Clint Eastwood’s powerful movie illustrates the dangers of Big Government agencies not only unchecked by Big Media, but also when they are in league with each other.

Only a year after the infamous 1995 bombing of the Oklahoma City Alfred P. Murrah Building, the bomb explosion in 1996 at Atlanta’s Centennial Olympic Park understandably created great fear in the general public of continued domestic terrorism, along with a frantic desire to capture the person or persons who could commit such an evil act.

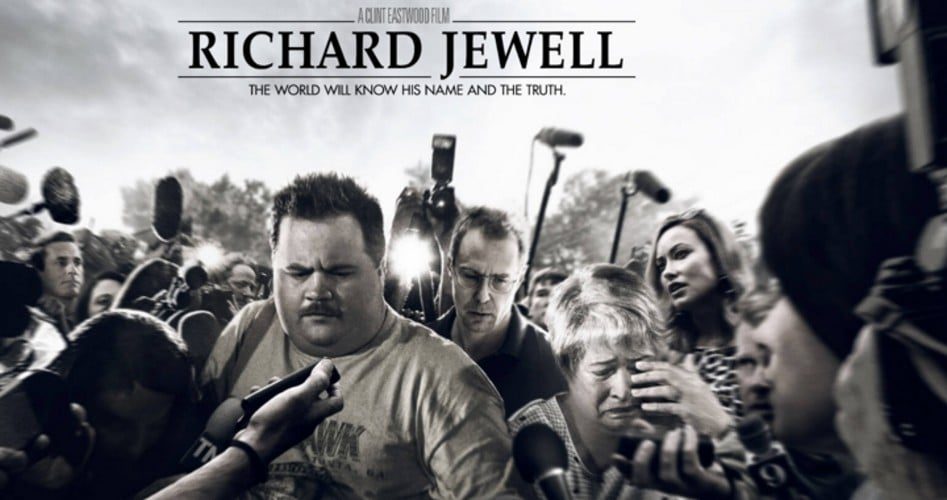

Unfortunately, such zeal can lead to injustice, as director Clint Eastwood’s movie Richard Jewell expertly dramatizes.

Richard Jewell was the security guard falsely accused of placing a bomb in a backpack at Centennial Park during the 1996 Olympics. (The 1996 Olympics was the 100th anniversary of the 1896 restoration of the ancient Greek games). Jewell is now credited with saving hundreds of lives when he discovered the backpack with the bomb. But soon after the explosion, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), intent on capturing the person who planted the bomb, targeted Jewell himself as the suspect, or as they put it, “a person of interest.”

Rather than playing the needed watchdog role of the government, one media outlet after another mostly joined the FBI with multiple stories that Jewell was the likely culprit.

Using the power of the big screen, director Clint Eastwood makes the case that an innocent man can be falsely accused in the atmosphere of fear found in the aftermath of a terrorist attack. Of course, Eastwood does not accomplish this by himself — Paul Walter Hauser turns in a sterling performance as the falsely accused Richard Jewell, while Kathy Bates does likewise in playing Jewell’s mother. (She has earned a nomination for a Golden Globe award.)

The movie takes us back 10 years before the bombing, with Jewell in his position as a clerk for the Small Business Administration. There, Jewell becomes friends with one of the lawyers, Watson Bryant, after Jewell not only keeps Bryant well-stocked with office supplies, but even leaves some Snickers candy bars on the attorney’s desk. (Jewell is observant — he had noted some empty candy wrappers in Bryant’s trash.)

Jewell wants to work as a law-enforcement officer and knows quite a bit about police procedures. Eventually, Jewell fulfills his dream when he takes a job as a deputy sheriff.

Sadly, Jewell loses the deputy’s job, and is shown working as a security officer at a local Baptist college, Piedmont. But he loses that job, too, when some college students complain that he is being too aggressive in his enforcement of campus rules against drinking.

Finally, Jewell is depicted working security at Centennial Park in 1996, living with his mother, after his latest job loss.

Jewell’s work is rather uneventful until he has to confront some drunks breaking bottles behind a tower where cameras are recording an outdoor concert. As Jewell gets the young men to leave, they knock over a backpack, which falls under a bench.

He almost immediately suspects that the backpack contains an explosive, but at first, police officers ridicule his concern. Jewell is persistent, and a bomb specialist is called in, who discovers three pipe bombs are in the backpack. The expert’s face is drawn of color and he tells the other law-enforcement people that it is the largest pipe bomb he had ever seen.

Jewell and other police officers begin clearing the crowd away from the backpack, but before everyone can get away safely, the bombs detonate. One person is killed, and over a hundred more are injured. No doubt, without Jewell’s actions, many more would have died. Before the bomb exploded, he even bravely runs up into the AT&T tower to warn the workers there that they needed to get out immediately

At first, Jewell is hailed as a great hero — a designation that he rejects. But as the FBI puts together its lone-wolf profile (Jewell is a single white male and he owns guns, after all), they remember another bomb case (at the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics) in which the bomber turned out to be the man who supposedly discovered the bomb. Unfortunately, a reporter (played by Olivia Wilde) for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution learns from the lead FBI agent that Jewell has become their most likely suspect.

Fortunately, Jewell’s lawyer friend (played by Sam Rockwell) saves Jewell from being tricked into confessing. FBI agents even tried to convince Jewell to sign a form to waive his constitutionally protected rights with the lie that he was part of a “training film” about bomb detection. Jewell, who has studied police procedures, protests, “This is a real document. I don’t think I would feel comfortable signing something like this.” He then calls his lawyer friend Bryant. Bryant, who earlier in the film had denounced the maltreatment of small business owners by the SBA that he worked for, is a libertarian. No comment is ever made in the film directly about Bryant’s political beliefs, but on his wall are posters of the Bill of Rights and a simple statement: “I fear government more than I fear terrorists.”

Still, Bryant is somewhat reluctant to take the case, until his assistant, Nadya, whose Russian accent indicates she had lived under communism, bluntly tells him, “In the country I come from, if the government says you are guilty, you are actually innocent.”

Bryant asks his client whether he has ever been involved in any anti-government extremist activities, to which Jewell answers no. In fact, one of Jewell’s biggest problems is that he has too much implicit trust in the FBI. When Bryant asks him if he has ever been a member of a religious cult, Jewell responds, “Not unless you consider being a Baptist part of a religious cult.”

Not everyone is pleased with the film, particularly the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. It argues that its role in the affair has been unfairly characterized in the film, particularly the actions of reporter Kathy Scruggs, who, the movie implies, offered sex to the lead FBI agent in exchange for the story.

Eastwood has rejected the newspaper’s objections, accusing them of trying to “rationalize” their portrayal of Jewell in news articles.

Some suspect that Eastwood is making a link to contemporary events involving collusion between the FBI and the left-wing national media. Certainly, neither the FBI nor much of the media come across well in this dramatization of the events of 1996. Obviously, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution was told by someone inside the FBI that Jewell was the most likely culprit, and the newspaper’s reporting (along with other major media outlets) almost railroaded an innocent man. Eventually, the actual culprit is captured and confesses to the crime, but not before much of the public was convinced by the media and the FBI that Richard Jewell was a terrorist.

After days of being overly deferential to the FBI, Richard Jewell finally tells his tormenters, “I used to think federal law enforcement was the highest calling…. I don’t think that anymore.” He then asked them what will the next security guard do the next time he sees a backpack? One could add, or any other private citizen, considering the nightmare that Jewell experienced at the hands of the government agents and the national media.

He also noted the irony of the three words underneath the FBI logo on the door: “Fidelity, Bravery, Integrity.”

This powerfully demonstrates the danger inherent in blindly trusting the media or the FBI. After all, what happened to Richard Jewell could very well happen to anyone else, given the right circumstances.

Photo: richardjewellmovie.com/

Steve Byas is a university instructor of history and government and the author of History’s Greatest Libels. He can be reached at [email protected]

Correction: As originally published, the article incorrectly stated that the three words underneath the FBI logo on the door were: “Liberty, Bravery, Integrity.” They are: “Fidelity, Bravery, Integrity.”