The Chicago Tribune, in examining more than 67,000 criminal charges between 2012 and 2016, discovered that although bonds demanded by judges in Cook County have doubled for violent crime, the suspects are being freed twice as fast. Wrote the Tribune on Friday:

Since 2012, the median amount of bond set by Cook County judges for people charged with felony gun crimes has doubled – from $25,000 to $50,000.

But over the same time period, the average number of days a defendant spends in jail before posting bond for a gun charge has fallen by more than half, from 42 to 18 days, according to the Tribune analysis.

This is counterintuitive. Higher bonds should keep suspected criminals in jail longer, keeping them off the streets longer, which should reduce crime. But as nearly every observer knows, last year violent crime in Chicago set ghastly records in the number of people being shot and killed.

The Tribune tried to explain it away by referring indirectly to the “Ferguson effect”: “The Chicago Police Department is making fewer gun arrests.… The number of arrests dropped by nearly 9 percent” from 2012 through 2016. This is ascribed to officer reluctance to stop a citizen observed to be engaging in certain behaviors, and a consequent drop in the number of “stop and frisks” as a result. This drop in police proactivity has created a vacuum that the criminal element has been only too happy to fill: lower enforcement leading to more criminal behavior.

The Tribune says that because there are fewer arrests of gang members, the higher bonds aren’t a deterrent. With fewer demands on the gangs’ cash flow, bonding out suspects more quickly is the result. The Tribune describes it this way:

Gang leaders who control drug profits have fewer demands on their money because fewer of their foot soldiers are being locked up thanks to less interference from police in the drug trade.

Part of the “less interference” by the police, as stated above, the “revolving” door police officers are experiencing: A suspect is arrested by an officer at increasingly greater risk of bodily injury or death to the oficer, with the officer learning later that the suspect is back on the street, having been bonded out by his gang. This is hardly encouraging to the officer.

Chicago Police Superintendent Eddie Johnson sees what is happening:

A lot of the shootings occur by repeat gun offenders, which are with the gangs. So when those guys get picked up, for whatever reason, who do you think the gangs are going to bail out first? They bail out the shooters because they are the most valuable pieces to that gang organization….

So what we see is just an unbelievable cycle of CPD arresting these guys, and then … the judicial system spits them right back out, only to be dealt with … again.

There’s another factor that the Tribune failed to cover: the ACLU agreement that is interfering with and slowing down legitimate police work. Although the details of that agreement struck with the CPD in 2015 aren’t public, one can surmise from reviewing the ACLU’s March 2015 study “Stop and Frisk in Chicago.” Its bias is evident in the study’s second paragraph. It is addressed not to the CPD but to the very criminals the CPD is facing down every day:

Under the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Terry v. Ohio … officers are allowed to stop you if the officer has reasonable suspicion that you have been, are, or are about to be engaged in criminal activity. Once you are stopped, if an officer has reasonable suspicion that you are dangerous and have a weapon, the officer can frisk you, including ordering you to put your hands on a wall or car, and running his or her hands over your body.

This experience is often invasive, humiliating and disturbing.

And just how does the ACLU suggest that this experience be limited? By limiting the officers:

In order to restore community trust, the City should make the following policy choices:

Collect data on frisks and make it public….

Collect data on all stops and make it public….

Require officers to issue a receipt.

The data thus collected can be not only perused by the public but also can be used to rate officers’ performance. What officer is likely to welcome such an intrusion during a stop or a stop and frisk that could turn ugly instantly? Especially if he knows that if he makes an arrest, the suspect will be shortly be back on the street?

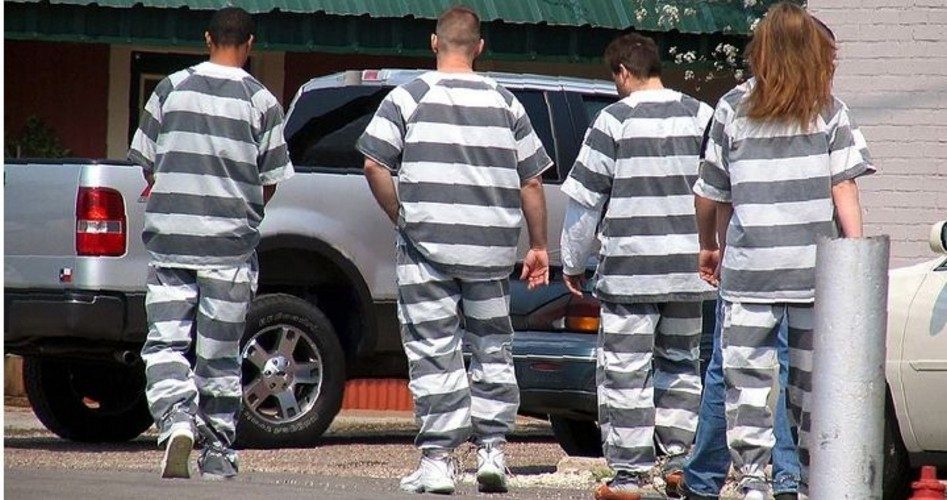

Here’s the cycle that all but guarantees that gun violence in Chicago is going to escalate: Suspect observed, officer judges behavior to be potentially dangerous, a stop and frisk is initiated, leading to an arrest. The suspect appears before a judge who sets bond at $50,000. The suspect is bonded out in a couple of weeks and is back on the street.

In the meantime the officer must, thanks to the ACLU agreement with his department, record every detail of the incident, subjecting himself and his performance to public review and comment as well as providing potential cause for sanction or perhaps even dismissal from the force. Within weeks he observes the suspect back out on the street. Wash, rinse, repeat.

What is interesting is that, prior to August 7, 2015, when the CPD agreed to the limits demanded by the ACLU, the annual murder rate in Chicago averaged 458 over the previous six years. In 2016, the first full year following the implementation of that agreement, the murder total in Chicago jumped to 762, an increase of 66 percent.

An Ivy League graduate and former investment advisor, Bob is a regular contributor to The New American magazine and blogs frequently at LightFromTheRight.com, primarily on economics and politics. He can be reached at badelmann@thenewamerican.com.