How can they think they’re capable of managing a complex health care system, one-seventh of the entire U.S. economy, when they can’t even build a half-decent statue?

That’s the question that came to mind about the bureaucrats, politicians, and central planners in D.C. when I saw that Chinese sculptor Lei Yixin was busy doing major re-carving in order to conceal an incorrect phrase at the $110 million Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial in Washington that he designed. At an estimated additional cost of $700,000 to $900,000, Lei is attempting to cover up a flawed quote by carving horizontal grooves over the words to match existing horizontal striation marks on the memorial’s statue of King.

On the rest of the statue, Lei is working to deepen all grooves so they’ll match the new grooves.

The downside is that the fix might cause cracking. “The difficulty is the new striations — so they won’t damage the integrity of the statue itself,” Lei cautioned. “If it has some cracks, we could deal with them.” Perhaps with another million or so.

The quote elimination and makeover grooves are supposed to be completed by August 28, the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington and the “I Have a Dream” speech King delivered on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial.

The phrase that was supposed to be carved on the statue of King, an exact quotation, came from King’s “Drum Major” speech, delivered in Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta in 1968, two months before he was assassinated.

“Yes, if you want to say that I was a drum major, say that I was a drum major for justice,” said King in that sermon. “Say that I was a drum major for peace. I was a drum major for righteousness. And all of the other shallow things will not matter.”

Because of alleged space limitations — even though the King memorial covers four acres and includes a 450-foot inscription wall for quotes and a 30-foot statue of King — the aforementioned quotation from the Ebenezer Baptist sermon was shortened and paraphrased by the memorial’s designers to simply and incorrectly say “I was a drum major for justice, peace and righteousness.”

Critics argued, correctly, that the revised quote, leaving out “if you want to say that I was a drum major,” made King sound arrogant.

That image of arrogance was tripled or quadrupled by Lei’s Maoist caricature of King.

“Suited and stern” is how the New York Times cultural critic Edward Rothstein described King as portrayed by Lei. “His face is uncompromising, determined, his eyes fixed in the distance.”

Judging the memorial “a failure,” Rothstein saw King’s pose by Lei as “authoritarian,” more like a “warrior or a ruler” than a minister.

Another objection regarding the style of the King memorial, wrote Clarence Page, African-American columnist and editorial writer with the Chicago Tribune, is that the memorial “was designed by a Chinese artist, carved by Chinese workers out of Chinese granite and shipped here and reconstructed by Chinese workers.”

The “stern, crossed-arm stance” that Lei gave King, said Page, is a “demeanor a bit too much of a worker’s paradise seriousness for my taste.”

The artist, “Lei Yixin, a 57-year master sculptor,” stated Page, is “better known for his mammoth tributes to Chairman Mao,” a dictator who unleashed the crimes, terror, repression, and flawed economic model of collectivism and redistribution that caused the death of an estimated 65 million people in China.

Similarly, after pouring $62 million into the now-stalled $142 million Dwight D. Eisenhower Memorial — set to be built near the National Air and Space Museum with a design that has elicited widespread disapproval, including publicly expressed opposition from the Eisenhower family — the Congressional Budget Office estimated that it will cost an additional $17 million to redesign the memorial.

The focal point of the widely disparaged current design shows Eisenhower as a lounging teenager, dreaming about his non-farm future. “The statue is a sentimental piece of kitsch that belongs in a snow-globe,” haughtily declared National Civic Art Society president Justin Shubow.

And, what, we’re supposed to be just fine with the idea that this crowd of credentialed central planners will be setting the price and protocol for intestinal transplants — and deciding who sufficiently fits the grid to become a federally sanctioned recipient?

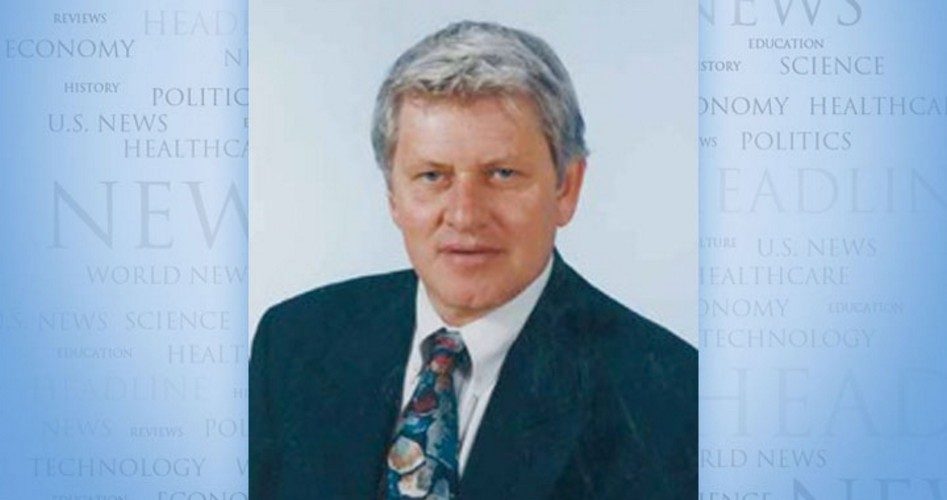

Ralph R. Reiland is an associate professor of economics and the B. Kenneth Simon professor of free enterprise at Robert Morris University in Pittsburgh.