The fiasco of Rolling Stone magazine’s apology for an unsubstantiated claim of gang rape at a University of Virginia fraternity house — and the instant rush to judgment of the university administration in shutting down all fraternities, when those charges were made — should warn us about the dangers of having serious legal issues dealt with by institutions with no qualifications for that role.

Rape is a crime. It belongs in a criminal justice courtroom. And those found guilty belong behind bars for a long time.

What could possibly have led anyone to believe that college professors or campus administrators should be the ones making decisions about charges of criminal acts that can ruin the lives of the accuser or the accused?

Many years ago, the late William F. Buckley said that he would rather be ruled by people with the first hundred names in the Boston phone book than by a hundred Harvard professors. Having spent more than half a century on academic campuses across the country, I would likewise rather have my fate decided by a hundred Americans chosen at random than by a hundred academics.

Have we forgotten the charges of gang rape against members of the Duke lacrosse team in 2006 — and how quickly the lynch mob mentality swept across the campus, before there was a speck of evidence to indicate whether the young men were either guilty or innocent?

Do we want people punished, based on other people’s preconceptions, rather than on the facts of the individual case? Apparently there are ranting mobs who do, and many in the media who give them a platform for spouting off, in exchange for the mobs’ providing them with footage that can attract an audience.

The law is not the place for amateurs. We do not need legal issues to be determined by academics, the media or mobs in the streets.

Every society has orders and rules, but not every society has the rule of law — “a government of laws and not of men.” Nor was it easy to achieve even an approximation of the rule of law. It took centuries of struggle — and lives risked and sacrificed — to achieve it in those countries which have some approximation of it today.

To just throw all of that overboard because of mobs, the media or racial demagoguery is staggering.

A generation that jumps to conclusions on the basis of its own emotions, or succumbs to the passions or rhetoric of others, deserves to lose the freedom that depends on the rule of law. Unfortunately, what they say and what they do can lose everyone’s freedom, including the freedom of generations yet unborn.

If grand juries are supposed to vote on the basis of what mobs want, instead of on the basis of the evidence that they see — and which the mob doesn’t even want to see — then we forfeit the rule of law and our freedom that depends on it.

If people who are told that they are under arrest, and who refuse to come with the police, cannot be forcibly taken into custody, then we do not have the rule of law, when the law itself is downgraded to suggestions that no one has the power to enforce.

For people who have never tried to take into custody someone resisting arrest, to sit back in the safety and comfort of their homes or offices and second-guess people who face the dangers inherent in that process — dangers for both the police and the person under arrest — is yet another example of the irresponsible self-indulgences of our time.

Force cannot be measured out by the teaspoon, and there are going to be incalculable risks every time force is resorted to, because no one can predict what is going to happen in the next moment. Anyone involved can end up in the hospital or the morgue. Let the responsibility lie with whoever forces a resort to force.

When it comes to dealing with mobs, the idea that the police should not show up in riot gear, or with anti-riot equipment that looks menacing or “military” — lest this “inflame” the mob — is an idea that might have seemed plausible to some in 1960. But we have had more than half a century of experience to the contrary since then.

The “kinder and gentler” approach was used in Detroit during its 1967 ghetto riots. More people died in those riots than in any other 1960s riots, the great majority of the dead being black.

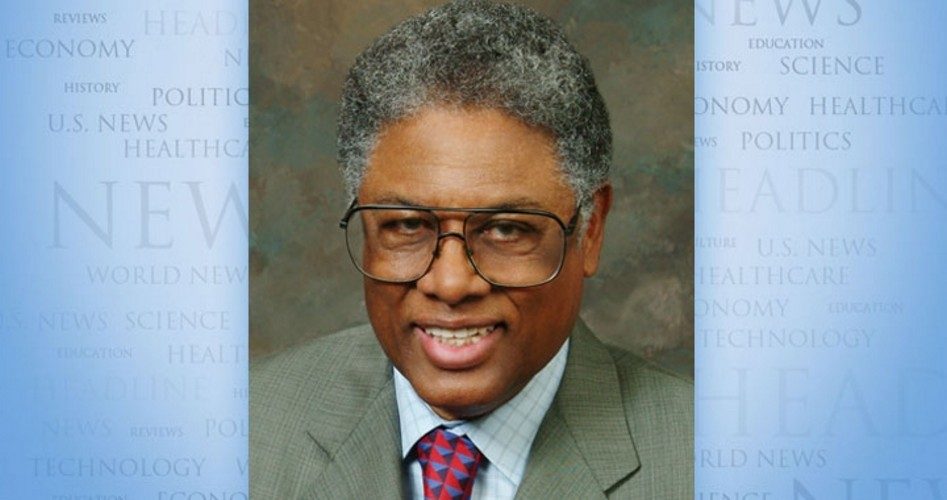

Thomas Sowell is a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305. His website is www.tsowell.com. To find out more about Thomas Sowell and read features by other Creators Syndicate columnists and cartoonists, visit the Creators Syndicate Web page at www.creators.com.

COPYRIGHT 2014 CREATORS.COM