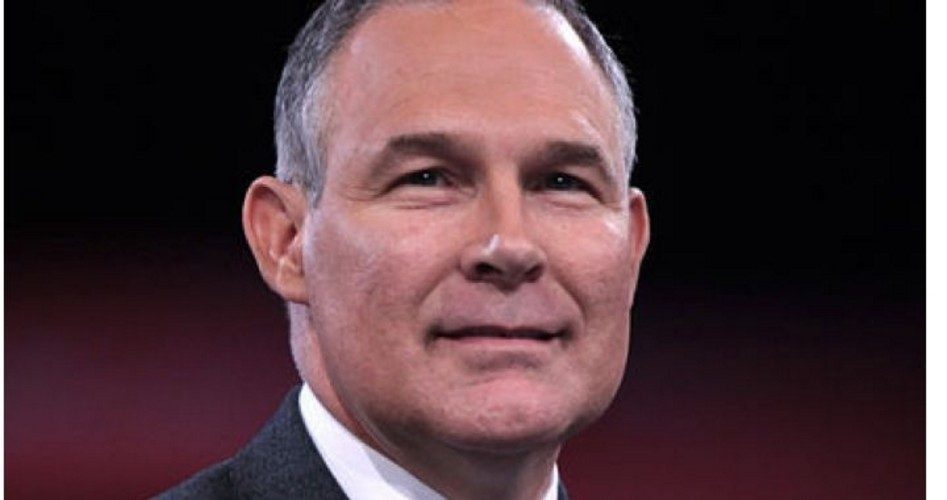

The only type of asset forfeiture that is legitimate is “post-conviction,” Oklahoma Attorney General Scott Pruitt (shown) recently told an interviewer with the CATO Institute. The comments by Pruitt, a Republican first elected in 2010, will assuredly heat up the issue of civil asset forfeiture in Oklahoma.

The decision of Oklahoma County District Attorney David Prater, a Democrat, to send negative information about Senator Kyle Loveless, an Oklahoma City Republican, to the media, will also add to the intensity of the debate. Loveless is the principal proponent of reforming the laws in Oklahoma on civil asset forfeiture.

Under civil asset forfeiture, a law-enforcement officer may seize assets from individuals whom they believe are involved in criminal activity — usually the drug trade. In criminal asset forfeiture, a person’s property cannot be kept by the government unless the person is actually convicted of a crime. Under civil asset forfeiture, however, no conviction and no charges are required, because it is the property — such as cash, a car, or a house — that is being charged, not a person with constitutionally protected rights. This has led to odd-sounding court cases such as The State vs. $12,000 cash, or The State vs. a 2014 Toyota Camry. Loveless wrote a bill that would restrict the authority of police or other law-enforcement officers from seizing and keeping assets before conviction of the person.

Prater, like almost all prosecutors, opposes any significant changes in the law, specifically telling Loveless in an e-mail, “Unless you are willing to remove that mandate [to require criminal conviction to obtain the forfeiture of property] from your proposed legislation, there really is no need to discuss further.”

The typical disagreement between prosecutors and those legislators who try to protect citizens from government is what makes the position of the state’s attorney general to oppose civil asset forfeiture so important: Oklahoma’s highest-ranking prosecutor favors change to civil asset forfeiture.

In the podcast with CATO, Pruitt called asset forfeiture “meaningful [if] rightly used.” He noted that Oklahoma is the home of the crossroads of two of America’s most significant interstate highways (I-40/I-240 and I-35), which intersect in Oklahoma City, and are thus the site of a “significant amount of activity” in the drug trade. He said he had no problem with seizing automobiles, for example, that are used in that trade, but insisted that a person should have to be convicted before a permanent asset forfeiture could take place. “The system we have in Oklahoma is wrong and flawed,” he declared.

Pruitt cited “two egregious examples in Oklahoma” in just the past six months. In one case, a Kansas resident traveling with a contemporary Christian band, who had raised a large amount of charity money to send to Burma, was stopped by the sheriff’s office in Muskogee County for a broken taillight. Since the man was carrying $53,000 in cash, the sheriff’s office presumed it was drug money. They called in a drug dog, who alerted that drugs were in the vehicle. Pruitt told CATO that the use of drug dogs “can be manipulated.”

After four hours of interrogation, the man was released. But the sheriff kept the money — under civil asset forfeiture.

Another example Pruitt offered as an abuse that can occur under civil asset forfeiture was a case in Wagoner County, Oklahoma in which the sheriff conducted a search of a vehicle and simply pocketed the $10,000 he found in it. He is now facing three felony counts.

The only type of asset forfeiture that is legitimate is “post-conviction,” Pruitt asserted, noting that there is “nothing in the statutes now” that even require charges be brought before assets can be seized and kept. One exception that Pruitt gave to a requirement of criminal conviction would be in the case of “abandoned property.” He explained that many times an asset is seized, and the accused person simply abandons the cash, the car, or other types of property and leaves the jurisdiction. Closely related to this exception would be if the person died, was deported, or was an informant to a larger illegal activity and was not charged (although guilty) in exchange for assisting law enforcement in nabbing higher-ups).

Some of the reforms suggested by Pruitt include a “habeas process,” meaning that if the government fails to file charges within a certain time period — he mentioned 60-90 days — “then the person gets their property back.”

He also stated that the focus on the asset forfeiture should be to hold property “in escrow until trial.”

In the past legislative session, Oklahoma made a small step toward reform when Governor Mary Fallin signed legislation that would require the state to pay attorney fees to those whose assets were unjustly seized. The stated need for this legislation was that oftentimes lawyer’s fees are greater than the value of the assets seized.

Even with the support of Oklahoma’s attorney general, making substantive changes to the state’s civil asset forfeiture laws (which are typical of those in most other states) will be a challenge. Those calling for reform can be expected to be accused by district attorneys, sheriffs, and the like as being “pro drug dealer.”

In the case of Senator Loveless, Oklahoma County District Attorney David Prater has demonstrated that he is even willing to attack personally in the press a legislator who attempts to make significant changes.

As part of Loveless’ research on the use of civil asset forfeiture in combatting the drug trade, Loveless asked Prater if he could “ride along and tour” their drug interdiction unit. Loveless told The New American, “I wanted to see how forfeiture was hitting drug cartels.” According to Loveless, Prater asked for some dates, and Loveless suggested the last week of August and the first week of September.

As the time drew near, Loveless sent Prater an e-mail, pointing out that Attorney General Scott Pruitt had come out for even stronger reforms than Loveless had been advocating. “I thought it important that we now have a prominent ally in this effort,” Loveless told us.

Prater responded to the e-mail by informing Loveless that he had done a background check on him, and that “this routine check resulted in the discovery of issues that make you ineligible to tour the COMIT facility or ride with our officers.” Prater cited the fact that Loveless had once had his driver’s license suspended, that he had been ticketed for driving 20-25 miles per hour over the speed limit, and that a portion of his state Senate salary had been garnished as a result of a “judgment” against him.

Loveless admitted that he had received a speeding ticket that went to warrant, but explained that that piece of mail was not forwarded from his previous residence. He added that once he was made aware of the ticket, he paid it.

According to Loveless, not one of those issues was raised in the past, when he had ridden with police. What was important about this e-mail, however, is that Prater also sent a copy of the e-mail detailing all of this to every Oklahoma TV station, as well as the state’s two largest newspapers, the Oklahoman and Tulsa World. This strongly suggests that Prater is trying to send a message to anyone who makes an effort to change the state’s laws on asset forfeiture.

Prater did tell Loveless that he would contact Pruitt’s office “to determine what his position is on this issue.” But Prater added,

Notwithstanding his position, a conviction requirement [before assets could be seized and kept] makes your proposed legislation untenable to me. The Oklahoma District Attorney’s Association has developed proposed statutory changes to the civil asset forfeiture provisions in our laws that address concerns voiced by those advocating ‘reform’ to the process. Purposefully omitted from those proposals is any reference to a required criminal conviction. Unless you are willing to remove that mandate from your proposed legislation, there really is no need to discuss further.

It is unknown what DA David Prater would say if presented the words of the U.S. Constitution’s Fifth Amendment, which reads in part, “No person … shall be deprived of life, liberty or property without due process of law.” (Emphasis added.) But this principle is not unique to the U.S. Constitution. The 1215 Magna Carta, the Great Charter of English liberties, declared, “No free man shall be seized, or imprisoned, or stripped of his rights or possessions … except by the lawful judgment of his equals.” (Emphasis added.) Skipping ahead nearly 500 years, the English Bill of Rights of 1689 presented similar sentiments, when it stated that there should be no forfeiture of one’s possessions “before conviction.” (Emphasis added.)

Western jurisprudence, at first (and second) glance, appears to be in contradiction with the Prater standard, contending that no criminal conviction should be required before the government can seize your private property.

With Oklahoma’s attorney general weighing on the side of the protection of private property rights, perhaps some changes in civil asset forfeiture laws are on the way in Oklahoma — and hopefully the rest of the states.

Photo of Oklahoma Attorney General Scott Pruitt: Gage Skidmore