The story line in the new theatrical release Promised Land is obviously intended to leave audiences with a very dim and scary view of fracking and the companies that use this new method of drilling to tap vast amounts of oil and natural gas that otherwise would be inaccessible. But the depiction in Promised Land is so fantastic that the intent could backfire. Indeed, by the end of the film, moviegoers may be left annoyed and offended by the blatant attack on fracking. Indeed, this reviewer was very annoyed. (Warning: spoilers follow.)

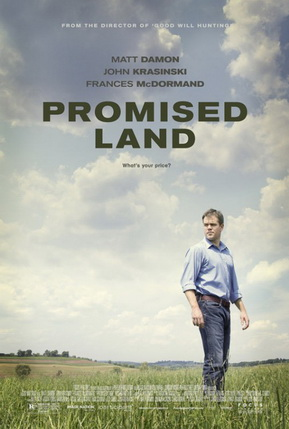

In Promised Land, Steve Butler (Matt Damon) and his associate Sue Thomason (Frances McDormand), representing drilling-giant Global Crossover Solutions, are assigned the task of getting the residents of a small town in rural Pennsylvania to sign leases for drilling on their property. This sets the stage for the inevitable confrontation with an environmentalist, Dustin Noble (John Krasinksi), who thinks Butler is taking the town for a ride.

At first Damon dons the mask of respectability. He expresses his belief that his job is far more than just a job — it’s a passion, a calling. He sees Global’s willingness to offer cash incentives to the town’s residents in exchange for their signatures as “a way out” of their current financial difficulties brought on by the recession. That’s why his success in closing such deals is three times that of his nearest Global associate.

Things go smoothly at first with citizens signing on the dotted line and visions of Global sugar plums dancing in their heads. One of the citizens purchases a high-end sports car and shows it off to Butler in anticipation of riches to come.

But when Butler is about to close the deal in the school’s auditorium with half the town present, the true agenda of the film is exposed. Retired school teacher Frank Yates (Hal Holbrook) begins asking questions that Butler (predictably) cannot answer. You know the drill: Fracking is dangerous; Global is the target of numerous lawsuits (why would that be, if the company is pristine?); peoples’ drinking water is at risk; etc. And how does Butler respond? Well, he lets the charges go unanswered. The implication, of course, is that the charges are true.

Then the concerned and caring environmentalist Dustin Noble (love the name, don’t you?), played by Damon’s co-producer Krasinski, shows up, winning favor during “open mike” night at the local bar, and catching the attention of Butler’s love interest, school teacher Alice (Rosemarie DeWitt). Recognizing the threat to his plans to close the deal with the citizens at the next meeting, Butler’s associate Sue Thomason (Frances McDormand) offers Noble a large envelope of cash to just go away. Noble takes the cash, leaving the audience with the first real distaste of “how business is done” in the drilling business.

Of course, Noble doesn’t go away but in fact continues to have success in awakening the townspeople to the supposed dangers of fracking. In one especially memorable scene, Noble sets up a mock-up model of a farm, complete with barn, horses, cows and chickens, in front of a fourth-grade class. He pours water into a leaky plastic baggie filled with sand and then adds chemicals —suggesting that some of them are secret — and explains that holes drilled into the ground will be filled with this concoction in order to extract the natural gas hidden below.

Then, in a moment of breathtaking audacity, he pulls out a fireplace lighter and sets the entire scene ablaze to the horror of the kids and their teacher.

This whole scene was just too much for the reviewers at Scientific American, who described the surreal scene in detail and noted that the classroom demonstration of the hazards of fracking is “ridiculous” and a “cheap trick”:

Just at the height of the tension between gas guy Steve and enviro hero Dustin, teacher Alice invites Dustin to her classroom. He has built a big model of a farm on Alice’s desk, with a nice farmhouse, green grass, a tractor and cute farm animals grazing about. He says some people want to come [and] drill on that farm. But they don’t use a little drill like your daddy does around the farm, they use a really big drill — and he wields a big spike and starts poking holes in the grass around the farmhouse and animals. He then explains how the company people need to help the drilling by using sand; he holds up a gallon-sized clear-plastic freezer bag with some sand in it. And they don’t just use sand, he tells them, they also use water, lots of water; he drains a plastic water bottle into the sandy bag…. And they also need chemicals; he plops three big bottles of chemicals onto the desk, then dumps them like waterfalls into the bag, which startles the kids. The portrayal is … totally wrong. Although thousands of gallons of chemicals are sent down a fracking well, that’s compared with millions of gallons of water, so the mix in the bag is extremely disproportionate….

[H]ere’s where the real transgression occurs. Dustin says that to get the gas out, the company has to pour the sand, water and chemicals into the holes. So he holds the now busting bag over the farm and pours the nasty mixture all over the grass, the animals, everything, until the toy plot is soaking wet. The kids are aghast.

Yet that’s not all. See, when the chemicals are in the ground they can get into the water, and when that happens — he reaches for an igniter, one of those handheld flints, about the size of a pair of scissors, that go “click-click” to light a barbecue grill…. He touches the igniter to the grass, it goes “click-click,” and phoom! The whole farmstead goes up in flames.

Sorry, movie people, but that’s ridiculous. Contaminating groundwater is a serious issue, and having gas infiltrate drinking water is a serious issue. But a farmhouse’s front yard wouldn’t be soaking in chemicals and it wouldn’t ignite like a fire pit because of fracking. And doing that in front of 10-year-old kids is a cheap trick.

Indeed it is. In real life, anti-fracking environmentalists claim that fracking is responsible for methane getting into groundwater while also pointing out that the contaminated water will burst into a ball of fire when a flame is applied to it. The truth is that methane was found in groundwater long before fracking existed. It got there naturally. There is no evidence that fracking is now causing methane to get into the water supply. For a good article on this subject, this reviewer recommends “Firewater and Other Urban Fracing Legends” by Rebecca Terrell.

Back to the movie: Noble’s stunts against fracking does not end with his classroom demonstration. He also shows the townspeople photos of dead cows that supposedly died as a result of fracking. Butler is put on the defensive. He still has nothing to say in defense of Global, and he once again leaves unanswered the charges against Global in particular and fracking in general.

However, when Butler gets a mysterious package from Global headquarters with proof that Noble’s photos are faked, it’s game over. The town is ready to sign on the dotted line.

But not quite yet. In a final confrontation between Butler and Noble it is learned that Noble is a double agent, working for Global all along, just to make sure that the citizens go along with the scam. Says Noble, “Global covers every angle. They wouldn’t leave anything as important as this to chance.”

In the film’s final scenes, Butler gets the girl (Alice), Noble disappears over the horizon, Sue flies back to Global headquarters, the townspeople are aghast when they learn of the deception pulled on them, and viewers are left with the deliberate impression that no one associated with fracking or the drilling industry —or, for that matter, corporate America itself — can be trusted.

It’s a fine piece of propaganda. It’s not suited for anyone offended by rough language with a well-deserved R rating. And the film took a dismal 10th place in its initial weekend box office, with just $4.3 million in ticket sales.

A graduate of Cornell University and a former investment advisor, Bob is a regular contributor to The New American and blogs frequently at www.LightFromTheRight.com, primarily on economics and politics. He can be reached at [email protected].