another — more immediate — impact of the Garfield assassination was that it led to the creation of the U.S. Civil Service System. This replaced the so-called “spoils system” in which all employees of the U.S. government were appointed by, and served at the pleasure of, the president of the United States.

Garfield’s assassin, Charles Guiteau, has been written off by most historians as a deranged lone gunman (just like Lee Harvey Oswald, who killed J.F.K., and like most assassins of powerful political personalities), angry that Garfield had not named him ambassador to France. For at least a decade, there had been a push from “reformers” to replace the spoils system with a system in which government employees would be selected not for their political party, but rather on merit.

President Rutherford Hayes, elected in 1876 on the Republican ticket, was an advocate of a merit-based system, but was opposed by the “Stalwart” Republicans, led by Senator Roscoe Conkling, and no bill could pass Congress. Hayes issued an executive order that no employee of the federal government could be forced to make campaign contributions, or even participate in the election process.

At the time, the main source of revenue for the federal government was the tariff — taxes on incoming foreign goods — and this required the employment of many federal workers to collect the tariff. The Port of New York was an important point of entry of foreign goods into the country and the Collector of the Port, Chester Arthur, a protégé of Conkling, refused to obey the president’s order, leading to his eventual dismissal. Congress, however, refused to adopt any civil service system, as Hayes requested.

With the Republicans in control of the Congress, Democrats seized upon civil-service reform as an issue, with Democratic Senator George Pendleton of Ohio introducing a bill to create a civil service system, with merit examinations.

The next president was also a Republican — James Garfield. The Republicans picked Arthur — the man Hayes had fired at the New York Port — as Garfield’s running mate. Arthur became an unlikely advocate of civil service reform after Garfield’s assassination, as advocates used the tragedy to advance the Pendleton Act, which finally passed in 1883, by large margins of 38-5 in the Senate and 155-47 in the House of Representatives. At first, only about 10 percent of federal jobs were covered by the law, but more and more federal employees have fallen under its requirements since its passage.

At first glance it might appear logical that the government should hire its employees based on merit, rather than on politics. After all, what difference does it make whether a letter carrier is a Democrat or a Republican?

But the negatives of the creation of the civil service system are not as well understood. Prior to its passage, voters could throw out the employees of the incumbent party, if the bureaucracy was not responsive. Indeed, the civil service system is largely responsible for the rise of the modern bureaucratic state in which federal workers feel no need to respond to the citizens of the country. On the contrary, they have become the permanent government of the country, with many believing that while presidents come and go, they remain. These faceless and unelected bureaucrats make administrative rules that have the same effect as laws that affect the lives of millions of Americans, whom they often consider themselves the masters of rather than the servants of. They truly comprise the Fourth Branch of the Federal Government, a situation which no doubt would have repulsed the Founding Fathers.

Before the creation of the civil service system, campaign funds came from federal workers, who had a vested interest in their party winning the election, or alternatively, from those in the other party who wanted federal jobs. Today, wealthy donors have replaced these workers. It is difficult to see how this is a better situation.

At the time of the passage of the Pendleton Act, the federal government was quite small, and its powers were much more restricted. Today, with the explosion of areas in which the federal government can meddle in our affairs, an army of federal bureaucrats are needed to put all of these regulations into place.

Perhaps America would have gotten a bloated civil service system anyway. It was perhaps the first of the “progressive causes” that expanded the scope and size of the federal government, although it is not often thought of as part of the Progressive Era itself. But Charles Guiteau’s bullet not only killed a president — it also dealt a death blow to much of citizen control of its own government.

Steve Byas is a college history instructor, and author of History’s Greatest Libels. He may be contacted at [email protected]