Just in time for the kick-off of the electoral season comes a movie that reminds Americans yet again what is wrong with the government we have endured for the past eight years. The riveting 13 Hours: The Secret Soldiers of Benghazi, directed by big budget action film director Michael Bay and based on the nonfiction book 13 Hours by Mitchell Zuckoff, is a soldier’s-eye view of the notorious terrorist assaults on two American compounds in Benghazi, Libya, on September 11, 2012. The movie is not for all tastes, featuring combat violence aplenty (though no gratuitous gore) and an excess of R-rated language. But it is political storytelling at its best — precisely because it tries very hard to be subtle. There are no overt references to Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton, for example, even as the frustrating paralysis of official government channels puts lives in danger. But the viewer is left in no doubt as to who the worst villain is: not the battalions of Libyan terrorists, but the government functionaries unable and unwilling to make the hard decisions.

We all know how the story ends: on September 11, 2012, four Americans, including U.S. Ambassador to Libya Chris Stevens, lost their lives, and the political finger-pointing continues. 13 Hours shows us how events unfolded, based on eyewitness accounts. The story centers on six security consultants charged with beefing up the defenses of a secret CIA compound in Benghazi whose very existence is unknown even to high-ranking officials in the U.S. government and military. As former Special Forces and combat veterans, they are unaccustomed to the cautious, bureaucratic ways of the CIA.

The station chief, played ably by David Costabile (of Breaking Bad fame), is mostly concerned with finishing up his tour of duty in Benghazi incident-free and with keeping intact the chain of command at any cost. Even when the diplomatic compound is attacked, with the flames and gunfire visible in the distance and personnel there pleading for help over the radio, Costabile’s nameless CIA chief stands firm, preventing the six security contractors from going to their aid — because he has not received authorization from his superiors, and because he fears what might happen if the six get themselves killed.

Eventually, of course, the six defy his orders, only to find the compound already burning and most of the perpetrators fled. Correctly anticipating that the “secret” CIA compound will be the next target, they make their way back across town to defend the American personnel trapped there, in an epic, three-part gun battle that lasts until dawn.

There are, to be sure, deft references to the indecision and venality that characterized the Obama Administration’s handling of the Benghazi attacks from the beginning. There is, for example, the moment when one of the heroes informs the others that Americans back home are being told it was a protest against an anti-Muslim film, which they scoff at. There are the moments when the Americans under siege learn — to their disbelief — that the United States has no military assets close enough to give them air support or mount a rescue operation. And there is the constant bureaucratic paralysis that apparently prevents even an overflight of F-16s — a show of strength from Aviano Air Base that the trapped Americans in Benghazi beg for but do not get.

There are also moral doubts expressed by members of the team of security contractors, that the entire Libyan military adventure is ill-advised, that they will end up dying in a foreign land for a cause that is clear to nobody.

This, of course, is the most important lesson to be garnered from the Benghazi debacle — the same lesson that should have been learned in Vietnam, in Mogadishu, and in Iraq, among many other places: there is no moral basis for empire building and military interventionism. The late Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi was an awful tyrant, to be sure — one of many dragons the U.S. armed forces have been sent abroad to slay — but he was Libya’s problem, not ours. The same could be said of Iraq’s Saddam Hussein and Syria’s Basher al-Assad, but the lesson appears to fall on deaf ears among policymakers in Washington time and again.

The Benghazi attacks have gained especial notoriety because of their timing (the crucial final sprint of the 2012 presidential campaign) and the Obama administration’s consequent attempts to downplay its significance and cover up what actually happened. Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney, for all his considerable deficiencies, was one of the first to publicly call the attacks terrorism — and was roundly ridiculed by the Obama administration and their media lackeys. Not until Obama was safely re-elected did the official narrative of Benghazi change, and Michael Bay’s treatment of the incident leaves no doubt about what actually happened.

Nowhere is there any evidence of an anti-American demonstration. Instead, we see shady-looking groups of Libyans skulking around the two American compounds, taking pictures and carrying out surveillance. Police cars and other vehicles drive up periodically, only to speed away, and supposedly trustworthy Libyan security personnel at the diplomatic compound take pictures of the facility and make suspicious phone calls. When the attacks come, they are well-coordinated, carried out by heavily armed men with the help of sympathetic locals.

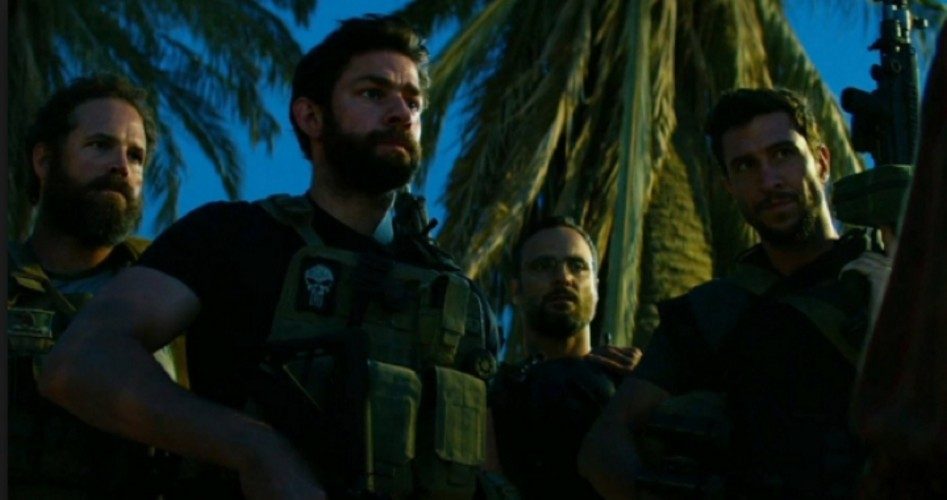

This is not a movie about warm and sympathetic characters and their complex interpersonal relationships. Most of the dialogue is macho banter and military order-barking, as befits the subject matter. But 13 Hours does show video footage of some of the men’s families. The actors portraying the six contractors deliver their lines crisply, without a hint of schlock, although the presence of John Krasinski and David Denman playing comrades-in-arms is likely to provoke cognitive dissonance among fans of the TV comedy series The Office.

In the end, the movie avoids the tedious sermonizing so typical of Hollywood political thrillers, preferring to tell the story as close to the book as it can and trust the viewer to draw his own conclusions. It is impossible for any rational viewer not to feel empathy for the four men killed so needlessly in Benghazi, nor disgust for the calculated political gamesmanship that led up to this debacle.

While the movie occasionally traffics in excessive Arab stereotypes (almost everyone in Benghazi is untrustworthy and prone to hair-trigger violence, apparently, as shown by the tense street confrontation at the beginning of the film and in many other non-combat situations), it also makes clear that huge numbers of Libyans were appalled by the Benghazi attacks and demonstrated by the tens of thousands in anger and shame at the death of the hugely popular American ambassador, who spoke Arabic fluently and was in North Africa for many years.

Whether 13 Hours will provoke renewed interest in Hillary Clinton’s role in the Benghazi affair is yet to be seen. But it is a spare, worthwhile portrayal of selfless American military virtue at its best, and should take its place among the best films (so far) to foray into the vexed politics and nuanced morality of America’s post-9-11 wars and entanglements.

Related articles:

Clinton Exposed as Liar in Benghazigate Hearings, but Secrets Remain

Will New Benghazi Probe Answer Real Questions?

Amid Political Posturing, Real Benghazi Scandals Ignored

Clinton Testimony on Benghazi Leaves Real Questions Unanswered

Benghazi Report Ignores WH Lies, Obama Gunrunning to Jihadists