1381 and the Price of Tyranny: Lessons From the English Peasants’ Revolt

In the long catalog of uprisings against tyranny, one chapter often overlooked — but no less instructive — is the English Peasants’ Revolt of 1381.

Though distant in time, the cause and character of that revolt echo loudly in our present condition: oppressive taxation, ruinous foreign wars, and a government grown unaccountable to the people it purports to serve.

We would do well to remember that the flames of rebellion are not kindled in a day.

They are fanned over time by injustice, arrogance, and a persistent disregard for the natural rights of man.

The uprising of 1381 was no exception. It was a righteous protest against the abuse of power — a rebellion born not of ambition, but of desperation.

The roots of the revolt lie in the economic and political decay of 14th-century England, a decay accelerated by the hubris of kings and the greed of the ruling elite.

The Poll Tax

England had, for decades, been engaged in costly military campaigns on the Continent — the so-called Hundred Years’ War — draining the kingdom’s coffers and devastating its countryside.

To finance these foreign adventures, the crown turned inward. But not to cut its own excesses — to extract more from the already overburdened commons.

It was taxation without mercy, and often without consent. Chief among these injustices was the poll tax — a flat levy imposed on every man, woman, and child regardless of income or station.

This was not a tax aimed at raising needed revenue. It was a tax aimed at breaking the backs of the peasantry.

The third imposition of the poll tax in 1381 was the final insult, a triple burden within four years, met not with resignation but with righteous fury.

Out of that fury rose figures who would shake the kingdom. One such man was Wat Tyler, a blacksmith from Kent who quickly emerged as a charismatic leader of the rebels.

Another was the radical priest John Ball, who famously preached, “When Adam delved and Eve span, who was then the gentleman?”

It was a sermon not of envy, but of equality before God. It was a declaration that hereditary hierarchy had no moral claim to authority.

The Revolt

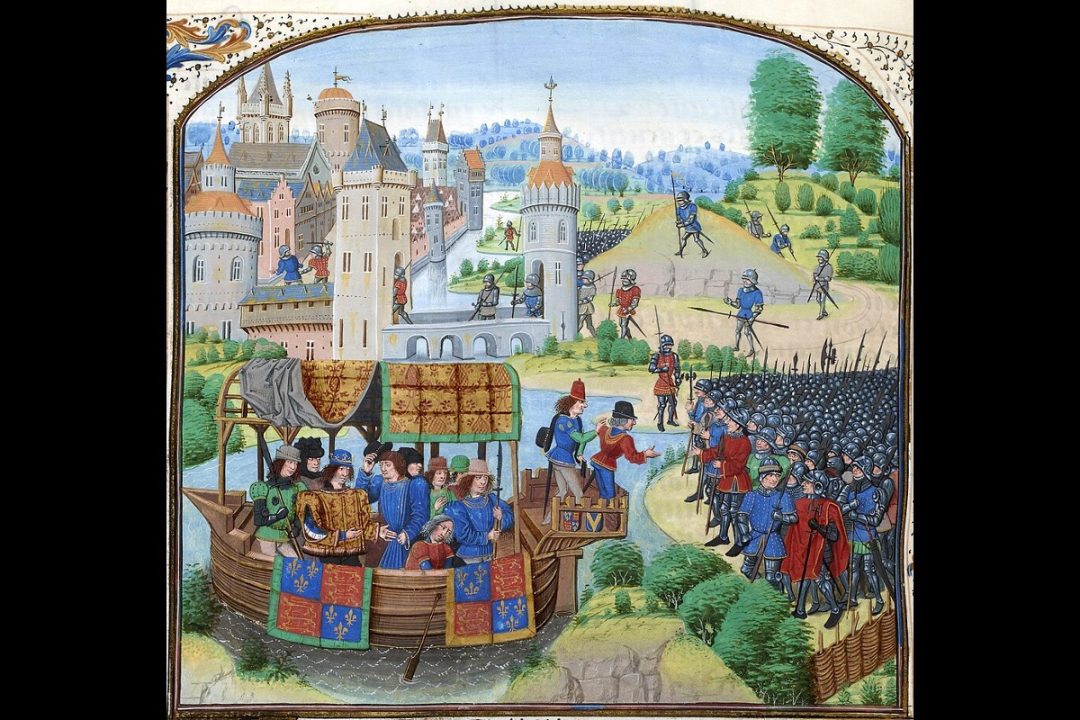

In June 1381, the peasants marched. From Kent and Essex, thousands converged on London, demanding the end of serfdom, fair wages, and the abolition of the poll tax.

They were not a rabble of looters; they were a body politic awakened, a multitude demanding that the social contract be rewritten on terms of justice, not tyranny.

What they found instead was deceit.

King Richard II, then only a teenager, met with the rebel leaders and feigned sympathy.

He promised reforms, agreed to charters of freedom, and swore that their grievances would be addressed.

Wat Tyler, trusting in the king’s words, met with him again in Smithfield. But there, in the open square, he was struck down, murdered under a flag of truce.

The king’s soldiers then descended on the now-leaderless crowd. The charters were revoked. John Ball was hunted down and hanged.

Thousands of peasants were executed or silenced through fear.

And thus, the revolt ended, not in triumph, but in treachery.

But let us not mistake defeat for failure. The Peasants’ Revolt did not reshape England overnight, but it did plant a seed.

The cause of liberty, once stirred, does not slumber long. Within decades serfdom would fade, and the rights of commoners would slowly expand.

The very idea that government must be accountable to the governed — borne on the backs of those brave rebels — would smolder until it ignited centuries later.

Conclusion: The Echo of 1381 in Our Time

What, then, shall we say of our own time?

Are we not living once again under the weight of unjust taxes imposed to finance foreign military adventures?

Is not our federal government — like the Plantagenet monarchy of old — more interested in expanding its influence abroad than honoring its responsibilities at home?

We are told that liberty must be sacrificed for security, that endless war is the price of peace, and that we must foot the bill for imperialism under the guise of “global democracy.”

But the Founders of our own republic — men well-versed in the lessons of English history — warned against just such folly.

James Madison wrote that, “of all the enemies to public liberty, war is perhaps the most to be dreaded, because it comprises and develops the germ of every other.”

He knew what Richard II never learned. He knew that a government that taxes its people to fund foreign conquest will inevitably lose both treasure and trust.

The Peasants’ Revolt teaches us that tyranny does not arrive overnight.

It creeps in through taxes, consolidates through war, and triumphs through deception.

But it also teaches us that the people — when they remember who they are — can resist.

The men and women of 1381 knew they were being plundered and lied to. They rose — not as revolutionaries, but as stewards of a natural right to be free from abuse.

Their courage, though crushed, echoes still.

May we learn from their example. May we reject the seductive chains of fiat taxes and foreign entanglements.

And may we, in our own time, have the courage to rise — not in violence, but in virtue — with one voice, one demand: that government return to its rightful bounds, and that liberty once again be the law of the land.