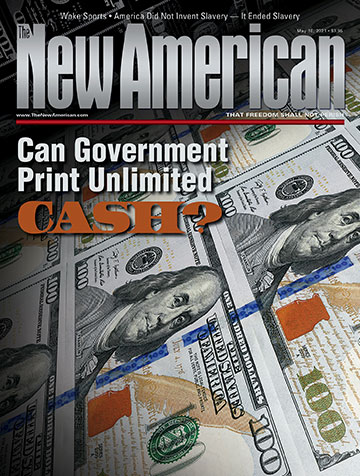

Can Government Print Unlimited Cash?

Recently President Biden unveiled his latest spending initiative, a $2 trillion infrastructure spending plan chock-full of longtime wish-list items of the Left, including massive spending to “electrify” the entire federal vehicle fleet and a large proportion of the nation’s school buses, steps to reduce carbon emissions, and the creation of a “Civilian Climate Corps.” Ostensibly, this is just another big spending cure-all in the grand tradition of FDR, LBJ, Clinton, and Obama, to be paid for by tax hikes and other impositions on big corporations — measures that supposedly will pay for the plan over the next 10 years or so.

In reality, of course, every clear-headed American knows exactly what will happen: Any additional revenues garnered by this latest round of tax hikes on America’s most productive will be squandered by the federal government, as estimates for all of Biden’s new pie-in-the-sky proposals suffer from the usual inefficiencies and unanticipated cost overruns. In the end, the Biden infrastructure boondoggle will simply pile a couple of trillion more dollars onto the national debt, and the usual hand-wringing over the need to impose yet more taxes and create more “stimulus” programs will commence anew. We’ve seen this same show so many times that the predictability borders on cliché. Yet we are fast approaching a point of fiscal and financial no return, a day of reckoning when we are forced to pay the price for decades of irresponsible spending, borrowing, and printing money.

At the time of this writing, the official national debt of the United States stands well in excess of $28 trillion, with an additional million accruing every minute or so. Divvied up among all U.S. taxpayers, the debt amounts to a staggering $224,000 per person. At the same time, the gross domestic product barely surpasses $21 trillion, while the average personal debt per citizen stands at $64,000. These figures tell an increasingly ominous tale, yet, immersed as America has become in the mounting rivalry with Communist China, the stubborn coronavirus pandemic, and the increasingly acrimonious social, political, and cultural divide among Americans themselves, concerns about the skyrocketing national debt have been largely set aside. Some in government and the academy — the devotees of a new economic doctrine called “modern monetary theory” — now assure us that government debt is not the apocalyptic crisis we once thought, and that there is no cause for alarm.

But the verdict of history tells a different story. While wars, pandemics, and societal breakdown may wreak devastation, debt and the economic and financial collapse it eventually triggers can be even more powerful, albeit less understood, “destroyers of worlds.” After all, before World War II, before the Holocaust, before the rise of Hitler, and before the Great Depression, the German economy and society were left in ruins — not so much by the guns of World War I, but by the hyperinflation that followed, an event that wiped out the savings of millions of thrifty, hardworking Germans almost overnight. This event not only impoverished the once-proud nation, it also destroyed every vestige of trust between citizen and state, between banker and depositor, and between creditor and debtor. The resulting societal breakdown was exploited by Hitler and the Nazis. Exhausted and shattered morally and socially, the Germans were in no condition to resist the imposition of Nazism and the catastrophe that ensued.

The German cautionary tale is but one of many; modern history is full of instances of once-vibrant countries being destroyed by economic collapse, from Argentina and Venezuela to Russia and Zimbabwe. We must not let such a disaster overtake the United States — but time is running out to turn the economic and financial tide.

Throughout its relatively short history, America’s debt has risen and fallen. On one occasion, it was even — for a single year, from 1835 to 1836 — completely paid off. America began her life as an independent nation deeply enmired in wartime debt and a monetary crisis that would haunt her for decades. During the Civil War and both World Wars, the federal government borrowed massive amounts of money to cover huge military expenditures. The level of national debt has also fluctuated according to the ebb and flow of the economy, with periodic panics, recessions, and depressions generally driving the debt upward, while periods of economic expansion — until recently — generally allowed the debt to be paid down. But throughout much of this period, it has generally been accepted that debt is at best a necessary evil, and that the proper response to debt is to pay it off. “I go on the principle that a public debt is a public curse, and in a Republican Government, a greater [curse] than any other,” remarked James Madison. His colleague and close friend Thomas Jefferson concurred, saying, “We must not let our rulers load us with perpetual debt.”

Yet perpetual debt is precisely what Americans have been given, along with, in recent decades, an alarming rise in popularity of an old heresy in new garb, the idea that government debt is somehow different from private debt, and that, properly allocated, it will improve national economic health, no matter how high it is allowed to rise.

Recently, this way of thinking has found expression in a faddish new brand of economics misnamed Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). Growing in popularity since the mid-1990s, when it was first articulated by Warren Mosler, MMT has become something of a buzzword in Washington corridors of power thanks to a number of high-profile Democrats, such as Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.), who have openly embraced and promoted it. In essence, MMT makes the reassuring claim that government spending levels are not limited in any way by tax revenues. In the MMT version of things, a sovereign government can create and spend as much money as needed, as long as all sovereign debts are denominated in its own currency. Federal borrowing therefore only constrains interest rates, while taxation is useful only as a tool to curb inflation, by removing money from circulation. Governments must then use money creation as a continuous source of economic stimulus, imposing or hiking taxes whenever inflation threatens to get out of hand.

Unfortunately, its hipness and superficial appeal aside, MMT is but the latest in a very long series of economic half-truths whose deep-seated allure arises ultimately from the very human impulse to try to get something for nothing. Money, MMT theorists argue, has always been a creation of government; even when money was commodity-based (e.g., based on gold or silver), its value and standard units were created by government. Absent laws defining weights, measures, monetary units, accountancy standards, and the like, money simply has no meaning, according to MMT. It follows then that money is the tool, and not the master, of its creator — hence the need for sovereign debt to be denominated always in the sovereign’s own currency.

Modern fiat (unbacked) money, of course, is no longer restrained by a supply of some convertible commodity such as gold or silver; it is undeniably true that governments can create as much money as they like, regardless of how much gold or silver is held in treasury vaults.

However, it is not the case that money originates with government. In the ancient world, money was synonymous with weights (which is why many modern monetary units, such as the pound, the peso, and the lira, all referred originally to units of weight). Units of weight were defined by the state, but only to establish uniform standards of exchange. The money itself was typically a standard amount of gold, silver, or copper reckoned in “grains,” minuscule weights derived from the weight of a single grain of some commodity such as wheat. The idea of coinage was a much later invention, attributed to the Lydians, from where it spread to ancient Greece, across the Middle East to India, and elsewhere. But notice that the original constituents of money — precious metals, grains of foodstuffs such as wheat and beans, and, in some places, cowrie shells, gems, and other commodities — were, then as now, acquired primarily by private enterprise.

On the other hand, modern fiat money is created by government, and, in addition to old-fashioned tax revenue, is used to finance all types of government spending. Indeed, the political appeal of fiat money is that it allows government to spend far more money than up-front taxation would permit. But that does not mean that fiat money has some strange power to conjure wealth out of thin air that old-fashioned commodity money somehow did not have.

Supporters of fiat currency rely for their arguments on a subtle confusion of wealth with money. If it were possible to become wealthy merely by creating money and making sure that all debts are denominated in your own currency, then all of the old-fashioned virtues once believed to be the basis for wealth and success — thrift, delaying gratification, savings, and the like — are shown to be wrongheaded. Indeed, in the modern fiat money-based economy, such virtues are commonly derided. Instead of fuddy-duddy savings and thrift, big spending and borrowing are lauded because such activities allegedly drive the economy.

The problem of debt is not confined to the federal government; America at every level, down to household budgets, is in debt up to its collective eyeballs. Long gone are the days when the average individual would pay off college loans within 10 years, and the average couple would burn the mortgage on their house by their early 40s. Most Americans today seem content to live their entire lives in debt, enticed into such a state by a combination of skyrocketing costs for the things upon which our standard of living most crucially depends — education, motor vehicles, and houses — and artificially low interest rates that make decades-long loans and mortgages seem more palatable. But the stark reality is this: Most Americans will be making mortgage payments their entire lives, and increasing numbers of people are entering their 60s with student-loan debt still unpaid. The old-fashioned American dream of a secure retirement and financial independence by middle age appears to have gone the way of Burma-Shave signs.

Nor is this merely a cultural shift. The widespread acceptance of heavy, permanent personal debt is encouraged by the Powers That Be, because the entire viability of modern fiat monetary systems depends upon debt. This is because, strictly speaking, government and banks do not simply “print” money and dole it out like free samples at a grocery store. It is in fact “injected” into the economy using the issuance of debt as a cover. Only the demand for debt creates financial circumstances wherein new money can be issued in response to interest-rate adjustments, bank lending, and government-mandated changes in bank reserve requirements. In other words, if there were no demand for debt, it would be impossible for the fiat money system to work. All of the “money multiplier” models used by bankers and economists to calculate how this or that financial policy action would increase the money supply would be useless if people refused to borrow. Most of the money in circulation would vanish back into bank vaults — as former Federal Reserve Chairman Marriner Eccles once told flabbergasted congressmen — if the demand for debt dried up. And demand for debt would be greatly reduced if more people were willing to save and invest instead of borrow and spend.

The modern monetary system also relies on the ability of governments, working in concert with their respective banking systems, to keep interest rates unnaturally low and terms of payment absurdly lenient, to deceive the public into borrowing amounts that they would otherwise be unwilling to take on. In the world of fiat money, it appears financially advantageous to borrow beyond our means, not only for houses, cars, and education, but also to purchase stocks and bonds and to gamble on foreign exchange rates.

Instead of saving money, most people see no choice but to purchase stocks, bonds, and real estate in the expectation that they will make their money back many times over as markets rise to infinity. Savings and thrift are seen as unwise and passé because inflation tends to erase the value of old-fashioned savings accounts, CDs, and cash over time.

But what is inflation, actually? Few subjects are more misunderstood by the general public, which tends to view inflation as “rising prices.” This mistaken view, shared and promoted by many economists, obscures the true nature and origin of inflation. First of all, rising prices are the effect of inflation, not inflation itself, which is simply an expansion of the money supply via money creation, resulting in diminishing purchasing power of the money already in circulation. Moreover, the rising prices associated with inflation are general, not local, nor are they confined to a few select goods and services. It is incorrect to refer to sudden increases in prices after a natural disaster as “inflation”; such shocks are always temporary and limited to geographical areas affected by hurricanes, earthquakes, and the like. Inflationary price rises occur across the entire country, and affect all goods and services to varying degrees. The cause of such general rises in pricing is government, and the mechanism is the creation of new money by Treasury departments in combination with the banking system. As we have seen, this new money is primarily introduced into the economy by new debt. So an inflationary economy creates a vicious cycle by continually devaluing the currency. A currency that continually loses value disincentivizes saving, and incentivizes borrowing and risky investments. More borrowing creates a need for more debt, which in turn leads to more inflation.

What about the claim made by MMT advocates (as well as Keynesians) to the effect that government debt is somehow different because it can be repaid via monetization (printing currency)? The fatal fallacy with such arguments is that even governments cannot compel others to purchase their debt. In other words, governments are limited in their power to issue debt by the willingness of would-be creditors to loan money to them. Many governments that develop reputations for profligacy and even default often find it impossible to borrow because no one is willing to lend to them — or will only loan money with very high interest and stringent repayment conditions. This has been the case now for many years with Argentina, for example, which has defaulted several times on debt in the last several decades, each time bitterly blaming wicked foreign capitalists for all of their woes. During the European financial crisis a decade ago, several EU states, most notably Italy, faced the unpleasant reality of having to borrow money at higher interest rates than they wanted because of widespread perception among creditors that their economic and financial condition was a very risky lending environment.

The United States, on the other hand, never seems to encounter the same problems with creditors as faced by the likes of Argentina. No matter how much new money is created by the Fed, and no matter how high America’s debt climbs, hyperinflation, collapse of the dollar, and other long-forecast events remain illusory. In particular, the massive inflation and consequent dollar crisis predicted by many economists as a result of years of massive money creation in response to the Great Recession of 2008 seemingly never came to pass. But appearances are deceptive, as Peter Schiff, an outspoken foe of MMT and fiat money, explained in Reason magazine:

Broader consumer price inflation has been kept at bay because many of the newly printed dollars don’t even hit our economy. Instead, foreign countries purchase them in an attempt to keep their own currencies from appreciating against the dollar. In the current environment, a weak currency is widely (and wrongly) seen as essential to economic growth. That’s because a weak currency lowers the relative price of a particular country’s manufactured goods on overseas markets. Nations hope those lower prices will lead to greater exports and more domestic jobs.

Thus we see “currency wars,” in which the victors are those who most successfully debase their currencies. That policy perpetuates greater global imbalances (between those nations that borrow and those nations that lend) and the accumulation of dollar-based assets in the accounts of foreign central banks.

The more debt the U.S. government issues, the more purchases these foreign banks must make to keep their currencies from becoming more valuable relative to ours. It is no coincidence that many of the countries heavily buying U.S. dollars, such as China, the Philippines, and Indonesia, are experiencing high levels of domestic inflation. Inflation may now be America’s leading export.

In other words, the United States can get away with massive inflation because it is able to export dollars. Countries such as China snap up excess dollars to ensure that their dollar-denominated assets (including debts owed by the United States to them) do not lose value. But this prompts another question: Why are foreign countries so eager to maintain a strong dollar, and willing to hold assets denominated in dollars? The answer has its roots in the Bretton-Woods Conference held in 1944, in which the United States dollar was set up to be the world’s reserve currency, meaning that international transactions were ultimately to be reckoned in dollars. Originally, the United States agreed to keep the dollar tethered to a gold standard for the sake of international holders of dollars — although American citizens were no longer permitted to own monetary gold or to redeem dollars for gold. This “gold window” was repudiated by President Nixon, to the consternation of foreign holders of American dollars, and resulted in a “dollar shock” that reverberated throughout the 1970s, creating recession and stagflation. In the end, though, the global economy recalibrated to the reality of a fully fiat American dollar, which has remained the world’s reserve currency to this day. In other words, if other countries wish to be part of international finance and trade, they are currently forced to accept the dollar’s reserve status. This means, in effect, that the United States enjoys tremendous (and unjust) leverage over the rest of the world’s currencies, as well as a convenient inflationary safety valve not enjoyed by the likes of Argentina or Zimbabwe.

Rise of radicalism: Never before has the federal government been so dominated by the radical Left, whose stated aim is to tear down the Republic and Constitution and replace them with Marxism. Can the Republic survive the relentless attacks led by the likes of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez? (Photo credit: AP Images)

But the effects of the massive inflation are still visible in the U.S. economy — years of “quantitative easing” (printing money and using that new money to buy government and private stocks and bonds) on the part of the Fed have resulted in spectacular run-ups in asset pricing, such as the stock market. As Schiff observed in 2014, well before the Trump presidency:

Through its zero-interest-rate policy and direct asset purchases via quantitative easing, the Fed has lowered the cost of capital and raised prices for stocks, bonds, and real estate….

Over the past five years, the prices of these financial assets have risen dramatically. However, unlike past periods of bull asset markets, these increases have not been accompanied by robust economic growth. To the contrary, the last five years have seen the slowest non-recession economic growth since the Great Depression.

This Fed-driven dynamic explains the rich-get-richer economy we’ve seen since the alleged recovery of 2009 began. The wealth effect has allowed the elites to push up prices for high-end consumer goods such as luxury real estate, fine art, wine, and collectible cars. But that is cold comfort to rank-and-file Americans struggling to find work in an otherwise stagnant economy.

In broad outline, then, the system allows the Federal Reserve, together with the Treasury Department and the banking system, to create money practically at will, by the issuance of debt. This state of affairs also keeps interest rates artificially low, discouraging savings and incentivizing borrowing. And the American dollar is shielded to some extent from the effects of consumer price inflation by the demand for dollars overseas — a demand imposed on the rest of the world by the legal status of the U.S. dollar as the world’s sole reserve currency. Under such conditions, it might indeed appear that the U.S. economy is impervious to the sort of debt-related woes that afflict other countries. But no matter how clever the financial gimmickry, no matter how airtight the regulations, no government can compel any other party to accept either its currency or its debt, if push comes to shove. For the past 75 years, the international monetary system has acquired a certain inertia, as the world has adjusted to the reality of the U.S. dollar. Yet old orders can and do change, as circumstances become intolerable. In certain parts of the world, other currencies are beginning to gain favor over the U.S. dollar, especially the Chinese renminbi.

Much of the global perception of the dollar’s invulnerability stems from the overall strength — military, political, and economic — of the United States. But this, too, is looking increasingly fragile in recent years, as witness the epic economic and social unraveling in the United States in 2020, triggered by the coronavirus pandemic and unrelenting hostility of America’s power elites to the Trump administration. The piling on of trillions of dollars in new debt — not to mention massive new taxes and regulations — in response to the pandemic will not pass unnoticed by hard-eyed investors. How can a United States seemingly bent on impoverishing its own citizens, succumbing to lawlessness, and permitting public corruption (including electoral fraud) at Third World levels, be relied upon to continue to service its debts and to be a responsible custodian of the world’s fallback currency? All these are questions that foreign lenders will be asking, more and more stridently, if the United States does not soon correct its path. In the end, such misgivings will give way to a full-blown crisis of confidence in the U.S. dollar and in the entire dollar-based global system. When that unhappy day arrives, the United States will discover that it can no longer issue public debt on its terms and print any quantity of money it deems expedient. Dollars pumped into the economy will no longer slosh overseas; they will remain in American bank accounts, driving up consumer prices and ultimately destroying the value of the dollar as surely as happened in Weimar Germany.

How long it may take for events to reach such a pitch is impossible to predict. Black swan events, such as the ongoing pandemic and its economic and geopolitical fallout, may hasten the process. War is often another catalyst of economic catastrophe. The hyperinflation in Weimar Germany occurred after Germany’s humiliating loss of World War I and war reparations. The aforementioned closure of the “gold window” by Nixon was necessitated by Vietnam War expenses; when the United States withdrew in defeat from Vietnam, the blow to American prestige was considerable, and probably contributed to the stagflation of the ’70s and early ’80s. Argentina’s stunning loss to the British in the Falklands War led to a run of hyperinflation that left the Argentine economy in ruins. For the United States, while the prospect of a ruinous foreign war may seem less likely than in 1940 or 1970, continual domestic unrest, unrestrained illegal immigration, and almost constant political malfeasance are all factors likely to erode confidence, both at home and abroad, in America’s continued viability as the sole economic superpower.

None of these considerations enter into the flawed calculus of MMT or even Keynesianism. All such proponents of debt and fiat currency believe that the system is self-maintaining as long as the proper government regulations are put and kept in place. They fail to understand that no financial system can be made impervious to the choices of consumers. The day that global consumers end their love affair with the American dollar and with dollar-denominated public debt will be a dark day indeed for America.

It’s Not (Yet) Too Late

Can this eventual day of reckoning be avoided? Yes, if Americans are willing to force their leaders to take some politically difficult steps, including curtailing government borrowing, cutting hundreds of billions, if not trillions, of dollars in unnecessary and unconstitutional spending, and ultimately restoring the American dollar to a gold or bimetallic standard. Because all of these steps will of necessity entail some short-term economic pain, and because they will be strenuously resisted and impugned by the Deep State, it will require a tremendous level of national character and endurance to effect what needs to be done. Kicking the can down the road has proven a viable short-term strategy for decades, because the American system is more cleverly insulated than any other against the laws of economics. But in the long run, to paraphrase John Maynard Keynes, we will all be bankrupt, an outcome that will be infinitely worse than any short-term inconveniences arising from a return to fiscal austerity and economic sanity.