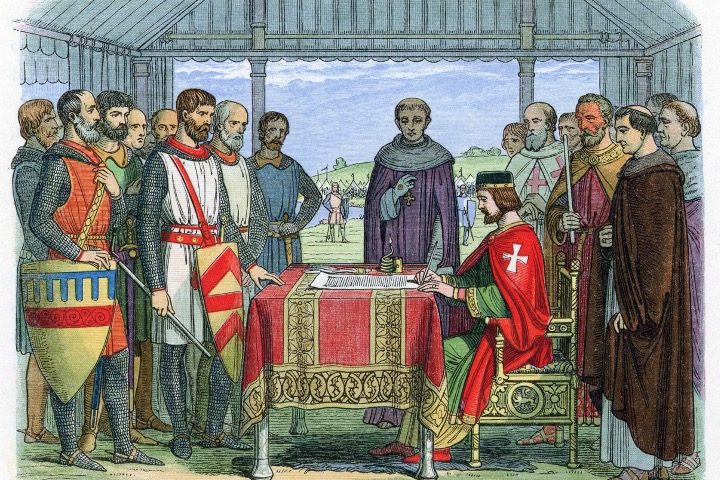

June 15 marks a pivotal date in the annals of liberty: the anniversary of the Magna Carta’s signing at Runnymede, England. Over 800 years ago, this “Great Charter” enshrined liberties so essential that the noblemen who drafted it placed them beyond the reach of the king. They created a document that would lay the foundation for the rule of law, a principle that would echo through the centuries and across the Atlantic to shape the birth of a new nation.

The Magna Carta, signed in 1215, was not merely a treaty between a king and his barons; it was a revolutionary document that declared certain rights as inviolable. It established that the king was subject to the law, not above it, and set forth a series of liberties that would inspire future generations. These liberties were so fundamental that the drafters ensured they were protected from the whims of the monarch.

Fast-forward to America in the 18th century, where the Colonists’ quest for liberty was deeply influenced by the principles enshrined in the Magna Carta. Facing the oppressive policies of King George III, the American Colonists looked back to this historic document as a justification for their vehement opposition. Thomas Jefferson, in drafting the Declaration of Independence, used the Magna Carta as source material for his “long train of abuses and usurpations,” a list of grievances against the British Crown. Jefferson’s words echoed the sentiments of those noblemen from centuries earlier, emphasizing that certain rights were beyond the reach of any king.

John Adams, another Founding Father, claimed that King George III had violated the Magna Carta “thirty times.” This assertion underscored the Colonists’ belief that their rights, as Englishmen, were being systematically trampled upon. They saw themselves as the heirs to the liberties guaranteed by the Magna Carta, and were determined to defend these rights against tyranny.

A decade before the Declaration of Independence was delivered to an outraged King George III, the ill-fated but eminent lawyer James Otis delivered a famous speech challenging the general writs being issued by the king’s father. Otis argued that these writs violated the rights of American-born Englishmen in Boston, and pointed to the Magna Carta as a source of the rights enjoyed by Americans as descendants of those whose liberty was protected from tyranny.

Otis specifically invoked paragraphs 12 and 63 of the Magna Carta of 1215. Paragraph 12 forbids the king from levying any tax on the people without their “common counsel,” a provision that would be reworked into the most famous phrase of the American rebellion: “No taxation without representation.” This principle became a rallying cry for the Colonists, who felt that their rights were being ignored by a distant monarch.

Paragraph 63, the final paragraph of the Magna Carta, declares that all Englishmen “have and hold all the aforesaid liberties, rights, and concessions, well and peaceably, freely and quietly, fully and wholly, for themselves and their heirs, of us and our heirs, in all respects and in all places forever, as is aforesaid.” Americans considered themselves to be the heirs of those alive in 1215. They believed that the 560 years between the signing of the Magna Carta and their own time fell well within the “forever” timeframe for the enjoyment of these liberties. They also believed that the British Colonies in America were included in the “all places” clause of Paragraph 63.

Simply put, Americans believed that they were being routinely deprived of rights that they and their ancestors had been taught for centuries had no expiration date. Furthermore, the Magna Carta expressly granted Englishmen put in such a position by a tyrant the authority to consider any such acts to be “void and null,” as set out in Paragraph 61. This gave the Colonists a legal and moral basis to resist British tyranny and seek independence.

As historian Simon Schama explained in his BBC television documentary series A History of Britain, Englishmen did not consider the Magna Carta as the “birth certificate of liberty,” but rather as the “death certificate of despotism.” This was a view shared by the generation of Englishmen that would become the American Founding Fathers. They saw the Magna Carta not just as a historical document, but as a living testament to the enduring principles of freedom and justice.

While admittedly the concessions obtained from King John by the barons in 1215 had more to do with their baronial privilege than with the rights of common Englishmen, the principle upon which these prerogatives were established was of immeasurable importance. This principle is known as the rule of law. The rule of law basically requires that both the governors and the governed are bound by the same dictates of natural law, that all men are created equal, and that not even a king can place himself above the ultimate sovereign — God, who is the source of all truth and gave unto men their agency.

The rule of law was a radical concept in the 13th century, and it remains a cornerstone of modern self-governing societies. It asserts that everyone, regardless of position or power, is subject to the same laws. This idea was revolutionary at a time when kings ruled by divine right and often considered themselves above the law. The Magna Carta challenged this notion and laid the groundwork for the development of constitutional government.

In 2015, 800 years after the June 15, 1215 signing of the Magna Carta, celebrations were held on both sides of the pond to commemorate this seminal document in the dossier of liberty. These celebrations honored the enduring legacy of the Magna Carta and its influence on the development of principles of popular sovereignty around the world.

More important than spectacles and speeches, however, would be a rededication by modern Americans to pledge our “lives, fortunes, and sacred honor” to the restoration of the rule of law as the guiding principle in the Republic whose liberty our Founders sacrificed so much to secure. In a time when the rule of law is often under threat, it is crucial to remember the lessons of the Magna Carta and to uphold the principles it enshrined.

As we reflect on the significance of the Magna Carta, let us renew our commitment to the values of liberty, justice, and equality under the law that it represents. Let us honor the sacrifices of those who fought for these principles by striving to ensure that they continue to guide our nation. The Magna Carta may be centuries old, but its message remains as relevant as ever: No one is above the law, and everyone is entitled to the protection of their civil rights and God-given liberties.