May 1917 was a time of troubles. In France the titanic Battle of Arras was raging. The United States, which had declared war on Germany the previous month, was in the process of drafting millions of men, more than 100,000 of whom would lose their lives. The great empire of Russia was in turmoil, its Czar, Nicholas II having abdicated the throne in February in response to the first of two revolutions. The second revolution — the October bloodbath that would thrust those living under Russian rule under the heel of Bolshevism — lay only months away.

The tiny nation of Portugal, geographically remote from the horrors of world war, was not spared the ravages of that turbulent period. Many thousands of her soldiers were in the battlefields of France fighting alongside Britain and her allies; more than 7,000 would not return to their native land. At home, Portuguese politics had been in turmoil since 1910, when a lesser-known October Revolution overthrew King Manuel II and established a secular, anti-Catholic republic inspired by the French revolutionary regime. The so-called First Republic that lasted until 1926 was a time of unending political and civil strife, with the unfortunate Portuguese enduring the chaos of 8 presidents and 38 prime ministers against the backdrop of a revolutionary populism with the Jacobin-inspired goal of eradicating traditional Portuguese culture and religion root and branch.

Yet Portugal in the early 20th century was, as she had been since the loss of her greatest colony, Brazil, in the 1820s, at the periphery of world affairs. The nation of explorers that had risen to world prominence in the age of Balboa and Da Gama had fallen far behind the Dutch, English, French, and other European powers in the scramble for colonial prestige, and her internal broils in 1917 were of little concern to anyone beyond her own borders.

All of that was soon to change, however, and not because of any great Portuguese revolution in human affairs. On a peaceful spring morning, May 13, 1917, three children from the village of Aljustrel, a tiny jumble of whitewashed houses and pastures not far from the town of Fatima, were playing on a pastured hillside known as the Cova da Iria, building a make-believe house out of stones.

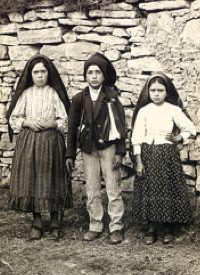

It was the afternoon of the Sunday before the Feast of Ascension, and the three children — Lucia Santos and her younger cousins Francisco and Jacinta Marto — had just attended Mass and enjoyed a picnic lunch. Lucia, a rather plain-looking ten year-old, and her two cousins came from typically pious, hard-working, hardscrabble rural Portuguese backgrounds. Their lives and their Catholic faith were closely intertwined, as had been the case for countless generations of Portuguese farmers before them. It is unlikely that they had been much affected by the revolutionary, anti-religious posture of the government in Lisbon; in those days, the militant secularism that has become the signature characteristic of our age was mostly an urban phenomenon, both in Portugal and elsewhere. Life in Aljustrel and Fatima in 1917 was little different than it had been a century, or two centuries, earlier.

According to the children’s later report, their play was interrupted by a flash of brilliant light. Looking up at the branches of a holm oak tree, they saw a beautiful lady dressed in radiant garments standing above them. She told them not to be afraid, and informed them that she had come from heaven. Lucia, the boldest of the three, asked the lady what she wanted. Their visitor told them that they should return to that same spot at the same time on the thirteenth day of each of the next six months, whereupon the lady would tell them who she was and would reveal to them what she wanted. She instructed them in the meantime to perform their religious duties with exactness, including saying Rosary every day “to bring peace to the world and an end to the war.” Then the transcendent visitor departed, leaving the children astonished.

It did not take long for word of the miraculous visitation to spread around the parish of Fatima. Perhaps not surprisingly for an incredulous age, the children’s report was received with skepticism and even derision, even from family members and from their priest, Father Ferreira. It was Lucia’s mother who took her to Father Ferreira and ordered her to confess to having lied about the event — which Lucia refused to do.

In spite of widespread ridicule and even an offer of money not to keep their next appointment with the lady, the three children were in the Cova da Iria at the appointed time on the 13th of June. The pasture was thronged with local curiosity seekers, but Lucia and her two cousins were undeterred. At the appointed time, the lady appeared, and although none of the onlookers saw the heavenly apparition, all of them heard a strange buzzing sound like a voice whose words they could not understand.

The three children, however, claimed they had been treated to another face-to-face encounter with the lady, and that she had promised that all three of them would go to heaven — Jacinta and Francisco soon, and Lucia later on. She again instructed them to attend to their devotional activities, and also to learn to read and write. When she departed, the children saw vivid flashes of lightning, and even the onlookers saw a small cloud rise up from the tree and the topmost branches bend toward the east, where the lady had disappeared.

“She has gone back to heaven,” Lucia declared to the crowd, “and the doors are shut.”

The days that immediately followed were very difficult for the three children, and especially for Lucia. While certain people, like Ti Marto, the father of Jacinta and Francisco, were supportive and regarded their visions as signs from heaven, many more dismissed the events as children’s imaginings. Father Ferreira went further; in interviews with Lucia, he suggested that the visions, though real, were not from God at all but from the devil. Although Lucia maintained the truth of her story, she began to doubt the sanctity of her visions and of the heavenly lady.

Tenor of the Times

Such misgivings were understandable, given the tenor of the times. Historically Roman Catholicism and the Orthodox churches of the east all have rich traditions of miracles, many of which have been associated with critical historical events. It was the appearance of a shining cross in the heavens before the Battle of Milvian Bridge that led to the conversion of the Emperor Constantine. The remarkable military campaigns of Joan of Arc were preceded by a series of (to the secular-minded) unexplainable visions vouchsafed to an obscure teenage girl. Extraordinary natural events, like the appearance of a comet or a severe earthquake, were routinely interpreted as signs of the times, tokens of divine displeasure or harbingers of coming disasters like war or the death of a monarch.

Rightly have the early centuries of Western Civilization been characterized as an “Age of Faith;” all great cultures are born and propelled to preeminence by transcendent conviction, as Spengler, among many others, has observed. The germ of culture is always and everywhere the cultus, the set of assumptions about transcendence that enables men to fix their beliefs and motives on something higher than mere mortal transience. One need read no further than the Pentateuch, Herodotus, or Livy, to perceive that the ancient Hebrews, Greeks, and Romans were no less convinced of the reality of the transcendent and the Absolute — and of its role in the affairs of men — than were the schoolmen, popes, and princes of the Middle Ages, or even, in a more latter time, the American Founding generation.

But Western Civilization, at least in the Old World which had birthed it, had become cheapened and thoroughly secularized by the early twentieth century. In place of religion radical, Utopian politics had become the altar where the leaders, the elites, and the visionaries worshipped. The desire to rid the Old World of oppressive monarchy that had originated with the French Revolution had turned into an all-out campaign against tradition, against restraint, against aesthetics, and above all, against religion. In the arts and humanities, the ugly, discordant, and secular had almost entirely replaced the lovely, the harmonious, and the inspiring as norms to be upheld. The music of Bach and Mendelssohn, the painting of Velázquez and Rembrandt, the literature of Jonson and Tennyson — all had become relics of a culture and worldview that no longer resonated.

A good case could be made for the argument that the secularization and decline of Western culture began in Portugal. In 1755, the city of Lisbon – one of Europe’s most opulent sea ports — was utterly destroyed by the worst natural disaster (aside from sickness) to strike Europe in modern times. On the morning of November 1, 1755 — All Saints Day — a tremendous earthquake, probably measuring well over 8.0 on the modern Richter scale, destroyed much of the city, killing tens of thousands of people. The entire glorious esplanade that ran along Lisbon’s magnificent harbor, along with uncounted souls who happened to be strolling on it, was swallowed up in the earth. A short time later, an immense tsunami swept away much of what was left of the lower city, and a huge conflagration consumed much of what remained. Very little of the city — either of living human beings or of buildings — was left standing at the end of that terrible day, and the whole of Europe marveled. Here was a catastrophe of Biblical proportions, yet with no apparent motive or purpose. Portugal was regarded at the time as an exemplar of Catholic piety, and her rulers among the Catholic Church’s leading patrons. Yet in the great earthquake, saints and sinners alike had been swept away, crushed, buried alive, and burned to death without discrimination, and many enquiring minds wanted to know why.

Among these were men like Rousseau and Voltaire, whose radical ideas would prepare the way for the French Revolution a generation later. Voltaire in particular was shaken by the event, concluding that the earthquake was evidence that God either did not exist, or was not concerned with the affairs of men. In his famous and influential work Candide, Voltaire cited the earthquake as evidence that we do not, in fact, live in a world supervised by a benevolent deity. More than any single event, the Lisbon cataclysm triggered a revolution in the Western worldview, as betokened a generation later by the French Revolution and by its offspring, the various militant socialist movements of the 19th and 20th centuries.

By the time of the First World War, there was little inclination in Europe to believe that God had any hand in the affairs of men. There was only the State, and what men chose to make of it and themselves. The apocalyptic slaughter on the battlefields of France, Turkey, Russia, and elsewhere, not to mention the meteoric rise of Communism in Russia, did little to contradict this notion. Men really were soulless animals, there was no healing balm for man’s tragic condition except his own ingenuity, and the heavens — if they existed at all — were shut.

Occurrences of Fatima

And then came the occurrences of Fatima, which would have seemed more natural a half-millennium earlier. Lucia, Jacinta, and Francisco likely had no notion of the great historical trends that had taken Christendom hostage, but they were perplexed and hurt when, even in comparatively pious rural Portugal, their visions were met with incredulity and scorn.

So great became Lucia’s doubts concerning the divinity of the lady of her visions that she nearly decided not to keep the July 13th appointment. On the evening of July 12th, she told Jacinta that she did not intend to go to the Cova da Iria the next day. Jacinta begged her to reconsider, telling her that the lady would surely come and would miss Lucia. Lucia replied that she had no doubt the lady would be there, but that she was afraid the lady was of the devil, not God. But the next morning, she awoke with all doubts dissipated, and accompanied the other two children to the Cova da Iria.

By this time, the fame of what was happening had spread through the Serra da Aire — the mountains of central Portugal — and was beginning to reach as far as the outer world. The Cova was full of curiosity seekers both faithful and faithless; one chronicler likened the event to a bullfight. The three children had to be escorted through a crushing press of onlookers to the base of the now-famous oak tree. Scarcely had they arrived when Lucia announced to the crowd that the Lady was coming.

A hush fell over the sea of spectators. As before, witnesses saw a small cloud alight in the upper branches of the tree and heard again the strange buzzing sound. Some saw a small globe of light. But only Lucia and her two cousins saw the glorious vision that followed, the most significant that they had yet seen. As they later testified, the lady enjoined them once again to attend to their religious duties, and, at Lucia’s petition, promised to perform miracles of healing on behalf of certain people. She also promised, if they came every month at the appointed time, to perform a miracle in October to show the world the truth of the visions.

Then the lady spoke to Lucia of the world and of things to come. “If you do what I tell you,” she said, “many souls will be saved, and there will be peace. This war will end, but if men do not refrain from offending God, another and more terrible war will begin.” The lady then commanded Lucia to instruct the church to pray on Russia’s behalf. “If my wishes are fulfilled,” she told Lucia, “Russia will be converted and there will be peace; if not, then Russia will spread her errors throughout the world, bringing new wars and persecution of the Church; the good will be martyred and the Holy Father will have much to suffer; certain nations will be annihilated.” The lady predicted that, in the end, faith would triumph over error, and departed. The throng of onlookers heard a tremendous thunderclap and felt the earth tremble.

This third apparition on July 13 is among the most significant of the events at Fatima, because it confirmed that the visions of young Lucia and her two cousins were no mere local miracles; they were intended for worldwide consumption. It is especially remarkable, at least for would-be skeptics, that a humble and uneducated peasant girl would emerge from the third apparition with a perspective on what was then simply called the world war and on the need for special prayers for Russia, a word she had never previously heard. This occurred prior to the Bolshevik revolution in Russia that was to prove one of the signature events of the 20th century. The third apparition included the lady’s announcement that she would come with a specific request regarding Russia.

(Lucia eventually left home and entered religious life where, she reported, she continued to receive visits from the lady she had first encountered at Fatima. In 1929 while living the life of a nun at a convent in Tuy, Spain, Lucia said she received the lady’s specific request that the Pope, along with the world’s bishops, consecrate Russia on a single day, an injunction that, despite the ecclesiastical recognition given to the Fatima events and Lucia’s transmission of the message to several popes, has never been carried out.)

There was no visitation on the 13th of August. Lucia and her two cousins found themselves unable to keep their appointment with the lady, because the mayor had kidnapped them and held them as prisoners in his own house, threatening to have them thrown into boiling oil if they did not confess their deception. The crowds at Cova da Iria heard thunder and saw the cloud atop the oak tree, as before, and some witnesses recorded other prodigies besides, like brilliant rainbow-hued light — but neither the lady nor her three young devotees made an appearance. The following day, the mayor — a professed atheist — threw the three children in jail with hardened criminals. Later that day, in an effort to terrorize the children into confessing, the mayor had them taken away one by one — to be boiled alive, he told them. Though the three children believed they were to be martyrs, they neither recanted nor told the secrets that the lady had revealed to them. Finally, conceding to popular sentiment, the mayor released the three children.

A few days later, the three children claimed to have seen the lady again, albeit at a different spot. She assured them that she would continue to make her appearances and would manifest a special miracle on October 13. On September 13, however, they kept their appointment at the Cova da Iria, along with an immense crowd of onlookers, many from far-flung places who had come to ask boons of the lady on behalf of themselves or afflicted loved ones. For the fifth time the lady spoke with Lucia and her two cousins. Again there were prodigies in the heavens, including, according to some witnesses, a peculiar paling of the sky that allowed the stars to become visible at mid-day.

By the arrival of October 13, the day when the lady had promised to show a public miracle as confirmation of the children’s vision, the event had been publicized throughout Portugal and beyond. Despite the sneering skepticism of the big city newspapers reporting on the Fatima phenomenon, the entire country was entranced by the story and by the possibility that, in the midst of these worst of times, for Portugal and for the entire world, Divine Providence was actually taking a hand in the affairs of men. From every corner of Portugal tens of thousands of pilgrims gathered at Fatima in anticipation of the great event, traveling barefoot, by oxcart, or by automobile. Jaded urban journalists and cynical intellectuals mingled with simple, believing peasants. Although the true figure will never be known for certain, as many as 100,000 people were crowded into the Cova da Iria by midday on October 13, 1917.

On that day, Italy was weeks away from total defeat at the hands of Austria-Hungary, while Russia was about to fall under the totalitarian rule of Vladimir Lenin in the infamous October Revolution. And in Fatima, Portugal, where what so many had come to believe was the light from heaven had recently shone, rain was falling.

In spite of the crowds, the rain, and the mud, Lucia, Jacinta, and Francisco made their way to the foot of the holm oak tree and waited. Before long, the lady appeared for what was to be the last time. She identified herself to the children as the Lady of the Rosary, promised that the war would soon end and the soldiers return home, and requested that a chapel be built at the Cova da Iria. As a last gesture, she performed the long-promised miracle.

The three children saw the clouds suddenly break up and their benefactress ascend to heaven beside the suddenly dazzling sun. There then appeared, as they later recorded, successive visions of the Christ Child and his earthly father, St. Joseph, before the vision dissipated.

This time, the assembled multitudes saw a prodigy none would ever forget, one that was confirmed by the recorded testimony of hundreds of witnesses. According to some, Lucia called out, “Look at the sun!” prompting thousands of eyes to turn heavenwards. The clouds suddenly were swept away, and the uncovered sun began revolving like a wheel of fire and emitting rays of every color. As the once-cynical Lisbon daily, O Dia, reported a few days later:

At one o’clock in the afternoon, midday by the sun, the rain stopped. The sky, pearly grey in colour, illuminated the vast arid landscape with a strange light. The sun had a transparent gauzy veil so that the eyes could easily be fixed upon it. The grey mother-of-pearl tone turned into a sheet of silver which broke up as the clouds were torn apart and the silver sun, enveloped in the same gauzy grey light, was seen to whirl and turn in the circle of broken clouds. A cry went up from every mouth and people fell on their knees on the muddy ground….

The light turned a beautiful blue, as if it had come through the stained-glass windows of a cathedral, and spread itself over the people who knelt with outstretched hands. The blue faded slowly, and then the light seemed to pass through yellow glass. Yellow stains fell against white handkerchiefs, against the dark skirts of the women. They were repeated on the trees, on the stones and on the serra. People wept and prayed with uncovered heads, in the presence of a miracle they had awaited. The seconds seemed like hours, so vivid were they.

According to another influential paper, O Século, the sun appeared to some to dance in the heavens. More extraordinarily still, what is now known as the “Miracle of the Sun” was observed by many not even present at Cova da Iria that day, some more than twenty miles distant. Not only did the tens of thousands witness the extraordinary activity of the sun, all of those soaked-to-the-skin people suddenly found themselves and their clothes completely dry.

Fatima Today

Fatima, Portugal, like Lourdes in France, is today a popular destination for faithful pilgrims and curious tourists alike. A magnificent basilica erected in honor of the Virgin Mary after the events of 1917 plays host to millions of pilgrims every year, especially on May 13 and October 13. For millions of faithful Catholics around the world, the appearances of the Virgin Mary to three small children were among the greatest miracles in history, a sorely needed balm for a troubled world. For the world at large, the war did soon end, as the lady of Fatima had promised and, in a latter generation, even the Russian bear seems to have been placated. For long-suffering Portugal, the miracles at Fatima perhaps prefigured the end to a time of troubles. After the shocking assassination of popular president Sidónio Pais in 1918, the First Republic ran aground, dissolving into partisan strife until 1926, when António de Oliveira Salazar set up the conservative Estado Novo (“New State”) that ended Portugal’s 16-year secularist experiment.

As for the three children of Fatima, Francisco and Jacinta both perished in 1919 in the Spanish flu, leaving only Lucia to live a lifetime of piety as a witness of the events. She became a nun and reported other miraculous visions throughout a long life. Fatima itself stands witness to the enduring character of the sacred and the miraculous, a reminder of things unseen and uncomprehended that occasionally inject themselves into mortal affairs. It is testimony that civilization, however much mortal men seek to profane it, is, after all, a product not of the temporal but of the divine.

The lady’s request regarding the special consecration of Russia, mentioned to the children in July 1913, and given in complete form to Lucia in 1929, has yet to be honored. Not only faithful Catholics but men of other faiths have petitioned the pope to do as he has been asked by Lucia following the lady’s instructions. As these students of the Fatima revelations and the requests that followed have repeatedly noted, it would require little effort and no expense for the pope to tell the world’s bishops to join with him in their own houses of worship on the same day to state the special prayers from the lady transmitted by Lucia. One after another, these men who have studied the events that started at Fatima repeatedly ask, “Why hasn’t it been done?” And that is a question this author cannot answer.

Photo: The three Fatima children — Lucia, Francisco, and Jacinta