It was the end of 1782 and the War for Independence was all but over, but the details of the official peace treaty had not yet been hammered out between the American delegation (John Jay, Benjamin Franklin, and John Adams) and their British counterpart (David Hartley). The peace was uneasy, however, as British troops remained stationed in New York and various western outposts and American troops were ordered not to stand down until the British abandoned their posts. The lack of wartime duties gave way to boredom among the soldiers, fresh from victory over a tyrant.

In this atmosphere, the plan for a coup d’état developed, a plot known to history as the Newburgh Conspiracy.

Named for the town in New York where the Continental Army was camped, the Newburgh Conspiracy was not the first attempted revolt of soldiers experienced by the American military. There were insurrections in Connecticut in 1780 and in New Jersey and Pennsylvania in 1781. However, the Newburgh Conspiracy was the first mutiny headed by a cabal of officers. This mutiny was fomented by congressional inability to raise money from the states for the payment of the army’s payroll.

The army was further provoked to anger by proposals in several state legislatures to disband the Continental Army and, by implication, discharge themselves of the burden of making good on promises of payment of a salary to the soldiers and of a half-pay lifetime pension and reenlistment bonuses made in 1780 by Congress.

The expediency of war spurred a reluctant Congress to make these promises, but it was unwilling and constitutionally unable to keep them in the peace that followed the war.

Incredibly, debtor’s prisons awaited retiring officers because of their magnanimous sacrifice of personal financial management during the War for Independence and the systematic and repeated breaking of illusory promises of back pay on the part of state and national legislatures. Washington wisely feared that an exasperated corps of officers might vacate the position they had traditionally occupied between mutinous soldiers and the civil government and that the result would be a bloody civil war.

Washington’s comprehensive knowledge of the histories of the ancient republics of Athens and Rome taught him that the inevitable result of such a violent revolt would be a disdainful tyranny of armed despots that would not be removed but through the shedding of much blood. Such a prospect led Washington to send an envoy of officers to try to persuade friends of liberty in that body that the situation was dire and immediate action was necessary.

There was a cadre of designing officers, however, jealous of Washington’s popularity and growing power, that would not be dissuaded from their malicious intent, despite Washington’s efforts and their own failure to recruit key members of the commanding general’s staff to join their conspiracy.

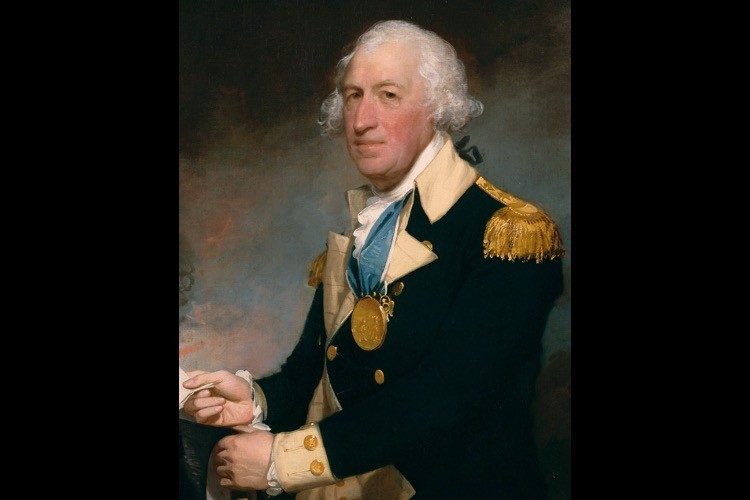

General Horatio Gates, infamous for his dislike of George Washington, was the leader of the conspiracy. He meticulously drew up plans to remove Washington from his post and march on Congress, replacing it with a military leadership, with Gates at its head. To ensure the success of this coup, Gates contacted sympathetic civilians to persuade them to aid in the execution of his traitorous design.

Alexander Hamilton was one of the influential men contacted by Gates, and this proved ultimately to be the plot’s undoing.

Hamilton, a former aide de camp to Washington, was unfailingly devoted to his former commander and he immediately informed Washington of the plot that was being shopped around Philadelphia by Gates and his civilian (read: congressional) confederates.

Upon receipt of Hamilton’s letter (and other letters from friends in Congress), General Washington initiated his own internal investigation of the matter, and what he discovered was a plot deeper, broader, and more nefarious than he ever suspected.

On March 10, 1783, an anonymous notice calling officers to a meeting to discuss the present predicament was distributed among the corps of officers at Newburgh. Gates, who undoubtedly either wrote or dictated the note, was informed by several civilian fellow travelers that the wheels of revolution were now in motion and that the time for action was imminent. The body of the notice promised justice and even went so far as to imply that Washington backed, albeit tacitly, the rumored plans devised to exact this justice. The letter’s message was not subtle:

If you have sense enough to discover and spirit to oppose tyranny, whatever garb it may assume, awake to your situation. If the present moment be lost, your threats hereafter will be as empty as your entreaties now. Appeal from the justice to the fears of government, and suspect the man who would advise to longer forbearance.

Washington’s horror that such a scheme was gaining adherents within and without the ranks of the armed services motivated him to act with amazing dispatch. First, he employed his friend General Henry Knox and other allies within the army to keep him apprised of any further movements toward revolt inside the corps of officers.

Second, he communicated his desire that the meeting be postponed for five days. This tactic was designed to afford him time sufficient to draft a communique to the body of officers.

Finally, Washington occupied himself in the intervening days with drafting and perfecting an address to his army.

To Washington, this speech was critically important and would be the means of diffusing the proposed attack on Congress. The revised date proposed by Washington for delivery of this momentous discourse was the 15th of March, known in the ancient Roman calendar as the Ides of March.

This date was likely chosen purposely by Washington because of its historic significance, a significance that would be understood by anyone with even a casual knowledge of the history of ancient Rome and the assassination of Julius Caesar masterminded by one of his former friends that occurred on that now-auspicious date some 1,800 years earlier.

Under the direction of General Gates, the meeting began. The venue was a small structure called the Public Building and it was filled to capacity. As Gates rose to speak to the assembly of officers, Washington quietly entered through a side door and requested permission to address his men.

Stunned by the attendance of his hated superior, Gates grudgingly acquiesced and ceded the floor to General Washington.

The crowd was hostile, impatient, and prepared to reject any unsatisfactory remedy, even one from Washington himself, particularly if he advocated any further sacrifice or delay in accomplishing the goal of getting recompense from the country they had recently liberated at the cost of so much blood and fortune.

Washington began boldly, chastising the officers for violating military “propriety,” including the anonymity (cowardice) of the organizers of this meeting. Washington continued by reminding his men of the code of honor by which a military man must live and how many among their ranks violated that code in a most vulgar manner.

Major Samuel Shaw reports that at about this point in the delivery, General Washington reached into his pocket, retrieved his recently purchased spectacles, and offered this now-famous apology:

Gentlemen, you will permit me to put on my spectacles for I have grown not only gray, but almost blind in my country’s service.

The point of this message plunged deeply into the hearts of the misled and misguided patriots in attendance, and tears flowed freely.

There before them stood their bespectacled and still beloved commander. He had suffered right along side them, and like Cato, the renowned Roman hero so much admired by American republicans, he refused to sacrifice virtue and propriety on the altar of personal attainment. The same could not be said of Gates and the other co-conspirators, willing to wring power from the pain and frustration of the soldiers.

Upon finishing his remarks, Washington exited hastily, and in his wake all the flames of sedition were doused and resolutions were offered to reaffirm the congregation’s dedication to the cause of a united America and its constitutional republican government.

Here, as in countless other moments of equal gravity, the “indispensable man” once again proved his inestimable worth to the cause of American freedom. He, as all other soldiers, had suffered personal deprivations and debilitations, but he understood that the American cause was more than the cause of George Washington, Horatio Gates, or any individual man or army. This, their common cause, was the cause of liberty.