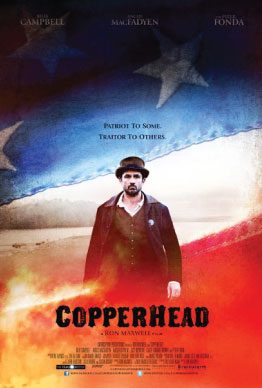

Grand armies with spectacular battle scenes and heroic acts filled the screen in director Ron Maxwell’s epic motion pictures Gettysburg and Gods and Generals, but similar scenes of martial valor are missing from his latest Civil War movie, Copperhead.

Instead, Maxwell explores another aspect of the War Between the States: the impact of the conflict on civilians far from the battlefields. His motion picture centers on a dairy farmer in upstate New York. Abner Beech (played by Billy Campbell, known best for his role in the ABC drama Once and Again) opposes President Lincoln’s invasion of the seceded Southern states, earning him the epithet of “Copperhead” from many of his neighbors, who support the war.

Of course, a copperhead is a venomous snake, and ardent supporters of Lincoln’s war to “save the Union” applied it as an insult on those Northerners, the “peace Democrats,” who opposed Lincoln’s war. Some Copperheads actively encouraged desertion and resistance to the draft, but most, like the movie’s Abner Beech, simply opposed the war through peaceful means, such as stating his opposition publicly and voting for Democrat candidates who would stop the conflict. Even these limited actions were considered unpatriotic, and even treasonous by the war’s supporters.

The movie opens in the spring of 1862, with Beech’s adopted son, Jimmy, lamenting that “the war came home and nothing was ever the same again.” Beech’s natural son, Thomas Jefferson (“Jeff”) Beech, has taken a liking to a young schoolteacher, Esther Hagadorn (performed by Lucy Boynton, who played the young Beatrix Potter in Miss Potter). She reciprocates his affections, but detests his name, Jeff, a given name he shares with the man whom she calls the president of the “Rebellion.” In this, she is parroting the views of her pro-war father, Jee Hagadorn (played by Angus MacFayden, a Scottish actor who performed in Braveheart). At Esther’s urging, young Jeff (or Tom, as he now calls himself to please the pretty Esther) enlists in the Union army.

This greatly distresses Jeff’s father, Abner Beech, who believes his son will be attacking those who had done him “no harm.” A masterful screenplay by writer Bill Kauffman enables Beech to deliver articulate opposition to the war, without subjecting the movie audience to didactic speeches. Beech rails against Lincoln’s multiple violations of the Constitution, including the closing of hundreds of anti-war newspapers and the imprisonment of thousands of war opponents. While he clearly opposes slavery, Beech contends that it is not any of the business of New York State what the South does.

“We don’t want our Constitution dying, and we don’t want our boys dying with it,” Beech declares in one scene. In another part of the movie, his neighbor Avery, played by Peter Fonda, asks Beech, “Doesn’t the Union mean anything to you?” Beech said that, yes, the Union “means something. It means more than something.” But, the Constitution, New York State, his farm, and his own family “mean more.” He adds to Avery, “Even though we disagree, Avery, you mean more to me than the Union.” Even Beech’s minister uses the pulpit to compare Democrat politicians such as former President James Buchanan to the “blasphemous names” on the head of the biblical Great Beast of Revelation. On his way out of the church, Beech asks the preacher if “Blessed are the peace makers” is still in the Bible.

Beech begins to pay a price beyond challenging questions from a neighbor, or unpleasant sermons. Shop owners and others stop buying his milk and his timber, breaking their agreements with him. Beech compares this to the national situation, lamenting that this is what one can expect when you “tear up the Constitution.” If the great national contract is not honored, breach of a simple business contract is not surprising.

Jee Hagadorn takes a contrary view. He is a strong supporter of the war, increasingly so when Lincoln announces the Emancipation Proclamation, which “freed” the slaves in those areas of the country “in rebellion” against the federal government. Hagadorn’s intensity in favor of the war and abolition is such that he refuses to express a shred of concern when his grief-stricken daughter tearfully informs him that her beloved Tom (Jeff) has gone missing in action after the bloody Battle of Antietam. “What should I care?” is his callous response, adding that he would be willing for 10,000 Toms to “perish” if that would end the scourge of slavery.

Hagadorn tells his own son Ni (played by Augustus Prew) that Ni’s refusal to join the Union army has shamed him. Ni responds that he did not know that killing was the Lord’s work, and challenges his father’s comparison of Beech to a snake. “Maybe I don’t share his notions, maybe he’s wrong, but he’s a man, not a snake.” Later, Ni asks what happened to the biblical injunction to “love thy neighbor.”

Beech and his hired hand, Irish immigrant Timothy Joseph Hurley, are forced into a fight with some belligerent pro-war Republicans at a polling place in the 1862 elections, when Hurley attempts to hand in his Democrat ballot. At first Hurley is denied the right to vote, even though he has proper naturalization papers and has been voting since 1852, boasting that he helped put Democrat Franklin Pierce into the White House. After a brief skirmish, both Hurley and Beech vote the Democrat ticket. The outcome of the election gives Beech and Hurley hope, as the Democrat candidate for governor, Horatio Seymour, narrowly defeated his Republican opponent. They hope that the Democrats will win control of Congress and shut the war down, bringing a swift end to the “houses of mourning” across the country.

To celebrate the Democrat victories of 1862, Beech throws a bonfire celebration, which he calls the “Fire of Liberty.” This enrages some of his pro-war neighbors, and moves the picture to its dramatic and surprising conclusion.

In his first two Civil War movies, director Ron Maxwell told The New American, his desire was to examine both the men in blue and in gray “equally” by “looking into their hearts” to see what motivated them. “I got a lot of flak, because some in the mainstream media don’t want to look upon any man who wore a Confederate uniform as a full human being.”

“The first two movies are a cinematic presentation of why good men choose to fight,” while Copperhead is an effort “to explore cinematically, why good and honorable, ethical, moral men choose not to go to war,” Maxwell said. “Not everybody who hated slavery or loved the U.S. Constitution was willing to send their children off to die or be maimed in a bloody battle against fellow Americans. That fascinating reality is the force driving Copperhead.”

The movie is based upon the late-19th-century work of Harold Frederic, who used real-life events he witnessed in upstate New York during the war in crafting his novel, The Copperhead. “I call him [Frederic] the Charles Dickens of upstate New York,” Maxwell explained. “If you want to know about rural America in upstate New York in the 19th century, he’s the guy.”

Maxwell selected Bill Kauffman to write the screenplay. Kauffman’s book Ain’t My America was a history of the anti-war conservative tradition. Kauffman was also the editor of A Story of America First, a memoir of the anti-war America First Committee’s congressional liaison, Ruth Sarles.

Since the ancient Greek playwrights, background music has been a standard part of drama. It is no different in Copperhead, with Laurent Eyquem’s musical score properly creating the somber mood the material dictates, without descending into despair. Eyquem made use of instruments common to the time period, such as the fiddle and the wooden flute, “to tie the score to the historic roots of the story.”

This article is an example of the exclusive content that’s only available by subscribing to our print magazine. Twice a month get in-depth features covering the political gamut: education, candidate profiles, immigration, healthcare, foreign policy, guns, etc. Digital as well as print options are available!

Related article:

Interview With Ron Maxwell on His New Civil War Movie “Copperhead”