Journalist, author, and three-time presidential candidate Patrick J. Buchanan reminisced about his half-century in journalism Thursday night, while lamenting what he described as the decline of the “e pluribus unum” (out of many, one) ethos in America. Returning to the state where he won the opening primary in the 1996 presidential campaign, Buchanan told an audience in Concord, New Hampshire that a growing factionalism is sundering the foundations of national unity.

“Are we still one nation indivisible or are we permanently Red State America and Blue State America?” asked Buchanan, the keynote speaker at the First Amendment Awards ceremony of the Nackey S. Loeb School of Communications. The breakdown is particularly troublesome for the “red state,” or Republican faction, he said, since Republican voters are mostly Christians of European descent, a shrinking percentage of the American population. Newer waves of immigrants and their descendants, along with African-Americans, vote consistently Democratic, he said, noting that 18 states have voted Democratic in the last six consecutive elections. Buchanan dwelt on the role of the news media, particularly the TV networks, in what he described as “the fragmentation of American society.”

Television “killed the evening newspapers,” he said, recalling that by the late 1960s two-thirds of the American people were relying on television as their main source of news. Having gone to work writing editorials for the St. Louis Globe-Democrat shortly after graduating from the Columbia School of Journalism in 1962, Buchanan recalled that in the autumn of that year, former Vice President Richard Nixon, defeated as a candidate for governor of California, bitterly assured members of the state and national press corps they wouldn’t “have Nixon to kick around anymore.” Two years later, former President Dwight D. Eisenhower, speaking at the Republican National Convention in San Francisco, ignited a spontaneous demonstration of anger among the delegates toward the press corps when he spoke of “sensation-seeking columnists and commentators.” The conservative war against the “liberal bias” of the major news media was underway.

While serving as a senior advisor in the Nixon White House in 1969, Buchanan noted with alarm the negative analysis the network news commentators provided immediately following Nixon’s “Silent Majority” address to the nation on the Vietnam War. Describing how every presidential speech or action was being “filtered” through the news media, Buchanan recalled telling the president, “They’re standing on our windpipe.” In response, Buchanan wrote a strongly worded criticism of the TV commentators and their “instant analysis” for Vice President Spiro Agnew, which was broadcast live on network television when Agnew delivered the address to the Midwestern Regional Republican Conference in Des Moines, Iowa. Buchanan recalled that Nixon, in reviewing and editing the speech, observed with a chuckle, “This’ll tear the scab off the (expletive deleted).” The expletive he deleted, Buchanan explained, was Nixon’s pet name for the news media.

While much of the media denied the accusation of bias, Buchanan said the controversy sparked by the criticism from Agnew and others prompted many newspapers and TV talk shows to feature more conservative opinion writers. He cited the rise to prominence of conservative media stars like George Will and James J. Kilpatrick and noted that William Safire, his fellow speechwriter in the Nixon White House, became an op-ed columnist for the New York Times. Buchanan’s career followed a similar path, leading to a widely syndicated column and several years as co-host of the former CNN show, Crossfire. He remains a fixture on the syndicated program, The McLaughlin Group. Today, he said, a larger, more diverse media both reflect and perpetuate the fragmentation he described.

“You’ve got Rush [Limbaugh] and [Sean] Hannity and Laura [Ingram] versus NPR and Big Bird,” he said, with each holding its own constituency. In one of several observations that sparked laughter, Buchanan recalled President George W. Bush saying, “They’ve got these new things called the internets.” The Internet, Buchanan said, has enabled consumers of news to seek out the stories and opinions congenial to their own biases.

“They create their own newspapers, if you will, where they only have to read and understand and know what their side is saying. So more and more people are living in these separate bubbles of their own making,” he said.

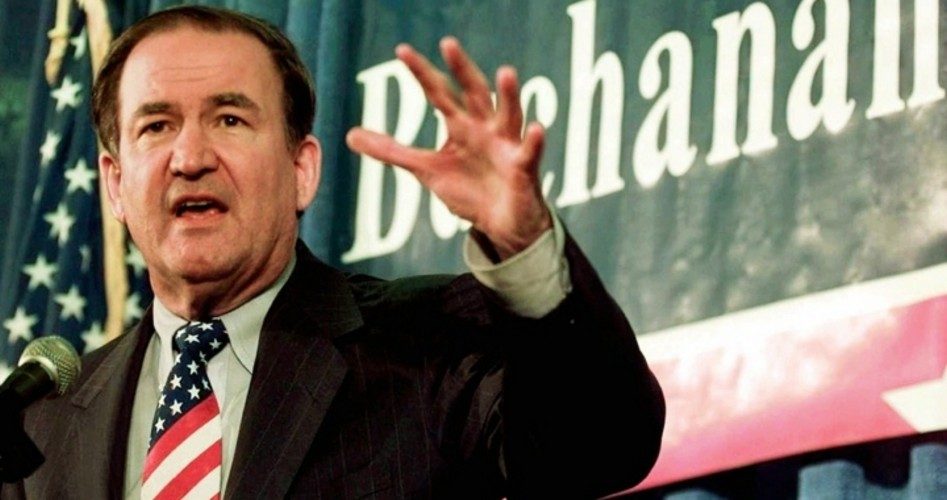

Buchanan was on familiar turf in New Hampshire, where he made several forays during his three campaigns for president, starting in 1992, when the journalist-turned-candidate mounted a late but surprisingly strong primary challenge to incumbent President George H.W. Bush, garnering 37 percent of the vote in New Hampshire’s first-in-the-nation primary. Four years later, he upset perceived frontrunner and eventual nominee Bob Dole in New Hampshire, but failed to win in any of the following contests. He left behind some memorable phrases, dubbing his campaign bus as “Asphalt One” and describing his supporters “peasants with pitchforks,” coming over the hill to challenge the party establishment.

In his victory speech in New Hampshire in ’96, an exuberant Buchanan called on his supporters to “mount up and ride to the sound of the guns!” Several losses later, he recalled, someone reminded him, “You didn’t tell us we were riding into Little Big Horn.”

The First Amendment Awards are presented annually at Concord’s Capitol Center for the Arts by the Loeb School of Communications, founded by Nackey S. Loeb, the late publisher of the New Hampshire Union Leader and Sunday News. Buchanan acknowledged the papers’ editorial support during his talk Thursday night. “Without the Manchester Union Leader and Nackey Loeb and (current publisher) Joe McQuaid, there would have been no Buchanan campaign,” he said.

Admitting he is no “historical optimist,” Buchanan claimed to find some hope for America in the prophecy of 19th century German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, who reportedly spoke before his death of a special providence that watches over “drunkards, fools and the United States of America.”

“Let’s hope it’s so,” Buchanan concluded.

Photo of Pat Buchanan in his 1996 campaign for the Republican nomination for president: AP Images