“There’s never been anything like it since Creation. Creation! That took six days. This was done in one. It was History made in an hour — and I helped make it.”

— Yancey Cravat, in Edna Ferber’s Cimarron

Word rang out across the Western world that at noon on the 22nd of April, 1889, upon the sound of a shotgun fired by a U.S. cavalryman, anyone with the guts and wherewithal to do so could rush into the Unassigned Lands in the center of present-day Oklahoma and claim their 160-acre spread from two million acres’ worth of government-designated tracts. In a singularly American feat of bravado and imagination, 50,000 people — including nearly a thousand African-Americans — from every state in the Union descended on the area to do just that.

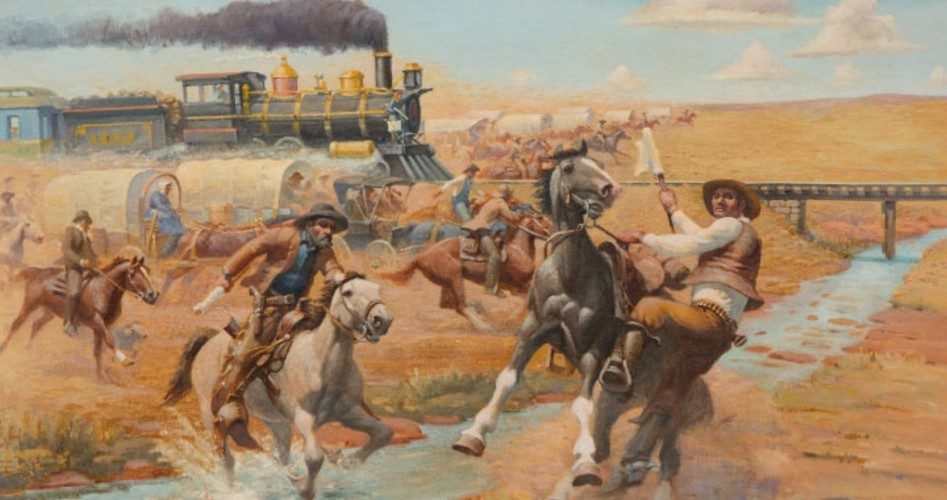

When the shotgun fired, they thundered across the line on horseback, mule, bicycle, and foot; in wagons; and even inside, outside, and on top of trains churning in from Texas and Kansas. Some got land, but most didn’t. There were fistfights, shootouts, and court battles. Many sneaked in early and claimed some of the best 160-acre tracts and town lots. These energetic folks earned the label “Sooners.”

By sundown on April 22, however, the entire country was settled, including the present-day towns of Oklahoma City, Norman, Stillwater, Kingfisher, and Guthrie, the latter designated as the territorial capital. More than 12,000 pioneers poured into Oklahoma City alone, which that morning had been a quiet railroad station on the prairie, sporting less than 10 structures near the dry banks of the North Canadian River.

The “Run of ’89” was an international sensation. “Unlike Rome, the city of Guthrie was built in a day,” trumpeted Harper’s Weekly, the dominant periodical of the era in the United States. “To be strictly accurate in the matter, it might be said that it was built in an afternoon. At twelve o’clock on Monday, April 22d [sic], the resident population of Guthrie was nothing; before sundown it was at least ten thousand. In that time streets had been laid out, town lots staked off, and steps taken toward the formation of a municipal government.”

Mrs. Welling Haynes, daughter of a widowed, sharecropping Kansas mother and “’89er,” left this witness to the memorable day:

We got in line ready to make the run when the signal was given. Then, real excitement began — everybody yelling, horses’ hoofs clattering, all in a hurry. Mother applied the whip and the horses started running. She didn’t try to guide them until we came to land on which very few people could be seen. She stopped the horses, jumped out of the wagon and stuck up her stakes. (This claim was one mile east of Crescent.) Mother then looked over her claim for a likely place to pitch our tent. She found a wide rocky canyon and a good spring of water.

The Unassigned Lands Run of 1889 was only the first, and not even the largest, in a series of such epic adventures. It continued a chain of events that stretched nearly to the founding of the American Republic and that would soon close the American frontier and produce the 46th state in the Union.

Indian Territory

To make sense of the Oklahoma land openings of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, one must explore the central role of the area in U.S. policy toward its aboriginal tribes during the preceding hundred years. As far back as the presidency of Thomas Jefferson at the dawn of the 19th century, the “Indian problem” had bedeviled a United States that was advancing across the North American continent and with an exploding population comprised of peoples from around the world.

The aboriginal American tribes, which had migrated thousands of years before from Asia, shared neither the Christianity, Western culture and education, technological advancement, nor social progress of the European immigrants who settled America. Numerous Christian missionary efforts went out to the hundreds of different tribes. Thousands of Natives embraced American culture and beliefs, and many assimilated into that society. The redoubtable Jefferson himself evinced a deep affection, respect, and concern for the Indians in numerous statements over many years. Yet his own words well articulated the intractable problem: “inability of the 2 cultures … one greater, one weaker … to mesh.”

The challenge was exacerbated by what Jefferson called “the interested and unprincipled policy of England,” which had “defeated all our labors for the salvation of these unfortunate people. They have seduced the greater part of the tribes within our neighborhood, to take up the hatchet against us, and the cruel massacres they have committed on the women and children of our frontiers taken by surprise, will oblige us now to pursue them to extermination, or drive them to new seats beyond our reach.”

Thus, American policy evolved into persuading, pressuring, and sometimes forcing the many tribes east of the Mississippi River to the other side of that great mid-continent divide. From at least 1820, “Indian Territory,” the area comprising present-day Oklahoma, except for its Panhandle, became the focus of government efforts — always reflective of American public sentiment — for the resettlement of the tribes. Trouble and sometimes tragedy ensued. The most infamous examples were the multiple Trails of Tears in the 1830s, which forcibly uprooted the Five Civilized Tribes (Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole) and cost thousands of Indian lives and untold suffering. Though the government often attempted humane treatment of the Natives — providing them free land, provisions, large financial payments, and military protection — again and again, its commitments to them faltered, though nearly always unintentionally. It was a frustrating, frequently maddening coalescence of genuine benevolence and even the Christian missionary spirit with misunderstanding, insensitivity, greed, and violence.

Why They Came

The stream of American citizens pioneering west for land and destiny gushed like a tidal wave following the end of the Civil War in 1865. Unclaimed frontier land was disappearing in the face of this millions-strong armed migration. The largest portion of land yet remaining was Indian Territory. There, only around 100,000 people — perhaps 80,000 of them Natives — lived on about 70,000 square miles of land. In comparison, the state of New York had around 4.3 million people living on 47,000 square miles.

In the face of such need and opportunity, the burgeoning U.S. populace demanded that their elected officials open the vast, sparsely inhabited lands previously reserved for the Indians to settlement. Elias C. Boudinot and other progressive-minded Indians, many of them mixed-bloods, urged their tribes to participate in, even excel at, the ways of the expanding American Republic, rather than shrink from its inevitable primacy.

Numerous other factors drove masses of American settlers west for a new, or last, chance. A decade of harsh and controversial post-war federal “Reconstruction” policies birthed financial overspeculation in the railroad industry, carpetbaggers, scalawags, robber barons, the Black Friday Stock Market Crash, the most corrupt presidential administration in U.S. history, the Gilded Age, the Ku Klux Klan, the Union League, and lasting enmity between the black and white races in the South.

Black Friday, the financial Panic of 1873, the nationwide Long Depression of 1873-79, the Panic of 1893, and a growing monopoly frenzy generated ongoing social and economic instability and upheaval for huge numbers of Americans. Also, the citizenry caught wind of the corruption, bribery, and other misbehavior that fueled many of the colossal fortunes accruing in the North and East, sections that had triumphed in the recent war.

Meanwhile, in 1866, the United States confiscated most of the western half of Indian Territory from the Five Civilized Tribes to punish them for their widespread alliance with the Confederate States of America during the War Between the States. Then the government forcibly placed other, mostly Great Plains or “wild” tribes, who were more nomadic, violent, and resistant to American culture, in bounded reservations on this land. This spawned a series of bitter, bloody wars between American horse soldiers and these Plains Indians, particularly the Comanche, Kiowa, Cheyenne, and Apache. By the late 1870s, the Indians were pacified, though a multitude of outlaws and gangs had rendered large swaths of Indian Territory a lawless enclave or “Robber’s Roost,” despite the Indian republics’ efforts to stop them.

Thus, as the U.S. military gained the upper hand in western Indian Territory, American pioneers increasingly agitated for land ownership there. Many of them migrated west from crowded, crime-ridden northeastern cities, many others from Southern lands destroyed by rampaging Union armies during the war, or lands just worn out from overplanting. The Southern ranks included thousands of blacks, many of whom sought a fresh start out from under the grim, deadly serious post-war Reconstruction conflict between Southern whites and the federal government.

The Boomers

Some of these white and black pioneers, known as “Boomers” because they were “booming” or trumpeting the settlement of Native lands, urged immediate opening of the vast, sparsely peopled southern plains of western Indian Territory. The scion of a famous and controversial family in Oklahoma history rose up as their standard bearer. Elias C. Boudinot, an accomplished mixed-blood Cherokee whose Cherokee father had defied the dominant powers of his tribe to bring thousands of his people to Indian Territory before the carnage of the Trail of Tears and suffered martyrdom for it, himself now defied the ruling powers of the whites and Natives alike.

In early 1879, Boudinot fired a written shot heard round the world through the editorial pages of the large and influential Chicago Times newspaper. In it, he challenged the U.S. government to open to the American populace as public domain the lands it took from the Indian republics in 1866, as he claimed that federal homestead laws demanded. Galvanized by this electrifying manifesto, would-be settlers poured into southern Kansas and southwestern Missouri, as well as the Red River Valley of north Texas, preparing to stake their claim in what Americans increasingly called the “Oklahoma Lands” or “Oklahoma.” Choctaw Indian chief and Presbyterian minister Allen Wright coined the latter term for the area. It means “Red People” in the Choctaw language.

A swashbuckling Union Army veteran named Charles Carpenter, who sported Custer-like long hair and buckskins, rallied hundreds of Boomers around himself and served notice that the birth of a new state loomed — with him as its apparent leader. Government officials intimidated Carpenter into backing off in 1879, and the army burned out early settlements of Boomers near present-day Oklahoma City.

As the 1880s arrived, however, a sea change roiled in Indian Territory. Gone were the buffalo — slaughtered by the millions to bring the wild tribes to heel in the Plains Indian Wars — and the rule of the Natives. Coming or already there were the U.S. Army, white entrepreneurs, a tidal wave of new Boomers, and the railroads, the colossus of 19th-century American industry. The government had subsidized the railroads with millions of dollars to help spur westward settlement, and the railroads needed passengers and cargo-shipping customers to, literally, pay their freight. This demanded American settlement of Indian Territory.

Maybe the government — earnestly attempting to honor its latest commitments to the Indians — could turn back Carpenter, and perhaps even David Payne, the more influential Boomer leader sometimes called the “Father of Oklahoma” who followed him. But U.S. industry and the American people now had their sights trained on the Oklahoma country. And history has shown many times that once that happens, for better or worse, there is no turning them back.

Twin Territories

The year after the Run of ’89, Congress passed the Oklahoma Organic Act, which legally divided Indian Territory into the Twin Territories. Oklahoma Territory now comprised roughly the western half of the original Indian Territory, that portion to the west of the five Indian republics’ lands and the smaller tribal enclaves to the northeast. The roughly eastern half remained Indian Territory. In response to settlers’ petitions, the Organic Act also established a republican form of representative government for Oklahoma Territory. It called for Republican President Benjamin Harrison to appoint a territorial governor, judges, and other officials, and for the people to elect a territorial legislature. And it designated Republican bastion Guthrie as temporary territorial capital.

Farther west, the Organic Act also folded the rough-and-tumble Panhandle (then variously called No-Man’s Land, the Public Land Strip, the Cimarron Country, or Robber’s Roost), into Oklahoma Territory. A haven for outlaws and fugitives until cowboys, cattlemen, and settlers cleared them out, its law-abiding citizens had applied unsuccessfully for territorial status as the Cimarron Territory. Now the government opened it for settlement under the provisions of the 1862 Homestead Act.

At this time, fewer than 30,000 people lived in the entirety of unsettled Oklahoma Territory — an area larger than many American states. This helps illustrate why the American people demanded its settlement. Indian Territory, meanwhile, though Congress strictly regulated its system of land ownership and it possessed an advanced system of constitutional law unlike the Oklahoma Territory, suffered rampaging lawlessness that the tribal governments who still possessed local authority were unable to stem.

Against this unsettled backdrop, the Unassigned Lands (a title minted by Boudinot in his famed newspaper article) Run, enabled by the nation’s legislative branch through the Springer Amendment to the Indian Appropriations Act, sponsored by Illinois Representative William Springer, was roundly considered a triumph of historic magnitude. The stage was set for more of them, including the biggest in history.

More Land Runs

Through the 1890s, whole new towns bustling with thousands of people rose up overnight from the Oklahoma prairie in a series of spectacular land runs, lotteries, auctions, and even a U.S. Supreme Court battle with Texas. In each case, the U.S. government apportioned members of the tribe that owned the land to be allotted their own quarter-section (160-acre) land parcel. Settlers received the remaining lands, for which the tribes were paid millions of dollars.

After the epochal Run of ’89 that settled the Unassigned Lands in the center of old Indian Territory came the September 22, 1891 land run immediately to the east in the Absentee Shawnee, Iowa, Potawatomi, and Sac and Fox country. Over 20,000 pioneers raced for land, but only 6,000 succeeded in securing it. These included William H. Twine, future African-American publisher as well as political and legal chieftain in Muskogee. Perhaps as many as a thousand blacks, including many residents of the all-black Oklahoma Territory town of Langston founded the previous year from land opened in the first run, sought claims in the 1891 event. It opened present-day Lincoln and Pottawatomie counties and portions of present-day Cleveland, Logan, Oklahoma, and Payne counties.

Just seven months later, on April 19, 1892, 25,000 Boomers thundered over the 3.5 million acres of surplus Cheyenne and Arapaho country in the Great Plains of western Oklahoma. This sprawling charge encompassed an area larger than Connecticut and Rhode Island combined. It remains as unique as it is forgotten. The participants included a hot air balloon and a six-horse team pulling a house. The well-known Kiowa warrior chief Big Tree, by now a Christian and leading advocate of peace between the Natives and whites, witnessed “as many (people) as the blades of grass on the Washita in the spring.”

Government officials reeled when no one claimed nearly three million acres of this land. A long and devastating drought, absence of railroads or any other roads, harassment by cattlemen who wanted the range, lack of building materials, scarce food, poor water, the barrenness of the land for crop growing, and worry about the fierce — and sometimes still-threatening — Cheyenne all contributed to this rejection of free property.

“About the only sure crop was the rattlesnake” went the saying. By the end of the decade, however, rugged pioneers of German, Irish, Scottish, Russian, English, African, and other stock had braved all challenges, often to the point of death, and carved their mostly forgotten names high in the annals of Oklahoma and American history to settle the area.

Cherokee Outlet Run

The greatest land run in history shook the earth across northern Oklahoma the following year, on September 16, 1893. One hundred thousand pioneers poured into the vast Cherokee Outlet, which stretched from the main Cherokee country in northeastern Indian Territory to No Man’s Land, the present-day Oklahoma Panhandle. Reserved as grazing and hunting lands for the tribe as part of their Indian removal package, the Outlet encompassed not only the sprawling lands the Cherokee leased to white cattlemen but also the small tribal enclaves of the Pawnee and Tonkawa, the latter numbering around 70 members.

Two factors generated drama in the Cherokee Run of a magnitude not found in other Oklahoma land openings. One was its sheer size, double the participants of the next largest, the Run of ’89. The other was the tense context in which it occurred. Historian Alvin O. Turner well described how years of drought across the South and Midwest, inadequate agricultural prices, and a national depression — the Panic of 1893 — brought thousands of desperate Boomers to the region, many of them financially destitute and many others close to starvation.

As the date of the run neared, the federal government required them to wait in line, often for days, in scalding heat just to register for the right to participate. Boomers, suffering from thirst, hunger, and sunstroke, fell ill, and some died in these lines. Twenty thousand still waited when federal officials closed down the registration booths.

Many Boomers endured mistreatment and even violence at the hands of soldiers and deputies tasked with controlling the enormous throng. Others suffered injuries and a few were killed when a chain reaction of stampedes broke out just prior to the start of the run. According to Turner, “Countless individuals were injured in the frantic (Cherokee Outlet) races following the starting guns or when mobs fought to board the trains or individuals jumped from the trains as they neared town sites.”

The great majority of the participants behaved well, and many displayed generosity and assistance toward one another. Enough did not, however, that the threat and sometimes the reality of violence hung over the entire proceedings like a dark cloud. As towns such as Ponca City and Blackwell sprang from the Oklahoma prairie within hours, cheating Sooners snatched many of the best claims, and most of those daring Boomers who made the Cherokee Outlet Run did not even get land. For those who did, the challenges had only begun, as Turner recounted:

The chaotic process of settlement continued to affect the region’s development long after the land run. Towns were over-built; farmers went broke on land unsuitable for farming…. Many claims were abandoned by the end of the year. There were, of course, success stories just as there had been instances of neighborly actions, generosity, even gallantry during the run. Yet even those who managed to secure good land soon learned that farmers’ opportunities were limited. The new towns, dependent on the farmers’ business, faltered in a changing American economy where the growth of industrialization had redefined the meaning of opportunity.

The Last Run

The final land run opened the Kickapoo country on May 23, 1895. This tiny tribe — fewer than 300 members, possessing around 200,000 acres — did not desire to be assimilated into white American culture. Their refusal to negotiate a treaty with the U.S. government on allotment delayed the process for years. The Kickapoos could forestall the inevitable no longer than May 23, 1895, however, when 10,000 more Boomers and Sooners charged into the area to claim a homestead or town lot. Wellston and McLoud are among the present-day towns that emerged from this run.

Once again, only a minority of the runners, which included numerous independent females as did previous runs, succeeded. More than ever before, though, due in part to a lack of race officials, Sooners foiled the Boomers. Perhaps as many as half the land seekers snuck in early, although scores were arrested and fined $1,000 apiece, an enormous sum in that day. Still, “Soonerism” had taken a large enough toll on the available land, triggered enough lawsuits, and generated such a wealth of anger and even violence that the government terminated land runs as a means of releasing the remainder of surplus Indian lands. The lottery and the auction would serve as the methods for future openings.

One other piece of Oklahoma Territory, the long-contested plains country in the far southwest corner, Greer County, came into the present-day Oklahoma fold in 1896. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the southern stream of Red River was its main course through the region — and thus was the original boundary of the Louisiana Purchase and now, Oklahoma Territory. This delivered the 1.5 million acres between it and the northern stream from Texas, which had claimed and partially settled it, to Oklahoma. Present-day towns such as Altus, Frederick, Hobart, Mangum, and Hollis would have been located in Texas had the verdict gone the other way.

Later Openings

Around 3.5 million acres of Comanche, Kiowa, Apache, Wichita, and Caddo tribal land in southern Oklahoma Territory, along with nearly two million acres of Osage, Ponca, Kaw, and Otoe-Missouri tribal land comprising the northeast portion of the territory, remained unallotted to individual tribal members and unapportioned to American settlers at the dawn of the 20th century. Congress remedied this with more great land openings — through lottery.

In 1901 came the Wichita and Caddo lands around present-day Caddo County and the Kiowa-Comanche-Apache (K-C-A) lands around present-day Comanche and Kiowa counties. Over 135,000 prospective homesteaders and town citizens registered for property tracts, hoping to hear their names called among the listings of 13,000 lots pulled from large boxes. Following the awarding of these lots, sales of town lots in the new county seats of Anadarko (Caddo), Lawton (Comanche), and Hobart (Kiowa) commenced. Nearly $750,000 from these sales financed construction and improvement of roads, bridges, and courthouses in these counties.

At least two legendary Oklahomans — future U.S. Senator and anti-New Dealer Thomas P. Gore and famed lawman Heck Thomas — put down stakes as thousands of people raised the new town of Lawton up from the southwest Oklahoma plains on the day of its birth, August 6, 1901. The two men developed a close friendship. Though he was blind, Gore’s recollection of the signal experience, when he and Thomas at first lived in tents on the heretofore wild and dangerous prairie, provides an enduring window for future generations into pioneer Oklahoma:

I located at Lawton before there was any Law-ton. There were only two little shacks on the town-site when I located my tent on the Eastern Boundary which was then called ‘Goo-goo’ avenue. The blue grass was waist high on most of the town-site, particularly where there were “hog-wallers.” The hard mesquite occupied part of the town-site.

In 1904, much smaller portions of Ponca, Otoe, and Missouri lands were allotted to individual tribal members. Settlers purchased the remaining 51,000 acres. Osage and Kaw Indians received individual allotments of their tribal lands in 1906, with none left for settlers. At the end of 1906, the federal government auctioned off 480,000 acres of K-C-A range along Red River through a sealed bid. This “Big Pasture” ranching country had served as a hunting and grazing reserve for these tribes since the 1901 allotment and sale of their remaining southwest Oklahoma lands.

Good and Bad

Repeating a recurrent theme of American history, these memorable events spawned opportunity and thrilling history, as well as injustice, loss, and sorrow. Dust clouds billowed and the earth shook when thousands of horses, mules, wagons, and other vehicles thundered across the prairie toward new homesteads and the building of an American state during the K-C-A opening. Yet Christian missionaries who had labored among the Comanche, Kiowa, and Apache on those enormous reservations, “lamented the high crime rates, drunkenness, unsanitary conditions, and diseases” strewn in these pioneers’ wake, according to historian Benjamin R. Kracht.

Numerous white voices joined the Indians in opposing the K-C-A opening. They included Indian Agent James Randlett, Fort Sill Cavalry Commander Hugh Scott (namesake of Lawton’s Mount Scott), Texas cattlemen who grazed herds there, and Baptist, Presbyterian, Mennonite, Roman Catholic, and Methodist Episcopal, South missionaries.

Kiowa Chief and Christian convert Lone Wolf (the younger adopted son of famed warrior and chief Lone Wolf, the elder) mounted a brilliant, years-long legal battle with the federal government over the K-C-A opening that roared all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. That body ruled against the Kiowas, citing the Fifth Amendment of the Bill of Rights for their remarkable admission that “the power exists to abrogate the provisions of an Indian treaty.”

Indeed, controversy attended the entirety of the U.S. government’s dealings with the Indian tribes of America from the 1600s onward, often with justification. Some Oklahoma schools have removed land run celebrations and even activities from their curriculum. Modern Americans, however, while studying the lessons of the past in an objective, clear-eyed manner, would do well to ponder the consequences had brutal tribes such as the Comanche — feared and loathed not just by white and black Americans, but by other Native tribes whose members they raped, tortured, murdered, and enslaved — won control of Oklahoma and other states from Western and Christian civilization.

As alluded to earlier, among the innumerable beneficiaries of Oklahoma Territory land openings were thousands of African-American pioneers. In an era of national segregation, discrimination, and racism against blacks, the Oklahoma country offered unparalleled opportunities for this struggling race. Courageous black visionaries and elected office holders such as Edward P. McCabe, Green I. Currin, and Albert Hamlin spearheaded the founding of numerous all-black towns in the Twin Territories, as well as their own state-supported Oklahoma Colored Agricultural and Normal University. Now Langston University, the school remains the westernmost historically black college in America. Perhaps best of all, according to historian Jimmie Franklin, sourcing the U.S. Bureau of the Census regarding the 1910 census, blacks owned more than 1.5 million acres of land in future Oklahoma by 1905, much of it in Oklahoma Territory.

Statehood

The land runs, lotteries, and auctions that opened Oklahoma Territory launched a new chapter of drama for its pioneers. The farmers took hold of plains and prairie land, much of which was bereft of basic natural resources their counterparts possessed nearly anywhere else in America. These included water for people, stock, and crops; trees for materials for homes, outbuildings, and implements; and foliage of all sorts for wind, dust, and water breaks. By the end of the 1890s, nearly half the farmers in western Oklahoma who did still own their land — many of them striving to follow better agrarian practices — had mortgaged it.

Despite these and innumerable other challenges and heartbreaks, however, between 1900 and 1910, over a million white, black, Indian, Hispanic, and Asian residents birthed, in the words of one of Oklahoma’s Founding Fathers, “not just a new state, but a new kind of state.” During the same period, one of the greatest oil booms in history gushed forth from the land loved by so many of those people.

The American population mushroomed during this decade due to increased immigration and high domestic birthrates. The nation’s vast frontier was mostly secured by the dawn of the new century, despite the fact that much of the South was still stymied by the devastation of the War Between the States and its aftermath. Thus, the sweeping tracts of free land, moderate climate, and opportunity to build new families and a new state alike gleamed like a beacon of last chance-hope and paradise to people across the United States and even other nations.

Perhaps the dean of Oklahoma historians, Edward Everett Dale, who himself pioneered “Old Greer County” in future southwest Oklahoma with his family as a teenager, pronounced the most fitting benediction for this remarkable time and place, when men, women, and children thundered across the American landscape in pursuit of all which that iconic vision dangled before them:

The pioneers who came to the West (sought) for that most precious of all human material possessions, a home. Largely speaking, this home seeker is the forgotten man in the annals of the American West…. Yet he was by far the most important factor in the conquest and development of our American empire.

His way of life has vanished and is largely forgotten by all but a comparatively few people. It is, however, a part of our social history and as such should be preserved and cherished. It was the pioneer settlers who won the West when the wooing was difficult and sometimes dangerous, and most of them now sleep in its soil.

John J. Dwyer is author of The War Between the States: America’s Uncivil War and the upcoming The Oklahomans: The Story of Oklahoma and Its People.

This article is an example of the exclusive content that’s only available by subscribing to our print magazine. Twice a month get in-depth features covering the political gamut: education, candidate profiles, immigration, healthcare, foreign policy, guns, etc. Digital as well as print options are available!