In order to recover from the debt incurred in fighting the French in the Seven Years’ War (Britain’s national debt nearly doubled during that protracted global conflict), the king and parliament decided to impose a series of taxes on America. The Colonists’ opposition to these taxes was not based on the amount; rather they refused to submit to a scheme of revenue raising that directly violated their centuries-old rights as Englishmen, particularly those rights recorded in the Magna Carta.

Apart from the taxes, however, King George II (and his son and successor, George III) issued orders known as general writs of assistance. In simple terms, these writs authorized law enforcement and other representatives of the Crown to enter buildings to search for contraband without obtaining a warrant. This did not sit well with American Englishmen, and they were determined to boldly refuse to be subjected to searches that exceeded the constitutional authority of the king and Parliament.

Another unconstitutional aspect of these writs was the fact that they were not specific; that is to say, they did not name the place to be searched, the things to be searched for, or the people who aroused the suspicion of illegal behavior.

These warrantless “warrants” were served on not only Americans, however — British subjects at home were harassed in similar fashion. Enter John Wilkes.

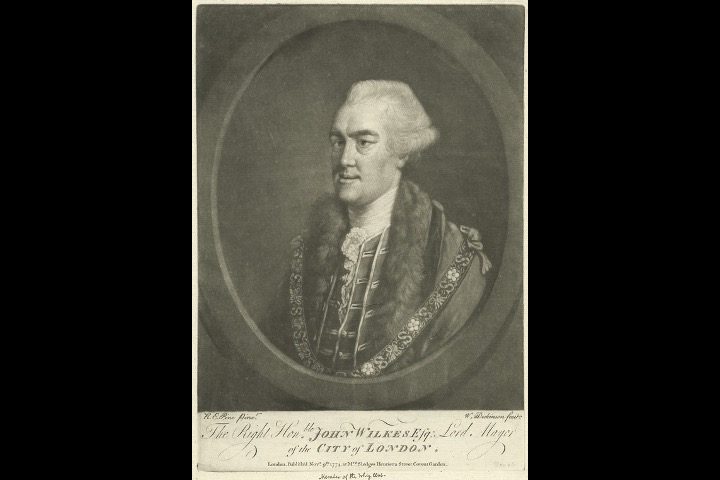

John Wilkes, a name that resonates in the annals of British history, was more than just a politician; he was a symbol of unwavering defiance in the face of tyranny. Born on October 17, 1725 in London, Wilkes embarked on a tumultuous journey that would ultimately see him challenge the might of King George III’s government and become an enduring icon of free speech.

In 1763, John Wilkes found himself on a collision course with the British Crown. The catalyst for this confrontation was Number 45 of his audacious publication The North Briton, a weekly periodical that broke away from the usual sycophantic tone of the era’s publications and dared to question the actions of King George III and his ministers.

The publication of The North Briton Number 45 in 1763 catapulted John Wilkes into a tumultuous legal and political battle. This provocative publication criticized King George III’s ministers and their policies, specifically taking issue with remarks delivered by the King in his address to Parliament.

Wilkes was careful to not directly attack the king; rather, he criticized the king’s ministers and their actions. However, King George III and his government took this criticism as an affront to the Crown’s authority, viewing it as an attack on the monarchy itself.

In the aftermath of the publication, the British government obtained a general warrant, a sweeping and controversial document that lacked specific details, to arrest and apprehend those responsible for the daring publication.

On Easter Sunday of 1763, Wilkes was arrested and subjected to a highly invasive search under the authority of this general warrant. The arrest set the stage for a protracted legal and political struggle. This warrant was alarmingly broad, as it did not specify the individuals, places, or items to be searched. Instead, it granted authorities sweeping powers to identify and seize the perceived troublemakers.

The roots of this dispute can be traced to a royal address to Parliament in 1763, a speech authored by the king’s ministers. Being a member of the English Parliament, Wilkes took it upon himself to critique the speech’s content, taking issue with the government’s policies and the king’s apparent disregard for the people’s interests.

Wilkes’ arrest and subsequent persecution galvanized his supporters, who saw this as an affront to the principles of free speech and individual liberties. They mounted protests and engaged in legal challenges to contest his treatment. The central issue in these challenges was the violation of fundamental rights, especially the right to criticize the government without fear of retribution.

One of the pivotal legal battles was Wilkes v. Wood, which focused on the legality of general warrants. The case resulted in a landmark decision that declared general warrants to be illegal, establishing a crucial precedent for the protection of civil liberties.

Wilkes faced further persecution, though, including his expulsion from Parliament and being declared an outlaw.

John Wilkes’ case and the legal battles surrounding it had a lasting impact on the development of civil liberties and freedom of speech in Britain. It underlined the importance of holding those in power accountable, and Wilkes became an enduring symbol of the struggle against government oppression. His legacy serves as a testament to the enduring principles of free speech and personal liberty, and his ordeal endures in the annals of British history.

Wilkes’ legacy also extends beyond the boundaries of England, however. Upon winning his freedom in court, he was reelected to Parliament for several terms. The number “45” — the issue number of The North Briton that set off the search and the prosecution — became a symbol for liberty on both sides of the Atlantic.

The official website of Colonial Williamsburg adds to the account of Wilkes’ fame and the association of “45” with the struggle to restore individual liberty:

Energized by Wilkes’s victory, the others scooped up by the general warrant sued the government — an unprecedented action — and won, precipitating what scholar Arthur Cash calls “a momentous shift in the locus of power in government” from the privileged to the masses. Soon cries of “Wilkes and Liberty!” were heard across London, and the author of No. 45 embodied a movement of revolt against the government. The number 45 became a symbol of radical politics: one liberty-loving parson delivered a sermon on the forty-fifth verse of Psalm 119, “I will walk in Liberty, for I keep thy precepts.”

In America, our Founders not only praised Wilkes for his courage, but used his experience as a cautionary tale that informed their own efforts to shield the citizens of their new union from similar deprivations of the fundamental right to be free from warrantless general writs.

Wilke’s legacy includes being the namesake (along with Isaac Barre) of Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, as well as Wilkes County, Georgia.

So, today, in honor of the birth of John Wilkes, a hero to our Founding Fathers and a staunch defender of liberty, let us call out “45!” and use the funny looks as an opportunity to teach our friends and neighbors about John Wilkes.