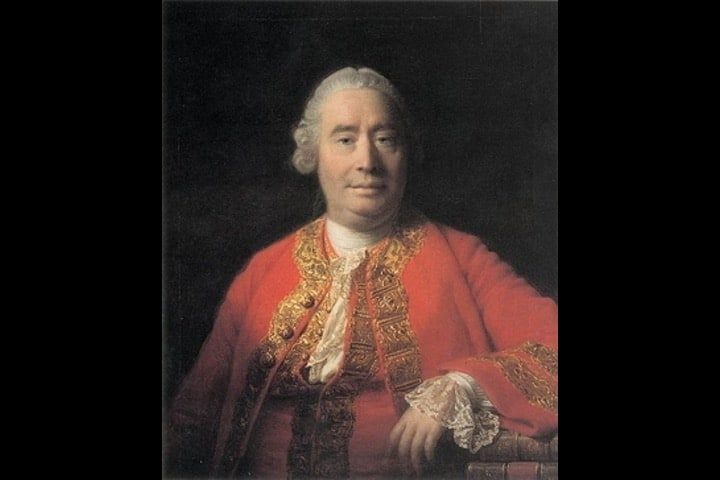

“Nothing appears more surprising to those, who consider human affairs with a philosophical eye, than the easiness with which the many are governed by the few.” — David Hume

In the months leading up to the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in May 1787, James Madison received chests of books from his best friend, Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson was living in Paris, providing him with ready access to scores of bookstores and libraries filled with the world’s finest written works on the subjects of politics, history, and government. Taking advantage of his friend’s generosity and good fortune, Madison asked Jefferson to send him crates full of the best of these books, books he would read, ponder, and pore over during an extraordinarily eventful summer.

Of all the authors whose books Madison pored that summer, there was one that earned the distinction of being the man whom Madison read the night before George Washington gaveled the convention into session: David Hume.

David Hume was an 18th-century Scottish philosopher and historian, widely regarded as one of the most important figures in the Enlightenment movement. Born in Edinburgh, Scotland, on May 7, 1711, Hume was the second son of a wealthy family. He began his formal education at the University of Edinburgh, but left after just two years to pursue a career in business. However, after a failed stint in business, Hume turned his attention to philosophy.

Hume’s philosophical writings were wide-ranging, but his most significant contributions were in the areas of epistemology, metaphysics, and ethics. He is perhaps best known for his skepticism, particularly his argument that causation is not a necessary connection between events, but rather a habit of the mind based on our past experiences. This view led him to reject many of the traditional arguments for the existence of God, and to develop a naturalistic approach to ethics.

In addition to his philosophical work, Hume was also a prolific historian. His most famous work in this area is “The History of England,” which covers the period from the invasion of Julius Caesar to the Glorious Revolution of 1688. Although his approach to history was often criticized for its lack of objectivity, Hume’s work was groundbreaking in its use of primary sources and its emphasis on social and economic factors.

Hume’s influence on philosophy and intellectual history cannot be overstated. His ideas were particularly influential on Immanuel Kant, who famously said that Hume had “awakened [him] from [his] dogmatic slumber.” Hume’s skepticism and naturalism also had a profound impact on later thinkers, such as Friedrich Nietzsche and Bertrand Russell.

Despite his immense contributions to philosophy and history, Hume was not always well-received in his own time. His skeptical views on religion and morality led many to accuse him of atheism and immorality, and he was denied a professorship at the University of Edinburgh because of his views. However, his work continues to be studied and debated to this day, and his legacy as one of the most important thinkers of the Enlightenment remains secure.

A forgotten aspect of Hume’s legacy, however, is the honor he received of being the man whose worked James Madison turned to the night before he would begin debating the document that would become our current Constitution.

Specifically, Madison read and took notes on Hume’s “On the Idea of a Perfect Commonwealth.” Such essays describing utopian republican societies were very influential on the Founding Fathers, particularly on James Madison, who believed he was being tasked by Heaven with crafting a constitution for a perpetual confederation. Through his study of Hume (and others), Madison believed he could find the key to inoculating America against the diseases that infected and destroyed past societies. Indeed, it could be said that during this time, Madison behaved like a coroner, a specialist responsible for examining the lifeless bodies of the self-governing societies of the past, in order to prevent the United States from succumbing to the maladies that shortened the lives of its freedom-loving forerunners.

Hume’s “On the Idea of a Perfect Commonwealth” was a target-rich environment for someone like Madison, searching for tools with which he could build the best possible confederation of sovereign republics.

I should add that, in addition to Madison, other Founding Fathers likewise looked to the eminent Scotsman for wisdom and warnings.

In The Federalist No. 85, Alexander Hamilton includes an extensive quotation from Hume’s essay “The Rise of Arts and Sciences.” In introducing the quotation, Hamilton describes Hume as “a writer equally solid and ingenious.”

Additionally, as with so many of the leading lights of the day, Benjamin Franklin was a friend and frequent correspondent of David Hume.

Now — enough of biography and recommendations from the Founding Fathers. Here are a few selected quotations from the solid and ingenious David Hume.

On the Concept of Consent of the Governed:

The force which now prevails, and which is founded on fleets and armies, is plainly political and derived from authority, the effect of established government. A man’s natural force consists only in the vigor of his limbs and the firmness of his courage, which could never subject multitudes to the command of one. Nothing but their own consent and their sense of the advantages resulting from peace and order could have had that influence.

But philosophers who have embraced a party — if that be not a contradiction in terms — are not content with these concessions. They assert not only that government in its earliest infancy arose from consent, or rather the voluntary acquiescence of the people, but also that, even at present, when it has attained its full maturity, it rests on no other foundation. They affirm that all men are still born equal and owe allegiance to no prince or government unless bound by the obligation and sanction of a promise. And as no man, without some equivalent, would forego the advantages of his native liberty and subject himself to the will of another, this promise is always understood to be conditional and imposes on him no obligation, unless he meet with justice and protection from his sovereign. These advantages the sovereign promises him in return; and if he fail in the execution, he has broken on his part the articles of engagement, and has thereby freed his subject from all obligations to allegiance. Such, according to these philosophers, is the foundation of authority in every government, and such the right of resistance possessed by every subject.

Force is always on the side of the governed, the governors have nothing to support them but opinion. It is therefore, on opinion only that government is founded; and this maxim extends to the most despotic and most military governments, as well as to the most free and most popular. The soldan of Egypt, or the emperor of Rome, might drive his harmless subjects, like brute beasts, against their sentiments and inclination: But he must, at least, have led his mamalukes, or prætorian bands, like men, by their opinion.

On the Need for Written Constitutions:

The people, if we trace government to its first origin in the woods and deserts, are the source of all power and jurisdiction, and voluntarily, for the sake of peace and order, abandoned their native liberty and received laws from their equal and companion. The conditions upon which they were willing to submit were either expressed or were so clear and obvious that it might well be esteemed superfluous to express them.

On Mastering Our Passions:

Some people are subject to a certain delicacy of passion, which makes them extremely sensible to all the accidents of life, and gives them a lively joy upon every prosperous event, as well as a piercing grief, when they meet with misfortunes and adversity. Favours and good offices easily engage their friendship; while the smallest injury provokes their resentment. Any honour or mark of distinction elevates them above measure; but they are as sensibly touched with contempt.

Good or ill fortune is very little at our disposal: And when a person, that has this sensibility of temper, meets with any misfortune, his sorrow or resentment takes entire possession of him, and deprives him of all relish in the common occurrences of life; the right enjoyment of which forms the chief part of our happiness.

On the Necessity of a Citizen Militia:

Without a militia, it is in vain to think that any free government will ever have security or stability.

Today, in honor of the birth of this great man, so influential on our Founding Fathers, please go online and read the essay James Madison read and see if you can discover what lead him to choose David Hume as his inspiration that night before the Convention of 1787.