Did the Founding Fathers support the idea of government-run healthcare? The question seems to answer itself. The Founders had just thrown off the shackles of big government, putting in its place a limited federal government with explicitly defined powers, none of which involved medical care.

However, some ObamaCare supporters have recently seized upon a heretofore obscure 1798 act of Congress to argue that the men who shaped the Constitution and served in the nascent federal government would indeed have favored some form of universal health insurance. That law, “An Act for the Relief of Sick and Disabled Seamen,” required ships’ captains to garnish a small portion of the wages of their sailors and remit those taxes to the customs collector upon entering a U.S. port. That revenue was then to be used “to provide for the temporary relief and maintenance of sick, or disabled seamen.” The act created the Marine Hospital Fund to operate this network of medical facilities.

Rick Ungar, blogging at Forbes, makes much of this, arguing that it disproves the notion advanced by ObamaCare opponents that the Constitution does not authorize the government to mandate that individuals purchase health insurance:

Keep in mind that the 5th Congress did not really need to struggle over the intentions of the drafters of the Constitutions [sic] in creating this Act as many of its members were the drafters of the Constitution.

And when the Bill came to the desk of President John Adams for signature, I think it’s safe to assume that the man in that chair had a pretty good grasp on what the framers had in mind.

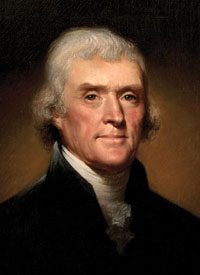

Ungar’s suggestion that there was no disagreement about the Constitution’s meaning among early elected officials is patent nonsense. For example, this same Federalist-controlled Congress passed and Adams signed the egregious Alien and Sedition Acts, which were debated extensively in Congress and vehemently opposed both before and after their passage by Founders such as Thomas Jefferson, Vice President under Adams, and James Madison, the “Father of the Constitution.” Jefferson and Madison went so far as to author secretly the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions declaring that states have the right to nullify federal laws they deem unconstitutional.

The Act for the Relief of Sick and Disabled Seamen seems largely to have escaped the notice of Jefferson and other members of his Democratic-Republican Party, perhaps because they were so preoccupied with fighting the Alien and Sedition Acts. In fact, the Annals of Congress record very little debate about the bill in the House of Representatives and none at all in the Senate. The only objection on constitutional grounds seems to have come from the one Republican who was paying attention, Rep. Joseph Bradley Varnum of Massachusetts, who said that “he could not reconcile it with that clause of [the Constitution] which says ‘that no capitation or other direct tax, shall be laid, unless in proportion to the census or enumeration directed to be taken,’” according to the Annals.

As to Jefferson, Georgetown University history professor Adam Rothman told the Washington Post’s Greg Sargent that “Jefferson … also supported federal marine hospitals, and along with his own Treasury Secretary, Albert Gallatin, took steps to improve them during his presidency.” This gives the impression that the Sage of Monticello actively favored the act. According to a 1956 Journal of Southern History article by William E. Rooney, however, “Although Jefferson was Vice President when the ‘Act for the relief of sick and disabled Seamen’ became law, there is no evidence that he took any part in it, or even presided over the Senate while it was being debated.”

Still, once assuming the presidency Jefferson did extend the marine hospitals’ reach into New Orleans even before the United States had assumed control of the Louisiana Territory. Of course, Jefferson considered the Louisiana Purchase itself to be of dubious constitutionality, so the fact that he did not seek to repeal but rather expanded federal healthcare for sailors does not necessarily imply that it is constitutional either.

Meanwhile, contra Ungar, there was also disagreement about the constitutionality of the act outside of the federal government. Residents of Charleston, South Carolina, later objected to the construction of a Marine Hospital in their city on the basis that it violated state sovereignty. States’ rights advocates viewed the hospital “as an illustration of the Federal government’s abuse of its powers,” the National Park Service explains on its website. The service elaborates:

In Charleston, many people resented the heavy hand of the Federal government in the construction of their Marine Hospital, which began in 1831. Even though [hospital architect Robert] Mills had left the city only two years earlier, state’s rights supporters were particularly infuriated by the replacement of their local architect and contractors with Mills and other professionals from Washington D.C., as well as the increased costs of the project. By the time of its completion in 1834, the Marine Hospital was rejected by Charlestonians as an unworthy civic accomplishment.

Thus, while some members of the political elite may have believed in the constitutionality of the Marine Hospitals, plenty of average Americans did not. Nor is it surprising that costs skyrocketed; it was a government project, after all.

The reasoning behind the law was remarkably similar to the one put forth for ObamaCare, according to a Common-place.org article on the Marine Hospitals by Gautham Rao. First was the economic rationale: A healthy workforce is a productive workforce. Politicians being ever under the sway of whatever theory can be used to justify an increase in their powers, many in Washington believed in the mercantilist proposition that the nation that rules the most overseas markets rules the world, in turn making its government — and perhaps its citizens — rich. And the best way to rule the seas and their ports was, they thought, to have a healthy maritime workforce, enforced by government fiat. How different is that from today’s sales pitch that forcing everyone to have health insurance will reduce healthcare costs and therefore make us all wealthier?

Second, as with ObamaCare and most other government programs, a large dose of paternalism played into the passage of the act. Rao writes:

In Anglo-American society, mariners were partially free and partially unfree laborers. It was believed that the mariner had volition enough to choose his course and negotiate for wages. But it was also believed that the mariner lacked sufficient sense to care for his own wellbeing. From this sentiment arose the infamous stereotype of “Jack Tar” as a coarse, hard-drinking character who purposefully exposed his own body to great harm. If Jack Tar failed to care for himself and if commerce and society so depended on Jack Tar, was it not society’s responsibility — and was it not in society’s best interest — to preserve and protect the mariner for his own good and for the public good? As Maine Senator F. O. J. Smith put it in 1838, “both the Government and the merchant” had “almost the same abiding interest with the sailor himself, in a matter upon which so much depends for a requisite supply of healthy and able-bodied seamen.”

Again, so the argument goes, since Americans today cannot be trusted to make their own decisions regarding health insurance — whether it comes to accepting a job that does not provide it or choosing not to buy it on an individual basis — the government, “in society’s best interest,” must force them to buy it.

So, yes, some of the less liberty-minded Founders did, unfortunately, believe in government-run healthcare for sailors. Others who were more concerned with liberty, such as Jefferson, failed to object to the proposition when it was being debated and ended up endorsing it by their later actions. This does not, however, imply that such a system is either constitutional or wise. One would not, after all, recommend owning slaves simply because Jefferson did so; to do so is both (now) unconstitutional and unwise (not to mention inhuman). Nor does it imply that the same men who at one time or another favored the Act for the Relief of Sick and Disabled Seamen would have supported a federal health-insurance scheme for every American. They clearly intended for their law — slightly over one page long, as compared to the 1,000-plus pages of ObamaCare’s two acts — to have a very limited scope.

At the same time, this early attempt at socialized medicine in America can serve as a cautionary tale. The Cato Institute’s Chris Edwards writes that the Marine Hospital Fund was “plagued by cost overruns, administrative mismanagement, and rationing of care” from its inception. Did this failure of socialized medicine lead to the repeal of the act that created it? Of course not! Rao explains:

The marine hospitals grew rapidly in the early republic. A system that included twenty-six facilities in 1818 expanded to include ninety-five by 1858. Much of this expansion owed to the efforts of Dr. Daniel Drake, perhaps the United States’ most famous physician of the antebellum era. Drake, echoing Alexander Hamilton in the Federalist, believed that “the commerce of the West,” must serve as “a nursery of seamen” for the nation. The seemingly transcendent American desire for equal regional distribution of pork and patronage was also important. The “old Atlantic States” already had federal marine hospitals, so why did the newest states deserve any less? According to Drake, “justice requires that the advantages they would afford should be reciprocally enjoyed.” By 1860, new marine hospitals were to be found in western ports, such as Napoleon, Ark., Evansville, Ind., and San Francisco; on the hubs of the Great Lakes, such as Cleveland, Chicago, and Galena, Ill.; and even in some aging eastern ports, such as Burlington, Vt., Portland, Me., and Ocracoke, N.C. Annual hospital admissions, which ranged in the low hundreds throughout the first decade of the nineteenth century, consistently exceeded ten thousand during the 1850s.

The lure of “free” healthcare extended to those along major rivers such that, according to Rao, “cities such as Paducah, Kentucky, demanded only a ‘NATIONAL HOSPITAL, with national funds, and administered by national functionaries.’”

Even after “scandals regarding mismanagement at the Marine Hospital Fund,” avers Edwards, the system was not put to rest. Congress merely restructured the system as the Marine Health Service and put the Supervising Surgeon (now Surgeon General) in charge of it. “Over the years,” Edwards says, “the MHS expand[ed] its activities far beyond the original limited focus on aid to seaman [sic].” The MHS was given authority over quarantines and other health crises, which ultimately led to the U.S. Public Health Service Commissioned Corps. It opened a disease research laboratory that evolved into the National Institutes of Health. And the MHS itself became today’s Public Health Service.

The originally limited project of providing healthcare to sailors still exists 213 years later, long after shipping ceased to be the engine of American commerce, and is now a bureaucratic behemoth. Imagine how humongous the ObamaCare bureaucracy, already impossibly huge, is likely to become in decades hence.

This is the universal experience with government programs. The Founders — from Jefferson to Adams and everyone in between — should have seen it coming and should have been wise enough to oppose it both on principle and on grounds of constitutionality. Unfortunately, they, like all of us, were imperfect humans, and today we must live with the consequences of their long ago capitulation to phony economic theories, nanny-state paternalism, and plain old political patronage — not to mention the smug preening of leftists who, in an effort to revive flagging public support for a clearly unconstitutional takeover of the healthcare system, claim the Founders’ mantle of liberty as their own.

Graphic: Thomas Jefferson