At first light on April 19, 1775, the soft soil of a village green in Lexington, Massachusetts, was soaked in the blood of farmers, fathers, and freemen. These men — ordinary in station, but extraordinary in spirit — stood shoulder to shoulder, not to revolt, but to defend what was already theirs: the right to govern themselves, to keep what they earned, and to live without the yoke of distant despotism. Their stand that morning, and the ferocious fight that followed along the road to Concord, did not arise in a vacuum. These were not rebels. These were resolute citizens who believed, as John Adams said, that “Liberty must at all hazards be supported.”

What began on Lexington Green and exploded at Concord Bridge was not simply a skirmish between colonial irregulars and Redcoats. It was the bursting forth of a principle long festering in the hearts of British Americans — a principle rooted in the Magna Carta, refined in the English Civil Wars, and now reborn in New England muskets.

Let us recall the precise cause of the conflict: General Thomas Gage, military governor of Massachusetts and agent of the Crown, had ordered his men to march to Concord to seize and destroy colonial munitions. This act, this audacious infringement, was not merely an affront to private property; it was a direct assault on the right to keep and bear arms — a right the colonists understood not as a privilege doled out by Parliament, but as a God-given guarantee essential to the preservation of liberty.

And so, when Paul Revere and William Dawes rode through the countryside that fateful night, they were not crying out for rebellion. They were ringing the bell of duty — calling on the citizens to rise and defend the sacred soil of their homes, their rights, and their posterity.

Lexington: The First Stand

The air on Lexington Green was chilled by spring dew and the breath of anxious men. Captain John Parker, a veteran of earlier wars, gathered his militiamen, knowing full well the odds. “Stand your ground,” he ordered, “Don’t fire unless fired upon, but if they mean to have a war, let it begin here.”

And begin it did.

No man knows who fired the first shot. Some say it was accidental; others claim it was intentional. What is certain is that, within minutes, eight Americans lay dead and ten more wounded. None of them had fired a single shot in return.

These men were not soldiers in the European sense. They wore no uniforms, received no pay, and had no ambition for conquest. They were farmers, blacksmiths, schoolteachers, and shopkeepers. But they were also men who had read their Bibles and their Blackstone, and who had been taught that tyranny, whether by king or by congress, was to be resisted with all vigor and virtue.

Concord: The Counterblow

If Lexington was a tragedy, Concord was a turning point.

As British forces marched on toward their objective, a storm was brewing behind them. The countryside had awakened. The alarm had reached the farms, fields, and villages. Militiamen — Minutemen — were pouring toward Concord like streams feeding a mighty river.

At the North Bridge, colonial militia assembled under the command of Major John Buttrick. When the British fired first, Buttrick cried, “Fire, fellow soldiers, for God’s sake, fire!” The American volley that followed was not simply a response to a military provocation — it was a declaration, a defiant stand that would reverberate across the globe.

It was here that the British were first turned back. Here that the myth of Redcoat invincibility was shattered. Here that the cause of American independence found its first triumph.

As the British began their retreat, the countryside erupted into righteous fury. Every rock wall and tree became a redoubt. The colonists harassed the retreating soldiers with relentless, disciplined fury — an organic, spontaneous outpouring of resistance that no British general had anticipated.

The Spirit Behind the Steel

What makes these battles more than mere military history is the spirit that animated the resistance.

These men were not driven by bloodlust or ambition. They did not desire war. In fact, many still hoped for reconciliation. But they had read the works of Algernon Sidney and John Locke. They knew that liberty once surrendered is rarely reclaimed without sacrifice.

They also knew that arms in the hands of the people were not merely tools of defense, but symbols of sovereignty. They knew that the right to bear arms was a check against tyranny. Gage’s orders to confiscate their weapons was not a defensive act by the Crown — it was the first move in a campaign of subjugation.

Let us be clear: The British march on Concord was not about crime control or keeping the peace. It was a strategic move to disarm a population known to cherish its freedom more than its comfort. The colonists understood that without arms, resistance was impossible. And without resistance, tyranny was inevitable.

Lessons for Our Time

Today, many look back on Lexington and Concord with a kind of detached reverence, failing to see their relevance. But the parallels between then and now are too sharp to ignore.

Then, as now, there were those in power who sought to restrict access to arms under the guise of order and safety. Then, as now, the ruling elite viewed the people’s insistence on rights as dangerous and disruptive. Then, as now, there was a struggle between central authority and local autonomy.

The Minutemen of 1775 understood something we must reclaim: Self-government begins with self-defense. A people incapable of defending their homes are a people already conquered in spirit. The natural right to keep and bear arms is the cornerstone of all other rights.

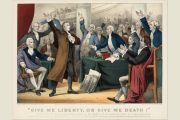

Patrick Henry once asked, “Shall we acquire the means of effectual resistance by lying supinely on our backs and hugging the delusive phantom of hope?” The men of Lexington and Concord answered with their lives. Will we?

Blood as Seed

The blood shed on Lexington Green and at Concord Bridge was not spilled in vain. It was seed — watered by tears, nourished by sacrifice, and quickened by the Spirit of liberty.

From those first fallen patriots grew a tree of liberty whose roots would spread across continents. It bore fruit in the Declaration of Independence, in the Constitution, and in every soul that dared to say: “We will be free.”

We owe them more than remembrance. We owe them emulation.

The Power of Local Resistance

What Lexington and Concord demonstrate so clearly is the power of local action. The resistance to tyranny did not begin with a vote in Philadelphia. It began with town meetings, local militias, and watchful citizens. It began when free people stopped waiting for permission and started acting on principle.

The colonists didn’t wait for a central authority to defend their rights. They took the initiative. They organized. They trained. They acted.

This is the essence of federalism rightly understood: that the real power lies with the people and their communities, not with a far-off capital. It is the states, and ultimately the counties and towns, that must guard the flame of freedom.

Let Us Be Found Worthy

In these days of creeping centralization and concerted campaigns to disarm and demoralize the American people, we must ask ourselves: Are we the heirs of Lexington and Concord? Or are we content to be subjects — pacified, pliable, and powerless?

Let us be found worthy of those who fell on April 19, 1775.

Let us stand, as they did, “between us and our oppressors,” as the Reverend Jonas Clarke put it, and show the world that liberty still has its guardians.

Let us remember that tyranny does not always wear a red coat or march in formation. It can come wrapped in good intentions and “common sense” regulations. It can be masked as safety, compassion, or even democracy. But the price is always the same: your liberty.

And the response must always be the same: resistance.

A Charge to Keep

The men who died at Lexington and Concord did not know they were launching a revolution. They only knew that they had a duty to God, to their families, and to their rights.

Their courage should not be domesticated by distance or dulled by ceremony. It should burn in us. It should move us to action — to teach, to speak, to stand, and, if necessary, to fight.

The shot heard ‘round the world still echoes.

The question is — do we hear it?

And if we do, what will we do in reply?

Let us answer as they did — not with hesitation, not with fear, but with conviction born of principle and courage born of duty.

For if liberty is to survive, it must be defended not just by historians and orators, but by citizens.

Armed in knowledge. Armed in faith. Armed, if need be, in the old-fashioned way.