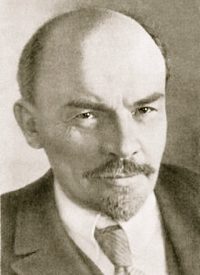

Communism, for a long time, was simply “Bolshevism” in the western world. The Russian term means “majority” and it originated during the Second Party Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party in Brussels in 1903. Party Chairman Vladimir I. Lenin caused a procedural vote during the congress regarding who should be allowed to join the party. Lenin favored limiting membership in the party to professional revolutionaries, while his opponents favored allowing in those who generally supported the party but who were not constant agitators. Lenin won the procedural vote and so cast his faction thereafter as “Bolsheviks,” while the side which lost was called “Mensheviks” or “minority.”

All were communists. Marx himself used the term “communist” and “socialist” interchangeably. The nuanced differences that we see today between communists and socialists have nothing to do with different ultimate goals. All want to destroy free enterprise and establish control of a political party which will rule in the interest of the proletariat. The Russian Social Democratic Labor Party was, simply, the Communist Party of Russia, and that continued after the Bolshevik-Menshevik split.

In fact, a perusal of the names given to communist parties around the world shows that communists simply use a particular name as a way of appearing to be what they wish. The communist party in East Germany was called the “Socialist Unity Party”; in Poland it was called the “Polish United Workers Party”; in Hungary, the “Hungarian Working People’s Party”; and in North Korea, the “Workers Party of Korea.”

At the time of the Bolshevik/Menshevik split, many Marxists in Europe were “Fabian Socialists” who urged their fellow ideologues to adopt the tactics of Quintus Fabius when he confronted Hannibal in the Second Punic War. Rather than try to defeat the brilliant Carthaginian general in the field, Fabius followed his army around Italy, slowing depleting Hannibal’s forces and harassing his troops until Hannibal was whittled down to nothing. The brand of Marxism we call “socialist” or “progressive” today is very much alive, advocating gradual measures which ratchet our nation toward an imagined Marxist utopia.

What was true in 1912 and in 2012 was true throughout the last century. Consider, for example, the partisan breakdown of the Chamber of Deputies in France in 1930 (other years show very similar results). These are the parties and their strength in that chamber:

Radical and Radical Socialist — 118 members

Socialist — 100 members

Republican-Democratic Union — 97 members

Left Republican — 64 members

Radical Left — 52 members

Republican Socialist and French Socialist — 35 members

Democratic and Social Action — 30 members

Popular Democratic — 19 members

Unionist and Social Left — 17 members

Independent Left — 15 members

Communist — 10 members

Belonging to no group — 45 members

Not inscribed — 7 members

Conspicuous by their absence are any parties which lean toward Christianity, liberty, free enterprise, or what is called today “conservative” values. Absent also are any parties which support a republic rather than a democracy. Every party but one has in its name one or more of the following words: “radical,” “socialist,” “democratic,” or “left.” The one party which does not have one of those terms is the Communist Party. Yet these political parties, all formally bound to Marxist thinking, were incapable of combining to form a majority in the chamber — and so form a government — that lasted more than a few months. These traits — morphing nominal names for Marxist movements and in-fighting for power — showed up in the history of Bolsheviks in Russia.

In January 1912, 100 years ago, the Bolshevik faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party at the Party Conference in Prague formally banished Mensheviks and created a new party. It was first called the All-Russian Communist Party, then the All-Union Communist Party, and finally the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. It was this political movement which overthrew the Kerensky government, the successor to the Tsars, during the November 1917 Revolution (or, more properly, a junta by violence against a recognized government).

What were the themes of Bolshevism? Some of its maxims give clear clues: “The worse, the better” (meaning that the more wretched the human condition can be made to be, the quicker Marx’s imagined revolution of the proletariat would occur). Another that may ring familiar today is “The more innocent, the more guilty” (which reflects that justice is “social justice” and that individual trial of the accused, part of the American system of justice inherited largely from the British system of rights, has no purpose). Or, as Lenin put it: “We must be ready to employ trickery, deceit, law-breaking, withholding and concealing truth. We can and we must write in a language that sows among the masses hatred, scorn, and the like towards those who disagree with us.”

Another theme is the primacy of the political party over the government. Howard Fast, a Hollywood screenwriter who was a communist and had won the Stalin Prize, abandoned Communism and wrote afterwards: “Russia provided the world with a new situation … A modern industrial complex was created within a nation that literally had no functioning government, as we know government, but merely a framework for the administration which the Communist Party controls,” He later observed, “There was no Soviet government; there is none today.” Lenin said: “Without instructions from the Central Committee of our party not one state institution in our republic can decide a single question of importance as regards matters of policy and organization.” The well-known Australian anti-communist Dr. Fred Schwartz in 1962 explained it well: “The difference between the State and the Party is rarely understood. The head of the Russian State may be an insignificant individual. When Stalin was all-powerful within Russia … He was merely Secretary of the Communist Party.”

The ultimate goal, as George Orwell so chillingly explained in his chilling novel 1984 through the mouth of “Inner Party” member O’Brien as he tortured Winston Smith in the cells of the Ministry of Love, was this:

The German Nazis and the Russian Communists came very close to us in their methods, but they never had the courage to recognize their own motives. They pretended, perhaps they even believed, that they had seized power unwillingly and for a limited time, and that just round the corner there lay a paradise where human beings would be free and equal. We are not like that. We know that no one ever seizes power with the intention of relinquishing it. Power is not a means, it is an end. One does not establish a dictatorship in order to safeguard a revolution; one makes a revolution in order to establish a dictatorship. The object of persecution is persecution. The object of torture is torture. The object is power is power.”

A review of the current condition of politics and the creeping hand of Big Brother in our lives makes it plain that the Bolsheviks, by whatever chameleon name they choose to use, are still in power.